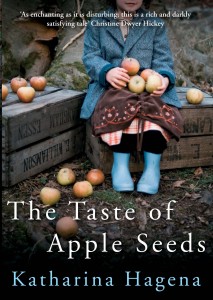

Published by Atlantic Books 1 January 2013

256pp, hardback, £12.99

Reviewed by Elizabeth Hilliard Selka

Anna Deelwater has a particular way of eating her favourite apple, a tart-tasting heirloom variety called Boskoop. She starts at the top, by the stalk, and eats slowly down the fruit, core and all except for the seeds (or ‘pips’ as they are called in British English). These she saves and chews for hours, even though her big sister Berthe warns her they are poisonous. Anna likes them because they taste of marzipan. All this Iris Berger learns from Berthe, her grandmother, because Anna is dead long before Iris is born. She died young, aged only sixteen – of pneumonia, nothing to do with the properties of apple pips.

Iris has come back to the family home because it is now hers, bequeathed to her by Berthe who died recently but had been long gone, her mind lost to dementia. The house is inhabited by memories, Iris’s own and those told her by Berthe long ago, memories of people and events which echo around the place and in Iris’s mind while she reflects on her forebears, her past and her future. The house, its garden and its setting in a German village some time in the later twentieth century (Iris’s grandmother rode in a carriage, and her grandfather was involved in the Second World War) are at the heart of the tale, for Iris and for us. Even the furniture seems significant, and the contents of the wardrobes as Iris extracts long-neglected gowns and wears them around the place and to the shop to buy groceries. She is exploring her past, savouring it, testing it for size and fit, before deciding whether to cast it off or embrace it here in this place.

So, we have Iris, Berthe and her sister Anna. Other figures in Iris’s past are her mother Christa, and Christa’s sisters Inga and Harriet (or ‘Mohani’ as she now prefers) and Harriet’s daughter Rosmarie; also Iris’s late grandfather (Berthe’s husband) Heinrich ‘Hinnerk’ Lunschen, a moody old fellow who at one time was a member of the Nazi party. Then there’s the local schoolteacher, Karsten Lexow, who is now an old man but has a secret to divulge to Iris, and Max Ohmstedt, a young man in love with Iris who also has connections which go back into Iris’s childhood. Frankly, it is helpful to draw yourself a family tree and list of characters as they appear, to prevent becoming confused in this maze of names and relationships. Then you can enjoy this lovely book for its best qualities.

It is relationships, the memory of them as much as the present reality, that preoccupy Iris. She must find her own way through the maze, and it’s not simple, just as it isn’t in real life. There are no big scenes, no tantrums, just a progression of moments, past and present weaving together into the texture of Iris’s life here, now, in this house. The novel has a meandering, ruminative quality which might be frustrating if Iris weren’t so simply likeable, if we didn’t care what becomes of her. She shares with us her dilemmas, her thoughts and perceptions, and for the quiet hours it takes to enjoy the evocative taste of apple seeds, we are hers entirely.

It is heartening that such a subtle, slowburning saga has become a bestseller across Europe since first publication in 2008, and not surprising that it has been made into a film – a German-language production starring Hannah Herzsprung who was in The Reader – so sensual and visual is the novel. How long till Hollywood follows suit?