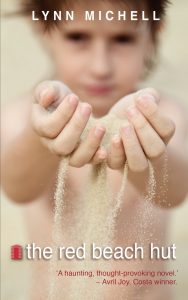

Published by Inspired Quill 3 October 2017

Published by Inspired Quill 3 October 2017

252 pp, paperback, £8.99

Reviewed by Alison Coles

The first paragraph of this novel gives you all the feel of the characters you need, to enter into the world inhabited by its two protagonists, Abbott and eight-year-old Neville. More information will come, and interaction will tell you more about them and their passage through the short time they spend on the beach, but the simple introduction – ‘The man and the boy stood hand in hand on the top concrete step and stared, like they always did, towards the line where the sky melted into the sea… it took a few minutes for the two of them to feel at ease with each other’ – comprehensively sets the tone of trust and intimacy.

Lynn Michell captures the gentleness and purity of both characters, and their innocent yearning for something to fill their separate emotional vacuums. So far so good – we have been privy to the pure side of their relationship, their intentions, but it is not long before we view how the world sees them, and labels them, and impugns the worst of motives to them. For this is the theme of the novel, it is about how the world leaps with speed to judge our outsides, our visible actions, through the lens of the powerful stereotype. It is about damnation without enquiry. It is about hypocrisy. It is also about our fears and the power they have over us.

The boy and the man both find themselves on this semi-deserted beach for different reasons. The man, Abbott, has a natural instinct for helping young troubled boys. In his career, he helps to straighten them up before they embark on a dedicated life on the wrong side of the law. But he has a secret, he is a homosexual and his credit card was once taken by a more daring partner who, for a few damaging seconds – without his permission or interest – wanted to view underage sex with boys. This is not Abbott’s predilection at all and he scrambles to erase any trace of what happened. His horror, fear and shame remain buried until an IT meltdown at work leads him to believe his secret is about to come out. In his panic, he flees, heads towards the precious beach hut his only aunt had left him in her will in order to hide away from those who might come after him. He imagines the worst.

Neville finds himself on the beach most evenings as his single mother needs him to be out of the house for a couple of hours while her paying customers, men, come to her for sex. He is to walk the beach, speak to no-one, buy a bag of chips and be back by 6.15pm. Neville counts everything – railings, the stars, the steps to the beach hut, chips – as a way of creating safety in his unsafe world. ‘I like to know, to check, how many stars make up Orion.’

Neville approaches Abbott, not the other way round. Abbott doesn’t want anything to do with anyone, let alone a small boy who might reveal his whereabouts, and rejects the boy’s friendliness.

Enter the villains of the piece, the Daily Mail-reading, newly-retired couple Bill and Ida, who take stock of other people’s business as they have little of interest in their own. (There is also a dig at biased, aged Guardian readers.) Lynn Michell confounds our own stereotypical understanding of the nosy parker, having the husband as the main culprit, not the wife. He has already reported Neville’s mother, Sharon, to the authorities who – as she worked with her friend Janie in order to protect each other – classed the home as a brothel and cast Janie out. The man knows who Neville is and watches as he meets Abbott, goes for walks along the beach with him, goes out in a boat with him – and goes to the hut to dry out his wet clothes. It is the boat trip that awakens Neville’s passion for something beyond his fear-driven limited life. ‘ “I’m already used to her (the boat). I love her.” It was heartfelt. Even passionate.’ After the trip, the climax comes in two ways: Bill’s call to the police and Abbott’s colleague Jim finding and reassuring him that his worst fears are unfounded. Nonetheless, Abbott and Neville’s short friendship is abruptly terminated by the police. True to his character, Abbott cares for the young boy’s wellbeing and later writes a letter promising to ‘come back, we can go for walks in the dark if your mum agrees and we can count the stars in Orion.’

By touching chords of such tenderness and insight, Lynn Michell positions the simple inside truths of these two characters way above the exterior actions of the ‘authorities’. Neville, on the last evening after the boat trip, has had his heart opened with this new experience – a non-swimmer, he trusted Abbott. ‘Neville spoke again, his voice was very quiet, the words almost whispered. “But I can wish… you were my dad.” ‘

It would be a shame if this book were not widely read, as it has a profound message for the way we live.