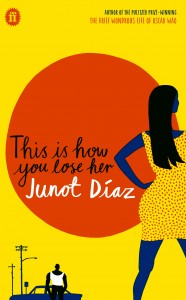

Published by Faber and Faber 6 September 2012

Published by Faber and Faber 6 September 2012

224 pp, paperback, 12.99

Reviewed by Catherine Jones

Love in all its forms gets the once-over in this collection of New Jersey Dominican voices, linked by Yunior, the lesson-learning character at its heart, who is destined to have the ‘footprint of fresh disaster’ on his soul. The precarious wit of the love-struck, the inevitable mourning of the sexual chancer, the bitter lack of expectation of the mistress – all are laid bare with details that hide a story in each small shell of a sentence.

Dominican-American Diaz, who won the Pulitzer in 2008 for his novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, has said he enjoys telling ‘stories with a central absence’ and favours the form of a linked story collection, remarking, ‘I guess I’m just hopelessly fascinated by the realities that you can assemble out of connected fragments.’

To begin, in ‘The Sun, the Moon, the Stars’, Yunior marks losing an early, important relationship with the effortless humour of a young man still dull about love, describing his girlfriend’s discovery of his affair thus: ‘She threw Cassandra’s letter at me – it missed and landed under a Volvo – and then she sat down on the curb and started hyperventilating.’

A sense of menacing disappointment travels with the couple on a make-or-break holiday to Santo Domenico; on the one hand she is too sensitive – ‘takes to hurt the way water takes to paper’ – but she has also been dressing better and going out, after discovering the games he was playing. ‘Making me aware of my precarious position in her life,’ is how Yunior sees it.

Each sentence ripples with throwaway brilliance – ‘a flapjack of makeup’ on the faces of fellow passengers on their faces. The street where he was born ‘hasn’t decided if it wants to be a slum or not’. Their resort has courtesy golf carts, ‘beaches the way the rest of the Island has got problems’, and everywhere a wealthy European with a young ‘dark-assed Domenican girl’ on his arm. Remarks Yunior, ‘You can tell by their inability to communicate that these two didn’t meet back in their Left bank days.’

In ‘Nilda’, a 14-year-old recalls a raft of his brother’s girlfriends – ‘I don’t remember her name, but I do remember how her perm shone in the glow of our night-light’ – in a piece that resonates with the fleeting possibilities of adolescence, how fresh they seem until you look back. In ‘Alma’, the cheater’s moment of discovery is described with the mournful wit of a man accepting the inevitable – ‘your heart plunges through you like a fat bandit through a hangman’s trap’.

The heads and tails of love are here: men being caught – as inferior morally or intellectually; the strength of lust against the weakness of the head; women being strong and quiet and bitter, with the ‘scared, hunted look of the unlucky’ or with ‘a mouth like unswept glass – when you least expect it she cuts you.’

There are days ‘the colour of pigeons’, there are realizations too – ‘This is what I know: people’s hopes go on forever’. Running through is the sense of dread of the trapped, in or out of a relationship, and how close in meaning are the words loss and love. ‘You don’t want to let go, but don’t want to be hurt, either. It’s not a great place to be but what can I tell you?’

In ’Invierno’, Yunior – with a brother who wants to be buried in his car with his TV and boxing gloves – relates his childhood with a mother keen her two sons learn English. ‘She saw our young minds as bright, spiky sunflowers in need of light, and arranged us as close to the TV as possible to maximize our exposure.’ In their new home – away from Santo Domenico – the brothers ‘squirted acid at each other with eyes, like reptiles’ as their mother – ‘with a tight, guarded smile that seemed to drift across the room the way a shadow drifts slowly across a wall’ – dances attendance on her husband and his infrequent dinner guests .

All love’s voices are here – the pitiful, crestfallen, the older mistress, Miss Lora – ‘the black waves of her hair flowing behind her like a school of eel’ in the swimming pool – tapping an upbeat rhythm to determinedly cheerful hopelessness, and the man at the heart of it keeping an attitude going because what else do you do?

Over the last 16 years, Yunior has been an integral character for Diaz, and the author describes This is How You Lose Her as ‘one cheater’s tortured journey through to real heartbreak, a crisis from which he emerges, if not necessarily cured, at least closer to possessing something we could call an authentic human self’.

I raced through these stories, longing to start back all over again, not wanting the relationship to end. This is, no doubt about it, how it should be done.