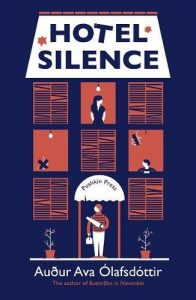

Published by Pushkin Press 22 February 2018

Published by Pushkin Press 22 February 2018

224pp, paperback, £9.99

Reviewed by Shirley Whiteside

Jonas is a middle-aged man in crisis; getting tattooed is just one sign of his malaise. The anchors of his life have come loose and he is not sure there is a reason to go on. His wife has divorced him, but not before telling him that his twenty-something daughter, Gudrun Waterlily, is not his biological child. His mother has dementia and is sliding into another world. Her lucid moments are becoming more and more rare, and Jonas misses the woman she was. He decides to end it all and calmly contemplates his options. He feels he can’t subject Gudrun Waterlily to the horror of finding his body and decides to disappear, choosing to travel to Hotel Silence, in an unidentified war-torn country, currently experiencing a lull in hostilities. He takes a toolbox and drill with him in case he decides to hang himself and needs to put up a hook.

Icelandic author Olafsdottir’s prose is pleasingly, engagingly spare as she allows things to be left unsaid between the various characters and in the narrative as a whole, leaving gaps that readers must fill in for themselves. Considering the initial subject matter – suicide – this novel is by no means a glum or depressing read. The author has gifted Jonas with a dry wit and an often funny, matter-of-fact attitude to ending his life.

Unexpectedly, Jonas finds life amongst people who have suffered great losses and hardship gives him a new perspective. Hotel Silence, run by brother and sister, Fifi and May, is rundown and in need of many small repairs. Toolbox in hand, Jonas starts to enjoy the feeling of being needed again as he fixes problems around the hotel. He befriends May, who has a young son, Adam, and feels he has a place in the world again. The locals, many of whom are physically and mentally scarred, make Jonas re-assess his life and his decision to end it. Whilst he feels cast adrift, these people have faced the ghastliness of war and yet they do not talk about the past, only their plans to rebuild their shattered lives. He also reads his student notebooks and rediscovers himself as a young man.

Hotel Silence (winner of the Icelandic Literature Prize) could easily become a run-of-the-mill story of one man’s search for redemption but Olafsdottir makes sure that there are no simplistic, happy endings for everyone. Jonas’s spiritual journey from depression to a kind of normality is echoed by the attempts of the locals living around Hotel Silence to return to their pre-war lives. A sense of hope for the future is present in the latter part of the novel, in contrast to the opening chapters. In Jonas, Olafsdottir has created a rounded, humorous character and it is a pleasure to spend some time in his company.