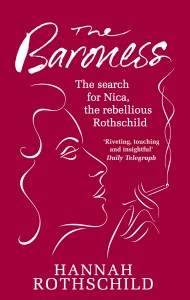

The search for Nica, the rebellious Rothschild

The search for Nica, the rebellious Rothschild

Published by Virago 7 March 2013

320pp, paperback, £8.99

Reviewed by Charlotte Moore

Pannonica (Nica) Rothschild was born, in 1913, into the richest and most secretive of families, then at the height of its power. ‘I was moved from one great country house to another in the germless community of reserved Pullman coaches while being guarded night and day by a regiment of nurses, governesses, tutors, footmen, valets, chauffeurs and grooms,’ she recalled. 74 years later she died in her shabby New York home, surrounded by hundreds of cats, all but written out of Rothschild family history.

The great houses of Nica’s childhood were crammed with priceless works of art. Inside, the children played amongst racks holding thousands of stuffed animals; outside, giant tortoises, kangaroos and emus roamed the grounds. Nica met no children apart from siblings and cousins. Her father Charles – depressive, eventually suicidal – had met her mother while hunting for rare fleas in the Carpathians; the couple named Pannonica, their third, not much wanted daughter, after a moth.

The founding father of the dynasty had decreed that Rothschild women could take no part in running the bank. Nica was denied a proper education or a real career – small wonder that as a beautiful, under-stimulated debutante she should fall into marriage with Baron Jules de Koenigswarter, a glamorous widower who whisked her away in his Leopard Moth on their first date. Nica called him ‘the commander-in-chief’.

Five children and an adventurous war later, Nica, sick of being commanded, began her startling new life in the New York jazz world. She would leave her pale blue Bentley parked outside the basement clubs in which, as a white woman, she was usually in a minority of one.

Nica exchanged white for black, day for night, luxury for squalor. She lost a good deal – her looks, her social circle, the custody of her children. Certainly, her ‘vulgar’ behaviour lost her the approval of her family, though some contact continued. But she found a millieu in which, at last, she felt at home. Above all, she found the love of her life, the jazz genius Thelonius Monk. Accepted by Monk’s long-suffering wife, Nica supported Monk financially, emotionally and – as his health deteriorated – physically. She even went to court in his place, telling the police that his drugs were hers. Her generosity extended to many; Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker, the distinguished saxophonist in thrall to heroin, died in her hotel suite because no one else would take him in.

Hannah Rothschild is Nica’s great-niece. Like Nica, she knew the pressure of ‘failing to live up to the expectations … of my distinguished family. Rothschild opinion is a force to be reckoned with – it took Hannah years to negotiate family opposition and write the story of Nica the black sheep. She vividly contrasts the ‘jewel-encrusted cage’ of Nica’s early life with the bare light bulb and empty fridge of the New York years. Thelonius Monk seems a pitiable monster of cruelty and selfishness, and Hannah Rothschild is unable to convey any sense of his attractiveness, but her passionate attachment to Nica, or to the idea of Nica, results in a rich and engaging narrative of an extraordinary life.

Why was Nica so powerfully drawn to Monk and his world? Partly, her great- niece suggests, because she knew racial intolerance first-hand. The Rothschild millions were only a flimsy defence against the anti-Semitism that was rife throughout Europe during the first half of the century. Nica’s father, while at Harrow, was ‘regularly released like a fox and told to run for his life while his fellow students, baying like hounds, tried to catch him.’ To Nica’s credit, her experience of intolerance led not to bitterness but to an enlargement of sympathy. As for the unresponsive Monk himself, whose ‘first language was silence’, Nica tried to recreate and improve upon her relationship with her (possibly) schizophrenic father which had been cut short by his suicide.In Monk she found a parallel; a man of great talent unable to get through life without tireless and uncritical support. And Monk did, at least, reward her with the many songs he wrote in her honour.

Hannah Rothschild can’t quite decide whether she wants to tell the story like a novelist or like a historian. The result is somewhat jumpy and at times gushing, but never less than heartfelt.