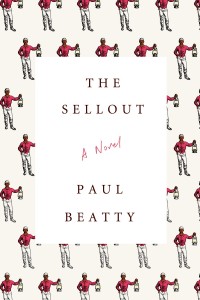

Published by OneWorld UK/ Farrar Straus & Giroux US

Published by OneWorld UK/ Farrar Straus & Giroux US

304pp

Reviewed by Elsbeth Lindner

Is there a town like Dickens? A contemporary, rundown black suburb of Los Angeles, it still supports an improbable slice of agricultural land worked by the novel’s central character and narrator (last name Me) who keeps livestock there, grows ambrosial fruit and vegetables, and stables a horse that he rides around the neighbourhood.

Me’s father, F.K. Me, was no farmer, however, but an esteemed African-American psychologist, author of the Theory of Quintessential Blackness and imposer on his son of controversial – and painful – racially-charged educational experiments. Unsurprisingly, F.K’s fate was to be gunned down by the local police force.

Now grown, the narrator has taken over his father’s local role as Nigger Whisperer (on call to talk down black members of the community close to breaking point) and has also made it his business to re-establish the Dickens township, recently wiped off the map by Californian authorities. Oh, and then there’s his thoroughly logical plan to re-introduce segregation into Dickens’s schools and buses, as a means of improving the lot of his fellow citizens.

Provocative is scarcely an adequate adjective to describe the devastating satire that is Beatty’s new novel, a work of such relentless imagination and thorough-going challenge to political correctness – and other cows, both sacred and non – that its pages fairly hum with energetic stimuli.

The end result of Me’s ambitions is his weed-fogged trial before the Supreme Court. The scenes from the courtroom, which open and close the novel, are themselves a riotous, scathing indictment of some black behaviours. In the intervening chapters, Me traces his life in Dickens from childhood to the present. By his side in recent years has been an older man, Hominy, the last living member of the Little Rascals, a film troupe that performed coon roles in an era of free and easy racism. Nowadays, Hominy is Me’s self-imposed slave, who addresses his boss as ‘massa’ and insists on weekly beatings which Me arranges via the costly help of a local dominatrix.

Beatty’s perverse comedy draws brilliantly on a fund of learning, observation and bright wit. Open it on any page for devastating puns, apercus, take downs of film, literature and American social history. Excoriating, profane, yet oddly uplifting and laugh-out-loud funny, this dazzling work of fiction stitches together provocations and insights on race that are of course deadly serious.

It’s a thrilling piece of work and its timing is as spot-on as the questions it poses.