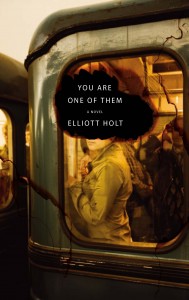

Published by Blackfriars 3 October 2013 (Kindle edition) UK, Penguin Press US

Published by Blackfriars 3 October 2013 (Kindle edition) UK, Penguin Press US

368KB, £3.99

Reviewed by Alison Coles

With the opening line – ‘The first defector was my sister’ – Elliot Holt sets a tone of unexplained loss, abandonment and secrecy, and maintains these tensions to the very last page. Set in the middle of the East/West hostilities of the 1980s, itself a canvas of fear and lies and imagined truths, this novel intertwines personal abandonment with national betrayal and the defection of loyal citizens.

The first third of the book is set in the USA and is told almost in diary form from the point of view of ten-year-old Sarah Zuckerman, a character inspired by Samantha Smith, an actual American girl who, at the age of ten, wrote a letter to Yuri Andropov in 1982, was invited to the USSR in 1983 and became a much celebrated child peace ambassador until her death in 1985.

Sarah Zuckerman has been conditioned by the early loss of her older sister Izzy. Sarah knows she has been abandoned and holds it in her cells, in her limbic memory, while powerlessly watching her parents handling their own loss. Sarah’s abandonment is compounded when her English father leaves – or, as she puts it, ‘defects’ – from the family back toEngland.

At age ten, still cleaving to the sense of family she no longer has, she makes a new best friend, Jenny Jones, and nestles inside this all-American perfect family living across the street. Sarah and Jenny do everything together. Meanwhile Sarah and her mother have managed their boundary-less insecurities by focussing instead on the world insecurity of imminent nuclear war. Her mother works for disarmament and Sarah, with Jenny, writes to Andropov in the USSR, imploring him not to start World War III. (Although this didn’t come to light until later, only Jenny’s letter gets sent.)

Jenny, pretty and photogenic, becomes a very famous poster girl for world peace, and is invited to Russia with her family on a much-publicized goodwill trip. Fame turns Jenny’s head and she abandons Sarah for another ‘best friend’.

This succession of losses impact on the little girl and she emotionally abandons herself, doubting herself at every turn. As she recalls with insight later on, ‘I had always been quick to assume I was in the wrong. My perpetual sense of wrongness followed me into clothing boutiques, where I apologized to the clerks who maniacally refolded the sweaters I picked up from display tables; to hair salons, where I was uncertain about how much to tip; to shoe stores, where I often bought the first pair I tried on….’

Then the news comes that the plane carrying the Jones family has crashed and they have all apparently perished. She has yet again been abandoned from the safe heart of the family. She still has a door key, though, and as she lets herself in and spends time in their house, what she learns sows the seeds of doubt as to whether all was as she had been led to believe. Later, as a college student, she is contacted by a Russian girl, Svetlana, who had apparently become a friend of Jenny’s on her Russian trip years before. Svetlana emails, ‘How do you know Jennifer Jones is dead? Because you saw on the television? You must also believe that your American cosmonauts walked on moon!’ This is Sarah’s axis: she empowers herself to go toMoscow and find the truth.

Holt’s depiction of the Moscow of this period is evocative of the bleakness, the despair, the unintentional comedy, the lack of supply of essential goods, the misery of the freezing temperature, the dead drunk with icicles dripping from his fingers and the girls who became willing ‘pillow dictionaries’ for their American boyfriends. And everywhere Sarah goes, she encounters deliberate duping and babushka-doll-like layers of lies.

It is during this time in Moscow that this wiser, older Sarah, by searching for the heart of her betrayal by searching for Jenny, finds her essential self. She learns gradually that she is not the sum of others’ actions, she is whole in herself; a seamless metaphor of going from the west to the east, the other half of the world, Sarah is going from one half of herself to the other.

This is a riveting read from start to finish. It would be very easy for such an inward, soul-searching book, written in the first person, to fall into dreary self-obsession, but the novel very much escapes that trap, partly because Sarah Zuckerman has a core of inner steel and undergoes a change in the relationship to her abandonment by the end of the book.

In the first part, we largely only hear Sarah’s voice and it reads like a child’s diary. Although this is necessary for us to form a picture of an inward-looking and damaged child, after a while it began to feel a little monotonous. But as we move into the second part, although the viewpoint is still Sarah’s, other characters play a full and satisfying part and it becomes a rounded novel.

For me, the intelligent working through of personal abandonment by Sarah, the brilliant holding of tension as the mystery unravels and the fact that she, the protagonist, brings out her own strong conclusion are the strengths of this narrative. For fear of spoiling the end, I am not about to disclose more of the storyline – but it is a compelling and satisfying first novel.