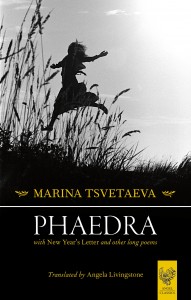

Translated by Angela Livingstone

Translated by Angela Livingstone

Published by Angel Classics 27 September 2012

160pp, paperback, £11.95

Reviewed by Charlotte Moore

Marina Tsvetaeva is one of the greatest Russian poets of the twentieth century. It comes as a surprise, therefore, that her 1927 verse drama Phaedra and ‘New Year’s Letter’, ‘Poem Of The Air’ and ‘Attempt At A Room’, three long poems thematically and stylistically linked to it, appear for the first time in English in this volume.

Tsvetaeva’s life was full of horror and sorrow. One daughter died of starvation during the Civil War; the other was later sent to a prison camp. Her husband, who had fought against the Bolsheviks, became a Soviet informer behind her back, and was eventually executed. Her love affairs with Rainer Maria Rilke and Boris Pasternak were unrequited or unsatisfactory. In 1941, Tsvetaeva hanged herself. In so doing, she was at least spared the pain of her 19-year-old son Georgy’s death, killed in action with the Soviet Army.

No wonder she was drawn to the legend of the doomed Phaedra, consumed by a fatal love for her chaste stepson Hippolytus. Every line of verse burns with passion. Hippolytus’s adoration of his dead mother Antiope; Phaedra’s former wetnurse’s elemental obsession with her ‘nursling’; the savage rage of Theseus, Phaedra’s husband, who blames his son Hippolytus for her death – it’s all related at fever pitch. Phaedra herself is driven to the edge of sanity by a force she cannot control. The nurse calls it a ‘battle of blood and reason,/ one half fights the other half,/bole at war with ailing heartwood/Ancient song, an ancient story.’

The nurse is given the most original treatment of the four main characters. She is a figure from Russian folklore, at times witch-like, her speech like an incantation. All her emotional life is channelled into Phaedra, whom she urges towards Hippolytus – and therefore towards death -as if seeking her own erotic fulfillment through the consummation of her ‘pretty darling’s’ desire; ‘Feed upon my wisdom, just as / once you fed (so sweet those hours!)/ upon my milk, and it was whiter/ than goddess-foam.’

It is hard for poetry in translation to avoid sounding muffled, or clunky; the high quality of Angela Livingstone’s work occasionally lapses. But her word choices are careful and intelligent and her introduction is helpful. Overall, she succeeds in conveying the tragic intensity of the original – the intensity which leads to catastrophe but without which there is no knowledge, in Tsvetaeva’s vision.