Published by Short Books 14 March 2013

176pp, hardback, £12.99

Reviewed by Paul Sidey

This is a short memoir published by Short Books. When the author was only four years old, his father abandoned him and his family for another woman. Christiansen never saw him again.

Christiansen’s grandfather was editor of Beaverbrook’s Express, his father editor of the Daily Mail, a mistress to whom he was devoted. Rupert, named after the eponymous bear of the famous Express cartoon series of the fifties, is the opera critic of the Telegraph. Words are in his blood. He writes observantly, succinctly and with great compassion about his mother.

There was also a cache of letters for the author to work through, but, as a detective story, I Know You Are Going To Be Happy hardly comes up with anything revelatory. As an exercise in exorcism, perhaps the investigation into the past has been a help for Christiansen in coming to terms with himself. But compared, say, with Jeanette Winterson’s memoir about her stepmother, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? even his title does not issue the same kind of challenge.

Where Winterson’s account of a surreal, cruel childhood has both a visceral intensity and a marvellous, life-enhancing humour, Christiansen’s Pett’s Wood upbringing, however sad, cannot compete. He is a good, experienced writer, but it is a mystery why he felt the need to put this autobiographical fragment on record.

Candia McWilliam – whose own recent memoir was nakedly confessional about her personal scars – is quoted on the back panel of Christiansen’s book, commenting admiringly of his ability to evoke ‘the history of consciousness and its conscience, both richly aware and unfashionably, grandly fierce’. I guess I must have missed something.

The publisher’s blurb also suggests that I Know You Are Going To Be Happy ‘chronicles with novelistic power a generation for whom the experience of the Sixties brought emotional chaos as well as liberation’. But I don’t see that readers of Christiansen’s memoir are going to come away with a sense that a period has been recreated with great dramatic intensity, any more than the author achieves in the search for emotional motivation and some kind of closure as regards the father who deserted him.

I believe it takes a strong visceral reaction to devote time otherwise better spent eating, sleeping, and drinking espresso to the formulation of a lengthy – or even brief, nowadays – and articulate response, and I therefore suspect the reviewer is more engaged than he lets on.

This reader envied Rupert Christiansen his title at once. I KNOW YOU’RE GOING TO BE HAPPY is the ultimate punch-line, particularly when the well-wisher prefaces with “You don’t know how sorry I am that I can’t be in at the kill.” Warning to prophets and congratulants: Maybe say, “I hope – I hope you’re going to be happy.” Or “I wish you the best of luck.” And avoid euphemisms containing the word ‘sorry’ and, most of all, just don’t say ‘kill.’ Isaac Newton refrained from unreservedly confirming ‘the time of the end’ so as not to fall prey to the folly of false doomsayers. Perhaps this is more a tale for unrealistic optimists, which is just as well. They deserve to be rewarded for reading, and Christiansen movingly rewards.

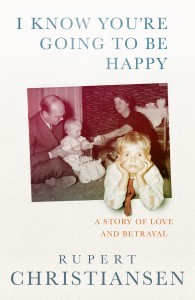

Behind the smiles among the mug shots in family albums, behind the eyes, what is more heart-rending than premonition is absolute innocence. Like six year old Rufus Follet in James Agee’s A Death in the Family, Christiansen is the artist painstakingly putting the pieces back together in order to recreate the day his world was smashed; unlike Rufus, Rupert did not have the solace of the tragic victim; he couldn’t hang out on the corner like Rufus and say, if only to find a shape for a new and dread reality by trying it out in words,”Today my Daddy died.” Daddy was alive somewhere. Nobody could say his Maker had taken him. His Mistress had taken him. And it was unmentionable. What notion of love was staged on the day of that family sitting, I find myself wondering. And if the corrosion of hypocrisy has always jammed the workings of our lives, who better than the child as articulate author to testify? And who more articulate than Rupert Christiansen?

If jinxed blessings and doomed marriages are not news, as Christiansen’s delve into the crossed-loves of Greek tragedy confirms – unless you happen to be famous, as the tabloids bank on – maybe hearing from their fodder is. Anna Karenina was not much of a cautionary tale; divorces have been on the rise ever since, and there are reportedly more single-parent families today than ever before. And it is probably true that for every childhood shattered by divorce and abandonment, there is one more shattered by some other calamity, or by the trauma of parents who should separate but don’t.

But imagine Seryozha, the Karenin kid, long grown, finding, among the pruned correspondences of a felled past, a letter, for some reason preserved, promising his parents conjugal bliss. Picture him considering the idyllic family photo framed as if by Ingmar Bergman in deception edged with gilt.

At the very least, Christiansen holds two pieces of crucial evidence that circumscribe his life, that help define it, and that, like him, survived, up to the light.

They were false expectations and inaccurate images, but how do you divine the accuracy of a hope or truth behind a smile? How do you cleave vengeance from justice, indifference from marriage, unfaithfulness from love, victimization from parenting? These are questions worth raising in a lesson for love as much as on hate.

Christiansen riveted me with the elegance of his pain. Dude got style. It is not easy to howl in an understated, almost whimsical voice. It’s above the didactic, the shame, the blame. It is more asking than telling.

The majority of readers on the planet seek, beyond titillation – I speak from a woman’s point of view, admittedly – something that will admit some shaft of light, any shaft of light; something that will, if only in the beauty of its expression – and that’s a loaded “if only” – take a sad song and make it better, for our own sakes and the big if only of our childrens’.

I for one am grateful to the author for these reflections. And I found myself humming – thinking for some reason of torture by immersion in ice – the words a true artist, I would guess, would address to herself or himself, to an audience, and to the critics: For well you know that it’s a fool who plays it cool by making the world a little colder.