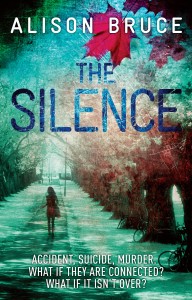

Published by Constable 19 July 2012

Published by Constable 19 July 2012

320 pp, hardback, £18.99

Reviewed by Debbie Taylor

Hoping to do for Cambridge what Colin Dexter did for Oxford with his Morse series is crime novelist Alison Bruce – but her maverick D.C. Gary Goodhew is no Endeavour Morse. In fact the one real flaw in this otherwise engrossing and well-plotted novel is the oddly flat characterization of her main protagonist. So although we first encounter Goodhew doggedly disobeying orders, as per, and nabbing a ne’er-do-well in a dark alley while the rest of the force is impotently occupied elsewhere, there’s little in Bruce’s depiction of our hero to set him apart from the Kincaids and Markses of the team.

The story proper opens with a stabbing – in the jugular, with a flat-head screwdriver, in the car park of the Carlton Arms – of local high-school alumnus-turned-computer-whiz Joey McCarthy by a shadowy assailant who darkly declares, ‘I know everything.’

Jump-cut to A-level student Libby Brett sending confessional Facebook messages to a curiously laconic school friend of her older sister Rosie. It emerges that sister Rosie nipped out to the cinema one evening three years back and ended up tumbling from a motorway bridge on the A14 and splatting onto and under various speeding vehicles on the road below. Libby’s never accepted the verdict of suicide, either for Rosie or for brother Nathan, who snuffed it shortly afterwards, and she’s using this faceless Facebook correspondence as a way of mulling over their deaths.

As a flashback device this just about works and gives us an engaging first person narrator to care about and (later) fear for – which is perhaps why Goodhew and associated police procedural shenanigans seem somewhat uninvolving by comparison.

Young Libby lives chastely with Matt (who is dead brother Nathan’s erstwhile best friend) in a big shared house with a motley collection of musical-bed-playing students, including earnest American misfit Shanie, who is teased by the others and goes missing. The house is jointly rented, in absentia, by Libby’s and Matt’s respective fathers, who presumably have keys to all the rooms. Alone in the house one day, Libby overhears someone sneaking up and down the stairs, unlocking everyone’s doors. Later a faint smell of rotting meat starts to permeate the corridor outside Shanie’s room…

But I’m getting ahead of myself, because this book is all about backstory, and how past events have brought all these characters together in the present. Matt’s mother died recently of cancer, brought on, Matt believes, by the stress of marriage to his alcoholic father – to whom he’s therefore not speaking. Libby’s parents are both alive, but similarly estranged. Who is this mysterious school friend Libby is writing to? Why was expat Shanie living in the shared house in the first place? And how is middle-aged Joey McCarthy’s screwdriver stabbing related to all these teenage deaths?

Meanwhile, back at police headquarters, P.C. Gully has the hots for D.C. Goodhew, D.C. Goodhew continues to disobey orders, and D.C. Kincaid is behaving in an oddly distracted manner – possibly due to the presence of Matt’s older sister Charlotte, a testosterone magnet of such inexplicable strength for various members of the police force, and so tangential to the main plot, that I can only assume she has appeared in a previous novel in the series.

Those who know and love Cambridge will revel in the local detail in this book, with individual streets, cafes and eateries all described with affectionate familiarity. But it’s the fate any crime novelist who lights on a winning rubric – Cambridge plus Goodhew in this case – that they are forced to engineer any future story so that it will fit into the same rubric. Some, like Karin Slaughter, accomplish this feat relatively seamlessly. Others – notably Tess Gerritsen in her recent The Bone Garden – crudely top and tail what should by rights be a stand-alone novel with a few derisory scenes with trademark long-term characters. With The Silence, Alison Bruce has constructed an ingenious novel that just about holds its two main elements together and leaves the new reader curious to discover more about Goodhew, Gully et al.