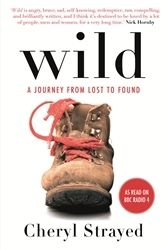

Published by Atlantic Books 15 January 2013

336 pp, paperback, £12.99

Reviewed by Charlotte Moore

At 26, Cheryl Strayed found herself ‘very loose in the world’. She had no contact with her abusive father. Her beloved mother had died, quickly and horribly, from cancer. This catastrophe broke up the family; relations between Cheryl and her sister, brother and step-father, once close, had become distant. Her marriage fell apart under the pressure of her grief. She didn’t finish her degree, but remained burdened with her student debt. Anchorless, she drifted into casual low-paid employment, aimless travel, promiscuity, heroin use.

To survive, Cheryl had to re-invent herself- no, that isn’t her original surname; she chose it herself. She set out to walk the Pacific Crest Trail. The PCT was ‘a world that measured two feet wide and 2,663 miles long’, providing her with a focus combined with a sense of vastness. Overburdened, untrained, alone, she set off from Mojave in Southern California and arrived three months later at the Bridge of the Gods, on the border between Oregon and Washington.

In a sense, not much happened. She saw bears and rattlesnakes; she nearly ran out of water; she met a couple of sinister men, as well as a surprisingly large number of cute ones. She suffered acutely from her outsize backpack and her too-small boots; she’s good at describing the minutiae of physical discomfort. But as tales of human endurance go, Wild is fairly tame. The narrative begins with a heart-stopping moment when one of her boots hurtles irretrievably into the abyss, but we later find out that a new pair of boots awaits her at a settlement a few miles further on.

This isn’t a guidebook, or even a travelogue. Strayed writes competently, but her descriptions of landscape and wildlife are for the most part generic. I finished the book with few clear mental pictures of the journey. Strayed shows little curiosity about the PCT. Most birds are just ‘birds’, trees and flowers are background, animals, even quite mild ones, are to be feared rather than studied. She rarely asks how a lake or a mountain or a settlement got its name; there is almost no sense of history, either local or national. It’s not that she’s unappreciative; she’s moved by spectacular sunsets and pure blue lakes. But her power of making such things come alive for the reader is limited, partly because she’s never objective.

‘I thought about the fox. I wondered if he’d returned to the fallen tree and wondered about me.’ ‘I saw that I was surrounded by hundreds of azaleas in a dozen shades of pink and pale orange… They seemed to be a gift to me.’ ‘The sun stared ruthlessly down on me, not caring one iota whether I lived or died.’ What Strayed really knows about, what she really wants to write about, is herself.

I’m not being as critical as I sound. As the account of an emotional journey, Wild succeeds magnificently. Far more interesting to me than her hiking narrative were the flashback scenes dealing with her childhood and the loss of her mother. The episode where she and her brother decide to kill their mother’s old horse, for instance, is harrowing. So is the moment when she swallows her mother’s charred bones. Strayed writes without inhibition. Her needs are intense, and intensely conveyed, whether they be for love, heroin, money, sex, sticking plasters, or Snapple lemonade. She is endearingly candid, her self-preoccupation redeemed by a generous spirit and a sense of humour. I’m glad that her PCT odyssey brought her the peace of mind she craved, and deserved.