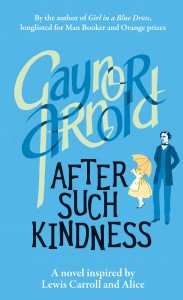

Published by Tindal Street Press 5 July 2012

Published by Tindal Street Press 5 July 2012

386pp, hardback, £12.99

Reviewed by Elsbeth Lindner

Some classics of literature lose lustre as they age – The Return of the Native, anyone? – yet the charms of Alice in Wonderland seem scarcely to have dimmed with the passing years. Tenniel’s illustrations have surely helped, but in essence it’s the Carroll magic that keeps the book alive: the invention; the humour; the sense of a playful, original, Victorian-boundary-busting personality at work. The Dodgson aspect of the book – withdrawn academic/clergyman with a dubious penchant for photographing nymphets – has inevitably dimmed some of the brightness, but the enduring magic, not just of Alice, but The Hunting of the Snark, Jabberwocky, etc, has tended to overshadow the less reputable aspects.

Gaynor Arnold’s new novel – founded in the Carroll/Dodgson facts in a similar manner to the way in which her much-garlanded debut Girl in a Blue Dress drew on Charles Dickens to create a writer named Alfred Gibson – focuses much more on the Dodgson dimension than the Carroll. In other words this is a book less about literary creativity, more interested in Victorian sexuality, patriarchy and the confused and dangerous vision of the child/woman.

Arnold’s Oxford don/mathematician/cleric is John Jameson, a character not only less plausibly inventive than Dodgson but one whose calculated interaction with Daisy Baxter (modeled on Alice Liddell) generates a repugnance that easily overshadows the value of a children’s story book.

Narrated multiply by Jameson; Daisy (both via her childhood diary and in an adult persona, now named Margaret Constantine); Daisy’s father, vicar Daniel Baxter; and others, the novel pieces together Daisy’s interactions with Jameson and her father between ages 10 and 15, a period that the older Margaret seems largely to have mentally obliterated. ‘Awakening’ as an adult, a bit like Alice after falling down the rabbit hole, she finds herself married to yet another clergyman, Robert Constantine, and afflicted with a sexual froideur that has left their marriage unconsummated. To the reader, however, Daisy/Margaret’s experience is a sequence of male appropriations of her freedom, innocence and identity that shows no prospect of concluding as the book draws to a close.

The Baxter vicarage is a predictable microcosm of Victorian social mores, with its upstairs/downstairs divisions, family expectations and elaborate if ineffective parenting. Jameson ingratiates himself into it via a mixture of luck – saving youngest son Benjy from drowning – and intellectual peer pressure. Mr Baxter enjoys Jameson’s friendship and can see no impropriety in the celibate don’s predilection for spending time with pre-pubescent girl children or even photographing them. Daisy is decreasingly chaperoned in Jameson’s presence as he takes her to the theatre in London, to tea in his college rooms and later encourages her to strip for the camera, firstly removing her drawers, later moving to full nudity.

This ‘grooming’ as Arnold refers to it, in an afterword that refers to her own links to Child Protection, is unpleasant enough but is followed by far greater transgressions visited on the child not by Jameson but another. So she becomes the victim of her era, her gender and of the contorted and hypocritical attentions of her supposed guardians.

Sadly very little of this material strikes the reader as especially revelatory, indeed it has been the meat of many previous books, both fiction and non-fiction. (The ghost of Lolita sometimes seems to haunt the pages.) What Arnold brings to the conversation is a closer consideration of this particular literary history and context, and while stating that her novel is ‘not just the Alice Liddell and Charles Dodgson tale in disguise; it is an exploration of a number of themes that interest me; and my made-up story of Daisy Baxter has ramification that never, as far as I know, affected either the real-life Alice or those around her’, an element of infection tends to creep outwards towards Carroll.

Also, after the brio of Girl in a Blue Dress, which told a sad woman’s story too, but still gave full heft to Gibson/Dickens’s literary genius, there’s something not only darker but heavier about the new book. Understandably, perhaps, there’s a lack of enthusiasm for Jameson, but no other character emerges with much warmth attached, not even poor Daisy. Innumerable references to Alice minutiae – lobsters, flamingoes, lakes of tears – only serve to intensify a mood of sadness.

In After Such Kindness, the harm done far outweighs the value of the book that is Jameson’s legacy, Daisy’s Dayream. What of readers of Alice? After Arnold, will they find its charm quite as carefree? It’s a measure, perhaps, of this novel’s quiet insistence that the question remains hanging in the air, rather like the fading smile on the face of a Cheshire cat.