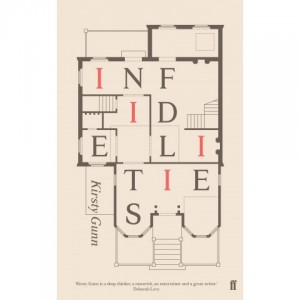

Published by Faber 6 November 2014

Published by Faber 6 November 2014

224pp, paperback, £10.99

Reviewed by Alison Burns

This new collection of stories by the award-winning author Kirsty Gunn is divided into three sections: ‘Going Out’, ‘Staying Out’ and ‘Never Coming Home’. In various ways (and various settings, from the Scottish Highlands to New Zealand), Gunn is exploring the inner lives of women. At the same time, she is examining narrative, and the nature of story.

Many of these tales highlight the loss of freedom in marriage, whether this comes from choosing or being chosen. In the first, a wife pursues a stranger barefoot into a wood, commenting on the wood’s ‘hundred little pathways’, to one of which she ‘walks straight in’; on her return, her young daughter mistakes the muddy mess in her mother’s bed for blood. In another story, an abandoned wife warms momentarily to an abandoned house eager to try out new owners. In ‘The Wolf on the Road’, a ‘ravenous’ wife swerves away from an affair (towards what exactly, is ambiguous).

This is a collection full of suggestive possibility, things flirted with. Language and form themselves are played with, notably in the vivid, economical story ‘Caravan’, which is told in reverse, beginning with activity and drama and dying down into a silence broken only by the elements; and also in ‘Scenario’, a clever story about the language of art and the language of feeling.

In the central section, four linked ‘Highland Stories’, one of Gunn’s other subjects is to the fore: secret knowledge, things seen, what she calls sightings. These four stories revolve around a sad, bewildered, angry boy called Bill, whose farming father is pushed ‘to the edge’ and over. Bill’s need makes him brutal, and it takes the sensitivity of his cousin Ailsa to see his suffering. Here, Gunn’s writing is strongly reminiscent of Alice Munro, reaching an impressive height in the final sentence of the sequence.

Another aspect of Gunn’s narrative prose worth noting is her imagery, which decorates her plain writing with grace notes. In ‘Elegy’, a dying woman decides to live in the moment; she experiences fleeting elation as like the flight of a bird, or the sound of a flute. In ‘Foxes’, an open-air opera performed on a fairytale bandstand has its lovers passing from one to the next, ‘the music like ribbons winding around them, binding them…to their fate.’

Throughout these stories, both the playful and the searing, Gunn is looking at the equal and opposite values of risk-taking and security (in writing as much as in life). This contrast is sharply reflected in two stories, ‘Tangi’ and ‘Dick’, neither of which is about wives. In the first of these, the daughter of a correct mother relaxes into the embrace of her expressive grandma’s home, where she can be sure of ‘all one kind of known and familiar life’ (a Munro-like phrase if ever there was one). In the second, a shattering tale of lost innocence, a man betrays his daughter, which is another version of infidelity.