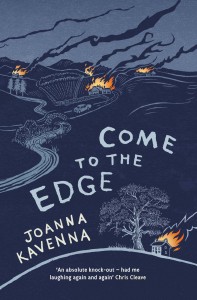

Published by Quercus 12 July 2012

Published by Quercus 12 July 2012

296pp, hardback, £12.99

Reviewed by Sara Maitland

I have heard so much about Joanna Kavenna and what a deft, funny writer she is and her new novel promised a ‘dark satire’ about contemporary rural life; I was really looking forward to this – it should have been more or less made to measure.

But, alas, Come to the Edge did not work for me. Perhaps I am the wrong reader, though I suspect that any rural reader would be the ‘wrong’ one. Perhaps rural life is so different on the north side of the Solway Firth (where I live) from the south side – in Scotland rather than England – that the situation made no sense to me. However no reality in existence includes the making of jam during winter months out of unspecified fruit that no one has picked; and a satire not based within a recognizable reality is inevitably neither funny nor deft.

The idea is that a suburban professional woman flees infertility and her marriage break-up and seeks rural refuge by answering an eccentric advertisement for a sort of unpaid companion/fellow worker on a small-holding in somewhere very like Cumbria (it is Cumbria geographically; it just is not a recognizable Cumbria). The small-holding owner, a red-headed survivalist called Cassandra White, is completely batty; some of the battiness is very funny, but more of it is not. Cassandra decides, for undisclosed reasons, to launch an attack on second-homers by resettling their fancy houses with homeless or semi-homeless locals (of whom there seem to be a remarkable number). Things escalate, partly because our heroine (and narrator) is so enthusiastic about having sex with one of the re-settlers that she forgets to deliver a crucial message, which seems beyond belief even in someone as daft as she is – and everything ends in tragedy, with a massive conflagration of all the houses in the valley and a shoot-out with the police, in which Cassandra gets killed and the narrator wounded and subsequently confined to a lunatic asylum.

The plot is both convoluted and flimsy. But the real problem is the vagueness – and inaccuracy – of the rural community itself. The things that are seriously satirize-able in remote rural areas nowadays are conspicuously absent. The oddest absence is about class; there are no farmers manipulating the Subsidies, wheedling the taxes; there are no ‘officials’ harrying the farmers. No one apparently is claiming Single Farm Subsidy; no one is failing to ear-ring their cows or to fill in the passports; apart from Cassandra there are no middle-class characters at all, just honest sons and daughters of toil apparently working for no one. Where are the off-spring of the older generation who in most communities known to me have had to leave home to get work, but turn up for the holidays and harass their parents with nostalgia? Where are the 3,000+ Polish and other Eastern Bloc workers who we know are in the area? Where are the teachers, nurses, council officials and nature conservationists? Where indeed are the in-coming retirees and artists – not second-homers but committed new residents? Where are the complex, hilarious, delicate snobberies of rural communities? They are not in this novel anyway, so the picture is skewed and thin – and ultimately irritating.

There is not much nature either. In the final throes of disaster the narrator has a vision of the lovely moor (oddly enough with trees on it), but in the novel there is so little detail, no seasons, no insects, no weather. Even the gardening is of an unconvincing kind.

Obviously I am defensive here. I think what is going on in the remaining rural fastnesses of the UK is both interesting and complicated and I find I do not enjoy having it presented as a joke, not underpinned by knowledge. I do not think I am particularly romantic about it, but I do think it is more interesting than Come to the Edge makes it. And the gushy, repetitive, purple writing, although perfectly suited to the narrator, was a final insult to this reader.

(And in case anyone should worry, I can find no evidence anywhere that eating Quinoa – an odd choice for Cassandra who deplores all other imported food stuffs – does not drive people mad, despite the novel’s claim.)

What a pity.