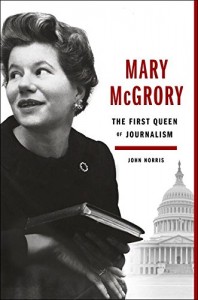

Published by Viking 22 September 2015

Published by Viking 22 September 2015

352 pp, hardcover, $28.95

Reviewed by Rachael Hanel

I studied journalism at university and then spent several years as a newspaper reporter in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but I’m embarrassed to admit I had never heard of Mary McGrory until I picked up John Norris’s biography of her.

I don’t know why her name never came up, but suspect it was because journalism programs tended to emphasize the men who succeeded in the profession. In school I learned about Walter Cronkite, Ben Bradlee, and Ernie Pyle. So when I read Norris’s book, I felt that I had uncovered a hidden gem. The trailblazing work of newswomen like McGrory, whose writing won her a Pulitzer, made it easier for other females, like me, to enter the journalism field.

McGrory worked in newspapers from 1942 until 2003, when she suffered a stroke at the age of 84. Her output was astounding: she covered twelve US presidential campaigns and produced more than 8,000 columns. She spent the majority of her career as a columnist for the Washington Star and when the Star folded, she moved to the Washington Post. Her columns, marked by sharp observations, poetic language, and solid reporting, were syndicated throughout the United States.

McGrory started in the newspaper business at a time when women had to choose either career or personal lif: cultural expectations made it difficult to achieve success in both. McGrory chose her career. Her job offered her unprecedented access to the nation’s most powerful leaders. While she grew frustrated over the closed doors she encountered because she was a woman, she used her gender to her advantage whenever possible. Presidents such as John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson trusted McGrory and often spoke to her at length and in confidence, which they didn’t always do with male reporters.

Norris offers readers a thorough account of McGrory’s long and successful life. This is a well-researched book, evidenced by the sizeable bibliography and exhaustive list of notes. He interviewed McGrory’s living relatives, close friends, and former colleagues to round out his portrait.

Norris doesn’t spend much time on McGrory’s personal life, likely because it is rather mysterious. While she did have relationships with men (including a long-standing on-and-off romance with fellow journalist Blair Clark), McGrory kept that part of her life fiercely private. She was concerned that as a woman, her personal life would be used against her in her career. Even family members and close friends did not know the extent of her relationships. Norris mentions a few paramours, and only briefly. His tendency to segue quickly from McGrory’s personal life to her professional life results in choppy reading at times.

I have never had to choose between career and family like McGrory, but too often I take that for granted. Norris’s biography gave me the chance to remember how recently it was that women were still making extraordinary sacrifices in order to have careers.