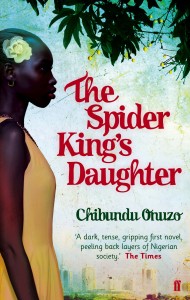

Published by Faber 15 March 2012

Published by Faber 15 March 2012

288pp, paperback, £7.99

Reviewed by Zoe Fairbairns

‘What does one wear if one is going out with a person of lesser social standing?’ wonders 17-year-old Abike Johnson, whose father is a wealthy Nigerian businessman and whose mother is a former film star. Abike is preparing for her first date with a hawker who sells ice cream in the streets of Lagos.

The ice cream doesn’t sound particularly appetising (‘Biting into the plastic, I squeezed the bottom and spurted cold sweet milk on to my tongue’), but Chibundu Onuzo’s debut novel The Spider King’s Daughter is delicious, at least to start with. Abike and her hawker aren’t exactly milady and the raggle-taggle gypsy, Lady Chatterley and her lover, or Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio on board the Titanic, but their story is evocative of these archetypal, socially-mismatched pairings, none of which ran into the technological dilemmas of twenty-first century love across the social divide: ‘I don’t know where going to Yale will leave my hawker and me. A long-distance relationship is impossible with someone who doesn’t have a phone.’

The hawker used to have a phone – and private education, and domestic servants, and nice clothes and use of a car. Abike spots this at once: ‘The label “used to be rich” hangs from everything that concerns him … He spoke pidgin to some of his customers, but the English he used with me was confident and without traces of the grammar you expect from drivers, hawkers etcetera.’ So she’s not venturing too far outside her social comfort zone by associating with him. ‘He wasn’t just a hawker. He was a hawker I was considering adding to my circle of friends.’ Showing off her bit of rough is part of the fun, as is winding up her dad.

This witty, emotionally honest, disconcerting love story is told in the first person – two first persons, with typefaces distinguishing between Abike’s version of events and that of her hawker, who is never named. Their differing versions make for an edgy read, in which the reader is frequently wrong-footed.

Lagos is portrayed as a dangerous place, where ‘the papers are always full of armed robbers who are hawkers in the daytime’, and where beggars seek to improve their prospects by having a limb amputated. A job as a seamstress may be a route into forced prostitution, and even a cosseted rich girl who dares to step outside her father’s chauffeur-driven jeep wearing clothes of her own choosing runs the risk of being mistaken for a piece of meat. As in other parts of the world, sexual harassment by men is blamed on the shortness of women’s skirts.

Most of the story is surprisingly passionless: the pair kiss and hold hands but not much else. Of course there is no law that just because they are teenagers they have to tear each other’s clothes off at every opportunity (perhaps Nigerian teenagers don’t do that), but you’d think they would at least talk about it, or one or other of them would try it on.

The hawker is in thrall to another passion: the passion for revenge. Passing between the different layers of Lagos society, he is able to learn from both. When he finds evidence implicating Abike’s father and the corrupt Johnson Corporation in the death of his own father, as well as the sexual abuse of a friend, he resolves on murder. He obtains a gun without difficulty and brings it to one of Abike’s million-naira parties (‘a million was only four thousand pounds, a handbag’).

The denouement is sad and soaked with blood: the blood of the dead body in the swimming pool, and the Johnson blood which flows in Abike’s veins. Bereft of her hawker, she embraces another future: ‘I am an 18-year-old woman who has chosen to run Johnson Corporation instead of going to university … Send in the Minister.’