Translated from the Tamil by Aniruddhan Vasudevan

Translated from the Tamil by Aniruddhan Vasudevan

Published by Pushkin Press 25 July 2019

288pp, paperback, £9.99

Reviewed by Elizabeth Hilliard Selka

Here’s the question. What justification could there be for a woman in a traditional, close-knit 1940s rural community ruled by patriarchy and superstition, who loves her husband and family and is loved by them, to make a decision to go out and sleep with another man, someone she doesn’t know, for a one night stand? What could possibly be her motivation, and for what possible reasons could (some of) her family support her decision and facilitate her action? And then, were she to act thus, what consequences would follow?

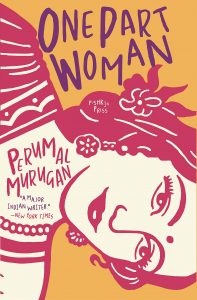

One Part Woman is an acclaimed novel by Perumal Murugan, written in Tamil and available now in an American-English translation by Aniruddhan Vasudevan, that tells exactly this tale while tenderly exploring one couple’s loving relationship and its limits. The novel has won various awards and even the translation was nominated for a National Book Award. Murugan himself is from a family of farmers in Kongunadu and is now an established author and academic: he has written ten novels as well as short stories, poetry and non-fiction, and is a professor of Tamil. One Part Woman is written in deceptively gentle, flowing prose, but this ‘quiet’ novel by a respectable writer became the focus of violent protest by caste-based and religious Hindu groups. Following a shocking hate campaign by members of the Kongu community in Tamil Nadu—copies were burned and the author subjected to death threats—Murugan was forced by the local police to sign an apology and the district government banned the book (a ban subsequently overturned by the Chennai High Court). At the time, he wrote on his Facebook page: ‘Perumal Murugan the writer is dead.’ This furore puts one in mind of The Satanic Verses, except that this is a scandal of which we in the West were ignorant at the time.

Back to the plot. Kali and Ponna are husband and wife; Kali adores his wife and her body, and the couple look forward to having children to crown their love and create a family. Only it doesn’t happen – Ponna does not become pregnant and consequently suffers stigma and humiliation from members of the community, though not generally from Kali except when he cruelly teases her that he’ll have to acquire another wife. They try everything, performing every traditional and religious rite available to them in order to appease their gods and make a baby happen. Aspersions are cast on Kali’s manliness and feisty Ponna is tortured by her barren state—those of us who either procreate with ease and fecundity or don’t want children do well not to underestimate the bitter anguish of the unwilling childless in any society, especially one in which your perceived purpose in life is to provide the next generation and where clinical medical resources are unavailable. Desperation feeds superstition; then a radical possible solution emerges in the form of the fictional local chariot festival. This event celebrates a half-female, half-male god Maadhorubaagan (hence the novel’s title, One Part Woman); on the eighteenth night of the festival the conventional mores of marriage are suspended to allow consensual sexual relations between all men and women on the basis that the men are become gods for those hours.

Kali and Ponna have now been married a dozen years. As the festival approaches, they consider and reject taking advantage of the licence offered by the conventions of the eighteenth night, but Ponna’s family decide otherwise and manipulate events accordingly. What does Ponna herself want, and what is she to do? If she accedes to their plans, is she prostituting herself or is she empowered, bravely taking back control of her own body, owning such superstitious practice and bestowing herself where and how she sees fit in order to achieve her own ends? If so, how will she select a male from the mass of people present? Will Kali prevent her or be kept in ignorance, and if initially the latter, will he eventually discover what has happened and how will he react? And if she does accede, will the longed-for pregnancy result? These are the questions which ramp up the tension as the narrative gathers pace and unfolds towards its conclusion, and not all are necessarily answered.

In 2015 the Indian Languages Festival gave One Part Woman the Samanvay Basha Samman Award after considering books written in five different Indian languages. In his heartfelt appreciation the chairman of the judges wrote about the novel’s ‘honest exploration of the tyranny of caste and the pathology of a community. [It] dreams of a secular future for communities in India that remain hostage to the ways of the past…’ The festival director added that Murugan’s ‘insider-outsider act of writing could serve the society and connect its histories with its contemporary realities and dreams.’ This is an intriguing, challenging novel and one which it is no trial to read for oneself, and judge.