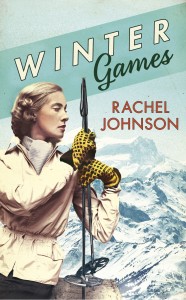

Published by Fig Tree 1 November 2012

Published by Fig Tree 1 November 2012

336pp, hardback, £14.99

Reviewed by Zoë Fairbairns

‘No daughter of mine will go to Oxford as a commoner,’ proclaims a 1930s father of teenage girls in Rachel Johnson’s novel Winter Games. Whether your response is ‘quite right too’ or ‘what’s a commoner?’ [1] will depend on your background and values, but for him the solution is simple: dispatch his daughter Daphne to a finishing school in Bavaria.

Here she can not only brush up her German in preparation for her scholarship exam, but also participate in the efforts of some British toffs to prevent war by making friends with the Nazi establishment, and encouraging their debby daughters to act as unofficial ambassadors for the régime: ‘We played our part,’ one of them recalls later. ‘The regime was thrilled to have us. We came home full of the joys of spring, chattering about full employment, maternity clinics and fast new roads.’

Daphne herself, when not visiting the Winter Olympics or joining the Bund Deutscher Mädchen – the ‘girlie version of the Hitler Youth’ – worries about the disappearance of a Jewish classmate. Daphne undergoes something called Formation of Character in Mind and Communal Life – this includes learning to ski, running barefoot in the snow in the early morning with hot baked potatoes clutched in her hands to keep her fingers from freezing, and being impregnated by a Nazi intruder who enters her room and her body while she sleeps.

Decades later, in the present day, another young woman is setting off from the UK to Germany: she’s Daphne’s granddaughter Francie, a journalist who, bored with her husband Gus who is kind and loving, has fallen for her boss Nathan, who isn’t. Nathan has a nice cock, apparently, and the power to sack Francie from her staff job, which he does, offering her instead a freelance assignment to research the tourist industry in Bavaria. Francie notes ‘sites of special historical interest to Third Reich anoraks, such as Hitler’s chalet and…Göring’s summer residence’, but is under strict instructions from Nathan to avoid having ‘some horrific mash-up of the Final Solution and hot-stone massage in the same piece.’ Francie also embarks on a personal quest to find out what exactly happened to her beloved grandmother during her German sojourn in the 1930s.

Rachel Johnson’s novel is energetically written – sometimes too energetically, as the dizzying flashbacks, flash-forwards and switches of point of view make it difficult at times for the reader to know where s/he is, and who is thinking what. When Francie is described as ‘pretty, quite tall but nicely rounded, straight nose, mouth that reminded men over a certain age of Carly Simon’, you wonder whose impression that is and how they know so much about what ‘men over a certain age’ think. When Hitler is described, at the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics, as ‘a slight, feverish-looking man who looked as if he should be in a mental asylum’, it’s not clear whether this is an editorial comment, or whether it is the view of Daphne who, just as quickly, is moved and impressed by the Führer: ‘Even Daphne felt her eyelids pricking with emotion.’ ‘The winter games of February 1936,’ we are told, ‘could already be counted a triumph.’ Counted by whom? There’s too much editorializing from an unidentified narrator who is sometimes a know-all and sometimes a tantalizing keeper of secrets. The book is grimmer, more telling, more haunting, more ironic and more fun when events are seen solely through the eyes of either Daphne or Francie.

Distasteful comparisons are drawn between the lives of rich young women in the years leading up to World War Two, and the supposed dullness and ease of the present day: ‘It was all so…tumultuous, compared to now,’ Francie reflects on her grandmother’s youth. ‘Daphne’s children and grandchildren lived through plodding peace-time. The high points of history had been the fall of the Berlin wall, Thatcher resigning, the death of Diana and 9/11, events Francie and Gus had mainly watched from the comfort of their Roche Bobois sofa, glugging Pinot Grigio.’ Is that supposed to be a bad thing? Wasn’t that part of the reason why so many of Daphne’s generation sacrificed so much in World War Two – so that at least some of their descendants could enjoy ‘plodding peacetime’? Despite some lively presentation of fascinating historical material, Winter Games is an uncomfortable read, partly because it is so disorganized and partly because it lacks a moral centre, a coherent point of view on its own troubling material.

[1] I googled it so you won’t have to: apparently a commoner is any undergraduate member of the university who has not obtained a college scholarship or exhibition. An exhibition is… oh, look it up yourself.