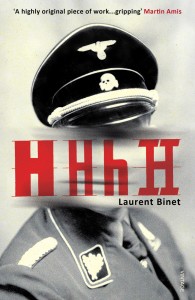

Translated by Sam Taylor

Published by Vintage 3 January 2013

Published by Vintage 3 January 2013

336pp, paperback, £8.99

Reviewed by Elsbeth Lindner

Infranovel? Meta-fiction? Mash-up? Laurent Binet’s book, which won the Prix Goncourt du premier roman and the Prix des Lectuers du Livre de Poche, has an originality that defies simple classification. It’s called a novel by its publishers and a ‘personal’ story by its author. But the narrative happily acknowledges, indeed constantly considers its own invention while simultaneously offering a memorable slice of minutely-researched history, an amiable conversation about writing, and an analysis of how the past can be remembered and recorded. Binet, on You Tube

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9VPxu92-hEo

describes the overall effect as ‘the movie and the making of together’.

HHhH is the acronym of Himmler’s Hirn heisst Heydrich (German for Himmler’s brain is called Heydrich). Rheinhard Heydrich, aka The Hangman, The Butcher, The Blond Beast, The Man with the Iron Heart (this was Hitler’s nickname for him) was the principal architect of the Final Solution and chief of the Nazi secret services. ‘Almost anywhere you look in the politics of the Third Reich, and particularly any of its most terrifying aspects, Heydrich is there – at the centre of everything.’

HHhH is the acronym of Himmler’s Hirn heisst Heydrich (German for Himmler’s brain is called Heydrich). Rheinhard Heydrich, aka The Hangman, The Butcher, The Blond Beast, The Man with the Iron Heart (this was Hitler’s nickname for him) was the principal architect of the Final Solution and chief of the Nazi secret services. ‘Almost anywhere you look in the politics of the Third Reich, and particularly any of its most terrifying aspects, Heydrich is there – at the centre of everything.’

Promoted to Protector of Bohemia and Moravia in 1941, Heydrich moved to Prague where his brutality in suppressing the Czechs became legendary. The focus of Binet’s book is the set-up, execution and horrific aftermath of Operation Anthropoid in May 1942, arranged by the British with the aim of assassinating Heydrich.

While passionate in his hatred of Heydrich and Nazism (Binet the author is, as he reminds us, the son of a Jewish mother and a Communist father) and fascinated by his material, the author is perpetually mindful of the oddity of historical reconstruction. He refers to hypotyposis ‘which means making a scene so lifelike that it gives the reader the impression he can see it with his own eyes.’ He offers vignettes with dialogue, then negates them, rewrites them, considers why he wrote them as he did, refers to other cultural influences – films like Patton, The Pianist and Chaplin’s Great Dictator, books like Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones – which bleed into his imagination and shape his thoughts.

Irritating though this could easily be, Binet’s narrative skill, affability and the powerful nature of the story he does deliver, plus the fascination of his parallel preoccupation, combine to create a text simultaneously compelling, provocative and persuasive.

Is it based on truth? (The research referred to would suggest yes.) Is the narrator reliable? Should the reader mind (or believe), for example, that Binet chose not to buy a book written by Heydrich’s wife because it was too expensive, or just enjoy the joke? (He later reveals he bought it anyway.)

The entire package is hard to resist. There’s authority here, passion, wit, intimacy and true tension when the assassination plot reaches its peak. There’s profound sorrow too, at the vast, often arbitrary cruelty of the war in general and the Czechoslovakian events in particular, alongside sincere acknowledgement of the many instances of heroism, even the undocumented ones.

Easily classifiable or not, this book, as it chips away at the calcifying effect of cliché and stereotype, joins the ranks of significant, original literary responses to a period in history which continues to defy belief and challenge the power of words to express. Binet, born in 1972, belongs to a new generation approaching the horrors of the past with modernity and freedom as well as sincere, abiding respect.