Published by Thames & Hudson 5 October 2015

Published by Thames & Hudson 5 October 2015

352pp, hardback, £39.95

Reviewed by Jessica Mann

Back in the dark ages, before the technological revolution, our house resounded to the clatter of keys, as, in my upstairs office, I typed crime fiction on an elegant, sage-green Olivetti, and downstairs, in his, my academic husband hammered out his learned books and articles on an Imperial typewriter, bought in 1958. Seduced by desirable technology, I must have upgraded a dozen times: electric typewriter, Amstrad, the first Windows computer and its numerous successors. But my enthusiasm for ever more sophisticated gadgets has not been infectious. The Imperial typewriter, its red body chipped and spotted with white-out, with a hole worn in the spacer bar and replacement ribbons hard to come by, is still in daily use and unexpectedly, after years of provoking mild derision, has become desirable as a gadget that can’t be hacked or cloned. And after looking through this huge and heavy book, people who have become accustomed to sophisticated electronics might well be tempted to have a go with the more primitive technology that produced such remarkable images.

The introduction begins with a little history, moving from the 1870s, when typewriters were first sold in large numbers, to the age of computers whose development brought to an end the manufacture of new typewriters, and then eventually on to the present day in which vintage machines are restored and re-used by enthusiasts. The authors suggest that, ‘The renaissance in vintage machinery may be analogous to the resurgence of Baroque music, with period instruments and baroque tuning now de rigueur.’ More simply, the actor Tom Hanks is not alone in saying, ‘I like to type.’

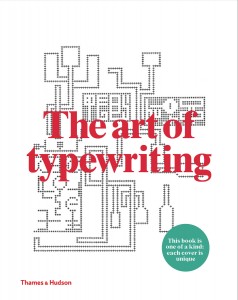

Doodling isn’t easy on a typewriter, but somewhere there will always be an energetic typist intent on transcending physical limitations. Typewriter art began as soon as typewriters were widely available in the late nineteenth century, the first published example a work by a British secretary called Flora Stacey. This art was only briefly spontaneous, for in the late 1930s ‘ornamental typewriting’, or art-typing, was formalized as a discipline when two books on the subject appeared. Then came Typed Prototypical Concrete Poetry, Visual Poetry and Typed artpoe – but by this time, the reader (at least, this reader) wants to move on from words to pictures. In nearly three hundred pages of reproductions, there are Textured Texts, Meandering Texts and Labyrinths, Love Poems and many other subdivisions of typewriter art. From pages that look like tapestry, to random patterns and squiggles, from houses built of letters to elaborate geometrical designs, and even the occasional portrait, one turns the pages marveling at the ingenuity and industry that made these images.

The authors, who started collecting typewriter art in the 1970s, now own tens of thousands of examples. Some of the pictures produced by the unlikely medium of a manual typewriter are ‘like a dog on its hind legs preaching’ – that is, remarkable only because they were difficult to make. But others – some abstract designs and patterns, a portrait or an arrangement of geometrical shapes – are really beautiful, a new (at least, new to me) art form.

Thanks for a beautiful review – you got it!