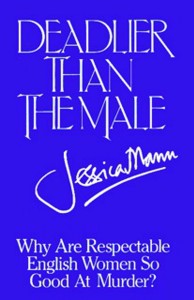

An Investigation Into Feminine Crime Writing

An Investigation Into Feminine Crime Writing

Available as an ebook, approx 246 pp, £1.99

The golden age of crime fiction was dominated by women writers such as Dorothy L. Sayers and Agatha Christie who took this genre to the heights and kept it there.Although that age is eclipsed, and its social norms now antiquated, the novels endure. What is it about these women’s work that has kept it alive? And what was it about the authors that gave them such violent or cunning imaginations, always hidden behind the most respectable of facades? In this book, first published in 1981, writer and reviewer Jessica Mann brings the perception of a fellow crime writer to her investigation of her predecessors’ lives and work. She discusses the changes in the mystery form over the years, and its enduring worldwide popularity, in a book that was described by one critic as ‘obligatory reading for any reader of crime fiction’.

Below, Jessica Mann introduces her perceptive study of crime writing from a female point-of-view. For crime fans of all stripe, the following – and of course the book itself – make fascinating reading.

*

When I was commissioned to write this book, in 1979, I bought all the other publications about crime fiction that I could find. They took up one shelf of a book case. There was Julian Symons’ Bloody Murder, a masterly study even if I did disagree with almost all his likes and dislikes; H.R.F. Keating had published several commercial books on the subject; there was Howard Haycraft’s Murder for Pleasure and Barzun and Taylor’s Catalogue of Crime; there were interesting prefaces such as a Dorothy L Sayers’ musing on detective fiction in her introduction to a book of short stories. But the subject was not recognized as a serious one by those who were serious about English literature, a category in which crime novels were definitely not included.

In the years since then, crime fiction has come in from the cold. It is studied at universities and reviewed with more respect than in the past, and has become an accepted if not very much respected form. So far (writing this in 2014), no crime novel has yet reached the shortlist of the Man Booker or any other serious prize for fiction.

The prestige of crime fiction having changed, an ever increasing number of books, articles and academic studies have been written on the subject. My single shelf has, in the intervening decades, expanded into a whole bookcase full, and that is an edited collection. It would be easy to fill several more.

The subject interests me not only because I’m a crime writer myself but also because I am and have always been a crime reader – and have always been asked by those who are not, why I spend (“waste”) my time reading crime fiction – a question that has never had an easy answer. These days, as the crime fiction reviewer for the Literary Review, I am bombarded with new crime fiction, on average three to four dozen books a month. But I am still unable to explain to myself or anybody else why some of these books are what I actually want to read, and to write.

Writing about them had not been my idea. I had done some reviewing, and published seven crime novels, when the subject of this book was suggested to me. The West Country publishers, David and Charles, who specialized in non-fiction about local history and transport and so on, had taken on a new editor whose brief was to expand their list into other subjects. Whether it was he who thought of it or whether my then agent had the idea and sold to him and then to me, I don’t know, because after the contract was signed and before the book was finished this editor left David and Charles. He wasn’t replaced and the firm reverted to concentrating on its original interests, which was bad luck on me and the author in a similar position whom I had met, and on at least three more whose names and books are advertised on the dust jacket of mine. Not surprisingly, without an editor interested in pushing them, none of these books became good let alone best sellers. And in the case of Deadlier Than the Male, quite a lot of it was quite soon overtaken by events, those events being the publication of material that showed details and information that hadn’t been available to me when I was writing and would have changed my opinions in several cases.

For example, writing about Dorothy L Sayers I had plenty of material to draw on about her books but not so much about her life. James Brabazon was working on an authorized biography at the same time but his interest was in Sayers as a lay theologian. Janet Hitchman had published her scandal-revealing Such a Strange Lady but she was more interested in the so-called strange and scandalous secret life than in Sayers’ writing. The revealing letters, published in five fat volumes and edited by Sayers’ friend Barbara Reynolds didn’t appear until much later.

Apart from ‘The Big Four’ – Dorothy L. Sayers, Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh – I mentioned several other writers about whom I found out what I could. It was usually rather limited information but since then nearly all have been the subject of carefully researched biographies, in fact in most cases more than one. The upshot of all this is that some chapters in my book reflect what was known 30 years ago and also, I think, reflect what these authors would have wanted the public to know. Later revelations have changed my, and everyone’s, opinion of these women, but in fact, if they chose to present a false face to the world, that is in itself interesting and says a good deal about the nature of ‘golden age’ crime writers and the society that they lived in.

In the twenty-first century, respectability has become an old-fashioned if not obsolete quality. It does not shock us in the least that Dorothy L. Sayers had an illegitimate son or that Agatha Christie had been divorced. It’s important to remember that both these facts would have appalled their contemporaries and did in fact shock these women themselves – they were actually ashamed of what they had done. For it was not until at least the 1970s that the old order began to weaken, and the accepted customs of British society changed so dramatically. Golden age detective fiction described and grew out of a society with rigid rules of behaviour. Sex before marriage, adultery, children born out of wedlock, homosexuality – all were shocking transgressions, quite unacceptable to respectable people. There was a ‘colour bar’ in Britain until late in the twentieth century, anti-Semitism was endemic in a regulated society, and such things were freely and openly discussed.

In this context, the point about all these and other time-expired embarrassments is that they made plausible motives for murder.

Obviously changed principles and customs are the most noticeable sign that classic crime fiction comes from a different era, but the changes in our material culture have also been enormous.

It may not be a very long time before classics of detective fiction will have to be published with footnotes to explain the obsolete oddities of normal behaviour, though it will be necessary for readers to know of them in order to understand what’s going on.

At a more trivial and material level crime fiction is a reminder of small changes and details that are ignored by serious scholars, but manna for some social historians. Think of the men taking their cigarettes from a special cigarette case, tapping the end on a hard surface, fitting it into a tortoiseshell holder – a small detail of normal behaviour, now forgotten. What will the antiques shows of the future make of these neat little containers or the short pipe? A trivial example, but it’s the trivia of daily life that furnish traditional detective stories, so it seems likely that the classics of crime fiction will still be consulted if only for the information derived from them. Whether the books will still be read for pleasure is another question, for contemporary tastes are so very different. Candour, plain speaking and lack of polite concealment have become so much part of our lives that the polite periphrases of a more mealy-mouthed age can seem irritating. It is very difficult to imagine the reverse: what would readers, or writers, of the inhibited past have made of the determinedly explicit descriptions of violent death and adventurous sex that characterize twenty-firstt century crime novels? For realism has become the watchword.

If detailed descriptions of all physical experiences – sex, wounding, violent death – is all that a novel needs to count as realistic, then fair enough. Otherwise my own view is that more precise accounts of what happens to the human body when wounded, or during sexual encounters, do not in themselves make crime fiction more factual. Realism about murder would require recognition of the fact that 99.99% of murders in Britain are domestic, unplanned, and within the family; and that the same proportion of murderers are people (usually male) at the very bottom of contemporary society.

Equally distant from real life are the numerous television series purporting to be realistic descriptions of police procedures (which is probably true) and of police officers – which has to be nonsense. How different contemporary society would be if police officers were really as perceptive, imaginative and altruistic as they are in crime fiction. As for the series of novels featuring infinitely inventive sadists and their wretched victims (always girls or women) they stretch credulity to breaking point, but are still immensely profitable to author and publisher alike.

The fact to remember is that public tastes change, and so do authors’ imaginations. Women, whose earlier books featured torture scenes, have children and find they can’t bear to imagine such inventive cruelty any more. So a new sub-group of crime novels develops, featuring babies or young children in peril as the new mother tries to tame her irrational fears by turning them into stories.

We don’t yet know whether these contemporary novels, so much more emotional than the traditional detective story, are still ‘the normal recreation of noble minds’ as a mid-twentieth-century critic put it. When such readers as President Roosevelt and the philosopher Bertrand Russell claimed them as favourite reading, they were talking about the crime novel as puzzle, something that involved the reader’s brain without troubling his or her emotions. A few such books are still written, but it is unusual now for crime fiction to be so abstract. The overlap with mainstream fiction is quite substantial, though crime fiction, takes many forms. Under its umbrella can be found historicals, supernaturals, police procedurals, social commentaries, comedies, science fiction and in fact any genre of invented tale. Statistics show that about one third of these books are by women.

Which of them will survive is as unpredictable now as ever. But I think it is safe to predict that crime novels and thrillers will remain popular reading and that women writers will still be ‘so good at crime’.

*

Introduction to the 1981 edition

‘The rise of the feminine author in the field of detective fiction may well serve some future scholar as the subject of a learned thesis,’ wrote Howard Haycraft in his pioneer study of crime novels.

This volume is not the learned thesis he envisaged, but an attempt to answer, at a less exalted level, the question, ‘Why is it that respectable English women are so good at murder?’ In an article about Dorothy L. Sayers, P. D. James, herself a respectable English woman who is extremely good at murder, said that this enquiry is one to which any female writer of mysteries is accustomed, particularly from American readers. The ambiguous wording of the question refers not to practitioners of real-life murder, but to those writers collectively described by authorities on the crime novel as ‘Grandes Dames of Detective Fiction’, or as a ‘Quartet of Muses’, or else as ‘The Big Four’: Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham and Ngaio Marsh. To these, most readers would add the excellent, though less prolific, Josephine Tey.

It is remarkable that the novels of these writers should have survived as popular reading, some for half a century, when the work of so few of their contemporaries has done so. In 1938, Cyril Connolly wrote: ‘I have one ambition—to write a book which will hold good for ten years afterwards . . . contemporary books do not keep. The quality in them which makes for their success is the first to go. They turn overnight.’

Connolly then described English literature a decade earlier, in 1928. He listed Lawrence, Huxley, Moore, Joyce and Yeats, Virginia Woolf and Lytton Strachey. ‘If clever,’ he said, ‘we would add Eliot, Wyndham Lewis, Firbank, Norman Douglas, and if solid, Maugham, Bennett, Shaw, Wells, Galsworthy, Kipling.’ By 1938, Connolly could say that the reputation of most of these writers had declined. Of the eminent writers of ten years before, ‘only the fame of Eliot, Yeats, Maugham and Forster has increased’.

Half a century on, literate people will admire a few of the authors on Connolly’s list, will have read the works of several, and probably heard of all. Some of the writers have become cult figures, others quarries for an academic’s excavation. Most of their works will be available in libraries, or in editions published as ‘modern classics’ or as students’ texts.

Connolly left out books which have remained popular with non-specialists. Authorities on literature will take his omissions for granted, but to a general reader it must be noticeable that none of the popular authors whose work has been continuously available in print, in hard and soft covers, in general and specialist bookshops and on the shelves of current fiction in the public libraries, is included. Survival in commercial terms seems to be something of which ‘genre’ fiction is especially capable. Comedies, such as the works of P. G. Wodehouse and Nancy Mitford, adventure thrillers with their continuously rejuvenated heroes, romantic novels, so unchanging in form and outlook that they can be reprinted word for word except for updated details of clothing, and historical novels, like those by Georgette Heyer and C. S. Forester, can be very long lived. All share with the conventional detective novel a lack of serious purpose; most show a class consciousness which has rendered light fiction odious to many commentators. In each category, a few writers found a style that still entertains readers of a later generation.

The period between World Wars I and II is sometimes called ‘The Golden Age of Detective Fiction’ and vast numbers of mystery novels were published during those years. A type of book at one time regarded as a deplorable aberration, they are now the object of collectors’ attention and the subject of scholarship. But today few of the names of their writers are familiar to any but an educated enthusiast. In 1939 Dorothy L. Sayers published an article in Illustrated Magazine called ‘Other People’s Great Detectives’. She concluded it:

Dr. Priestley, Dr. Gideon Fell, Bobby Owen, Asey Mayo, Philo Vance, Roger Sheringham, Max Carrados, Hanaud, Charlie Chan, Mr. Pinkerton, Inspector Poole, Sir George Bull, Albert Campion, Colonel Gore, Sir Clinton Driffield, Superintendent Wilson, Miles Bredon, Sir Henry Merrivale, Dr. Eustace Hailey, Drury Lane . . . which, if any, would you back for the immortality stakes—fifty years on the level, with a fair field and no favour?

I do not think that Dorothy L. Sayers herself or any of her readers, to whom all these names were probably well known, would have guessed that so many of her runners would fail to reach the finishing post. For we are now at the last hurdle, nine years to go at the time of writing, and as far as I can tell, Albert Campion is the only one of her runners still in the field; some people might include Gideon Fell and Sir Henry Merrivale, but a survey of the books available on most paperback counters would not support them. And Sayers left out names which would have been worth betting on: Wimsey, Alleyn, Poirot and Grant. What gave them, out of so many, such stamina?

Only ten years before Sayers wrote those words it was possible for an American professor, herself both knowledgeable and enthusiastic about detective novels, to remark that, ‘The detective story is primarily a man’s novel . . . and . . . the great bulk of our detective stories today are being written by men.’ (Marjorie Nicolson, in Atlantic Monthly.)

Anybody knowledgeable and enthusiastic about detective novels today, asked to name British authors whose work has survived since the Golden Age would probably, after Conan Doyle, mention Christie, Sayers, Marsh and Allingham.

It is with a certain unease that a lifelong feminist recognizes any but the most objective differences between men and women writers. Since fame and fortune have come equally to writers of both sexes, in this sphere at least there should be no qualitative distinction. Is it merely a coincidence that in this century the most successful British detective novelists have been women? One cannot, after all, postulate statistical trends from such small samples. Yet there were many men writing crime novels at the same time as these women, men who were thought by their contemporaries to be equally skilled and whose books were equally popular.

Arnold Bennett was the Evening Standard’s chief book reviewer between 1926 and 1931 and covered an impressive range of topics with good and just judgement. He praised mystery writers who are now quite forgotten, such as D. Maynard Smith and Bruce Graeme. He was told by an ‘independent and erudite student of detective fiction’ that a book by J. J. Conington (The Case with Nine Solutions) was representative and among the best of the school. Who remembers it now? Other enthusiasts regarded John Rhode, Henry Wade and numerous other masculine authors as far superior to Sayers or Christie; Bennett said that he could not force himself ever to finish reading the latter’s novels. There are indeed male crime novelists whose work has survived, in print at least, but none has the same popular esteem. In America, the best, and best known, crime writers have been men, and it is their work which the general reader still enjoys, the books of the ‘hard-boiled’ school of writers such as Spillane, Hammett and Chandler. British men of a slightly later generation have written among the best crime novels ever published, for instance, Michael Innes and Nicholas Blake (C. Day Lewis), but in discussing the original question with several authorities on the subject of crime fiction, I have met with no disagreement on the fact that four or five women represent the most popular writers from the Golden Age of Detective Fiction.

There is considerable disagreement as to the reasons. One contemporary reviewer supposed that men were not writing that kind of book then. Another believed that women were not writing any other kind of book, as he had not heard of the numerous excellent writers like Margaret Kennedy, E. M. Delafield, Angela Thirkell and Storm Jameson, to mention only a few, whose sensitive and literate novels are out of fashion now. A successful thriller writer of the 1970s attributed a book’s life to publishers’ policy, insisting that the capricious nature of ‘blacklists’ had little to do with merit. What it has much to do with, however, is popularity; publishers offer what they believe will sell, and books which are not bought are not reprinted. Whatever the reason, the public, not only in Britain and the United States, but in most countries of the world, bought and still buy the novels these women wrote.

So I return to the question: why is it that respectable English women are so good at murder? Inherent in this question are several others. Are English women better at writing about murder than those of other nationalities? Maybe not; but they are certainly more popular. Even Mary Roberts Rinehart, who would be claimed by many American readers as their answer to Agatha Christie, is little known outside the United States, Are English women better at this work than English men? The answer must be, if success and survival are the criteria that they are. Are they respectable? I shall show that these famous women crime novelists were conventional, conformist and conservative, and that their very adherence to accepted standards in their fantasies made the product of their imaginations attractive to the public. Is murder their preferred subject? Josephine Tey, after all, had her greatest successes with novels about other crimes. Nevertheless, the plot and structure necessary for a murder mystery, and the moral certainties involved in its elucidation, seem to be among the ingredients for success, while the personal reticence the form allows, the barrier which the author can erect between herself and her readers, is apparently desirable for both these readers and these writers. They eschew self-revelation, they dislike the verbal strip-tease of more emotional fiction. Above all, is crime a subject which any self-respecting reader or writer could or should prefer?