Translated by Margita Gailitis

Translated by Margita Gailitis

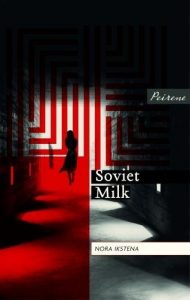

Published by Peirene Press March 2018

196pp, paperback, £12.00

Reviewed by Rachel Hore

Nora Ikstena’s first novel was published in 1998 and she has written over twenty books since. Soviet Milk is her most recent, and won the 2015 Annual Latvian Literature Award for Best Prose. Set between 1969 and 1989, the novel is narrated alternately by a mother and daughter who both grow up in a Latvia under Soviet rule.

The mother (neither of the main characters is given a name) was born in war-shattered Riga in 1944, but shortly afterwards her father was beaten up by the soldiers plundering his crops and taken away, leaving his wife and baby to fend for themselves. Though in due course acquiring a loving stepfather, she grows up a strange, lonely, isolated child, who becomes consumed by her ambition to study medicine. Against all odds she succeeds. On the way, a one-night stand after a dance results in the birth of a daughter of her own, but she’s so traumatized she cannot bear even to breastfeed her. The grandmother and step-grandfather help bring up the little girl.

Although the oppression of life under Communism infuses this tender tale, Soviet Milk is principally a story about individual character, not politics. There’s no doubt that the mother is a wounded soul, who struggles and fails to be happy, but the author offers no pat answers about why. She is so delicately and warmly evoked, however, that the reader is stirred to empathy rather than impatience.

The woman’s promising career as a gynaecologist is destroyed by a single, small, impulsive act of resistance, for which the authorities condemn her to mundane work in a far-off rural clinic. Here, her little daughter joins her and they muddle along together, the child sometimes the carer, sometimes returning to her grandparents in the city when occasion demands. The mother is ground down by her work, but the simple countrywomen who consult her about their pregnancies adore her. So does the blurred-gender Jesse, to whom she’s kind but whom the rest of the community regards as a freak. The gynaecologist loves her own mother and her stepfather yet cannot bear to be with them. These complexities are carefully portrayed.

The young girl’s narrative is delicately written, too, but where her mother is sad, her spirit is usually full of joy. The loving relationship between them and the girl’s with the grandparents are intricately depicted as the girl grows up, clever and full of integrity.

Jesse tells the girl at one low point: ‘This is the hand we’ve been dealt. We’re worn out from carrying heavy burdens. Everything has to be accepted with humility… Then you’ll regain your strength of soul.’ Soviet Milk is a story of ordinary people who are actually extraordinary and that gives it a universal appeal. Despite its elegiac tone, it’s ultimately upbeat because of the sense the writer leaves us with that, despite the system they live under, which stifles what they say and do, their lives matter.