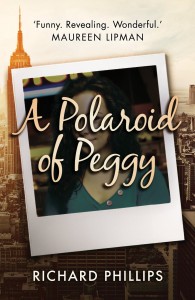

Published by S&G, £7.99, available on Amazon

Imagine a story of lost love and lost bearings, Bonfire of the Vanities meets Love Story with a dash of Mad Men thrown in, if you will. That’s the premise of the new novel from Richard Phillips, a writer and radio broadcaster who once lived in adland. In A Polaroid of Peggy, Andrew Williams has a booming business, a lovely wife, beautiful kids and a wonderful home. All’s looking pretty great, until an old photo turns up, tipping Andrew’s world upside down.

To sample an extract from this comic, poignant work of fiction, read on.

*

London 1999

I was sufficiently long in the tooth to know that when you are accused of something, or asked a question which might lead you to being accused of something, truth should always be your first line of defence. Not only is the weaving of tangled webs neatly avoided, but I have always found that it is far easier to face someone down when you use the truth to do so, even if, as in this case, you are using it to conceal a greater truth that lies behind. So when Alison demanded to know who the girl in the Polaroid was, and after I had got over the shock of seeing the face of someone whom I had once worshipped, suddenly snatched out of the past and dumped into a very, very different present, I answered with what I hoped was an air of total unconcern: ‘That’s Peggy. I knew her in New York about a hundred years ago. Where did you find that?’

So: About this air of total unconcern I was trying for. Did I pull it off? How could I? If you were one of those Indian holy men who’s given away all his worldly goods and wears nothing but a loin cloth, I’ll bet you’d still have ‘guilty as hell’ written all over your face every time you walked through customs. It’s human nature. And if a customs officer or one of those community support chaps who’s not even a proper policeman can make an innocent man feel like that, it’s as nothing compared to what a wife can do.

So Alison carefully weighed my answer and then gave me one of those looks that only a wife can give. She did nothing but raise her eyebrows a half smidgeon but the message was clear. Peggy might have been someone I’d known a hundred years before in New York but there had to be more to it than that. I fought back by making an assault on the moral high ground; what the hell did she think she was doing going through my things – never mind throwing them out – without asking me first? Schoolboy error; in complaining – or pretending to complain – about her going through my things, I was implying that there might be something in there I didn’t want her to see. And she’d just found out what, hadn’t she?

Peggy indeed! The fact that I hadn’t seen her for the last twenty years, and hadn’t even met Alison until half a dozen after that, made me just as guilty as if I’d been caught red handed in a three-way with the South African nanny and Spot.

New York 1979

Peggy and I wandered back down Fifth Avenue with the rest of the crowd dribbling out of the Robert Palmer concert that had just reached its exhausted finale in Central Park. It was part of the annual Dr Pepper Central Park Music Festival and whatever Robert Palmer may have thought, I, for one, was extremely grateful for their sponsorship, because it was one of those unbearable summer nights in Manhattan – very late summer, it was already September – when the humidity is a thousand per cent and even the most refined of ladies glistens buckets. We grabbed the ice-cold cans that were being handed out as we left the arena and not just because they were free. On a night like that, an ice-cold anything is a lifeline. With my de rigueur denim jacket slung over my shoulder – don’t know why I’d bought it, far too hot to wear, but once a fashionista always a fashionista, I suppose – I tossed back my head and drained the lot.

‘You like this stuff?’ asked Peggy. ’Actually, I’ve never had it before. We don’t get it in England.’ ‘We don’t get it here either,’ said Peggy. ‘I mean, we do, but I don’t know anyone who ever, like, gets it.’ ‘Somebody must,’ I said. ’Yup. Somebody must. I guess somebody must.’

Yes, you’re right. An utterly unremarkable, nothingy, so-what exchange and yet, for me, intoxicating. It was the rhythm of Peggy’s voice that I swooned over. The little staccato bursts, the subtlest of inflections, the bone dry delivery. It was pure essence of New York. Not the On the Waterfront, Hell’s Kitchen, Hey-Youse-Gimme-A-Cawfee Noo Yawk. But something else; sharp, smart, sassy, seductive. Yes, all those clichés that, when put together, beget another whole alliterating string of them: Manhattan, Martinis, Madison Avenue. It was all there in Peggy’s voice, every time she spoke.

So maybe you’re thinking it was the idea of Peggy that I was so infatuated with. That any pretty uptown girl might have done just as well. It’s a legitimate debating point, and I will admit that maybe there’s the tiniest scintilla of truth that I was, indeed, in love with the idea of a girl like Peggy. After all, I was, with one or two minor caveats, in love with everything ‘New York’. But inside Peggy’s New York wrapper was someone who rang so many bells for me, I would have become every bit as besotted with her if she’d come from Nanking or Narnia.

I had the not very original idea – still do – that love is a wavelength thing. It’s just a question of finding someone who is on the same one as you. Nobody that I have ever met – not before nor since – received my signal and sent back hers so clearly, with so little interference, as Peggy. No moody dropout. No emotional static. It was, for those few short months, such an unburdening relief to find someone to whom I could get through and who came through to me. As I had had so little real hope of finding someone like that – never got remotely close to it before so why should I ever? – I was simply amazed. And even more amazing was Peggy’s often given and never solicited – well, only very rarely solicited – assurance that the feeling was entirely mutual. There was Peggy in this relationship, there was me, and for the first, and perhaps only, time in my life, there was a real, almost tangible ‘us’, the sum that was greater than the parts.

So, given all this, how on earth had we managed to get ourselves into a situation where tonight would be our last?

London 1999

It should have been an all-hands-to-the-ground, hit-the-pump-running kind of a day. Or something like that. I was very confused that morning.

Usually, the adrenalin rush of being flat out gets my thinking Sabatier-sharp and already the new client had been on the phone to Vince telling him that he wanted a dozen things done. A dozen things done in addition to the hundred and one things we were already doing for our old clients. But I was never daunted by pressure – just bring it on! As a rule I’d be fizzing with ideas, firing out instructions to all and sundry, whipping everyone up into a lather of enthusiasm.

But not that day. That day was different. I was subdued, I was distracted, and, frankly, all over the place.

‘Are you feeling okay?’ asked Vince, not very solicitously, as he barged into my office.

‘Ever heard of knocking,’ I said, not even bothering to swivel back to face him. I was in my state of the art, ergonomically efficient, king-of-the-world office chair looking through the rain-spattered window at the Fitzrovia street scene half a dozen floors below. For some reason, I remember – I mean I don’t remember the reason, I just remember doing it – I was fixating on a bloke trying to get a floor lamp through the back of his hatchback. However many times he tried, and at whichever angle he tried to fit it in, he couldn’t get the door to close. Perhaps I felt there must be some kind of symbolism in this, but I have no idea what I thought it might have been.

‘I have heard of knocking, yes,’ said Vince, ‘and for what it’s worth Julia threw herself bodily in front of me to stop me disturbing you, but we were supposed to be having a meeting in Delibes twenty minutes ago, and everyone was there but you. Thought I’d enquire why.’

(FYI: Julia was my uber-loyal, faux-posh PA and she’d thrown herself bodily in front of a lot of people but not usually to stop them from entering. Quite the reverse, boom, boom.)

New York 1979

It doesn’t matter whether you’re sixteen or sixty-four – as I now know from too much personal experience – after the euphoria of that rare first date, the one that goes well, comes the sudden onset of anxious doubt. Did it really go as well as all that? Or have you flipped through the runes but totally misread them?

Sometimes I have memories of events which cannot possibly be as I remember them. A picture comes to mind which includes me bodily – in other words I am looking at myself in whatever scenario it is – and clearly that cannot have been the way it was. These misremembered events usually take vaguely cinematic form – once, for instance, I hitchhiked in the back of a red pickup truck up the Interstate to San Francisco, and what I see in my mind’s eye when I recollect that day is a kind of helicopter shot of the truck travelling a hundred feet below with the small figures of me – and the girl I was with – in the back.

When I think back to the morning after that first evening out with Peggy, the camera is looking down from the ceiling in my rather tatty sublet on 2nd Avenue and 9th, and I am lying on my bed with my hands behind my head resting on the pillow. We are shooting through the ancient ceiling fan which, out of focus, is slicing through the picture in the foreground. Shades of Apocalypse Now perhaps, but this is a very different movie. Though awake, my eyes are closed and there is a dreamy expression on my face, implying such beatific happiness that, compared with me, Larry wouldn’t have been at the races.

London 1999

I tried. I really did. For the next few weeks the Polaroid of Peggy stayed locked away. I dropped it into the top left hand drawer of my office desk and turned the key. And whenever I was tempted to look at it – and dive into the warm waters of the past – I willed myself not to, or found some sort of distraction. I didn’t exactly take the Baden Powell option and nip off for a cold shower whenever I felt the blood rise, but it was that kind of thing. Denial – and the masochistic satisfaction one takes from it – were the order of the day. The trouble with denial is that the more you try to deny whatever it happens to be that you’re denying, the more you think about it. Which sort of defeats the object.

I pretended to throw myself into work. I really didn’t feel the genuine pull of it, the way I had pre-PP, but I made a decent fist of pretending that I did. I went to all the meetings I was asked to, and a few that I wasn’t. I manufactured a fake enthusiasm that I was sure looked just like the real thing. I made a point of randomly pitching up in the offices of all my people, not to keep them on their toes but to give them the impression that I was on mine. To all intents and purposes, I was back to being the relentlessly upbeat, company cheerleader that they expected me to be. Eeyore was out. Tigger was back in.

New York 1979

Is there anything more absurd, more destructive, more completely pointless, more self-defeating than jealousy? But, as motivational tools go, it’s unbeatable.

I adored Peggy from the first – within seconds of clapping eyes on her in the elevator in McDonnell Martin, I was utterly besotted. She had exactly the looks – black, glossy, wavy hair, long lashes, sweetheart lips, wry smile, but, above all, those dark, deep eyes – that, for some reason, I thought of as my ideal. (Curious that I ended up marrying a carrot-top. Although it’s true, that, at the time, I thought I loved her too.)

And then there was Peggy’s neat figure, her tight little body, her perky, pointy tits – it added up to just about the perfect package as far as I was concerned. But then, you might say, yes, but there are a million girls like that in New York and you probably wouldn’t be more than a few hundred thousand out.

Looks matter, you can’t deny it – when you first see someone across the room, what else is there? – but, once I knew her a little, it was much more than that. It was Peggy’s very particular take on life, her quiet independence, her sparky irreverence, her amused scepticism, her capacity to surprise, her sudden invention, her unreproducible Pegginess, that so entranced me. And let’s not forget that she laughed at my tee-shirt, got all my jokes, and ‘totally liked me’. That may have helped too.