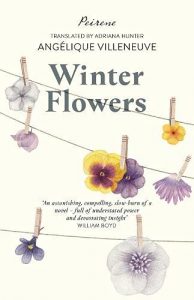

Published by Peirene Press 7 October 2021

180pp, paperback, £12

Reviewed by Rachel Hore

It is October 1918, the war is drawing to its close and Spanish flu haunts the backstreets of Paris. In her chilly tenement room young Jeanne Caillet raises her little daughter, Léonie, and labours long hours to assemble artificial flowers as she waits for her husband Toussaint to return from the front. But when one night he appears suddenly in the doorway, she is shocked to realize that he’s far from the man that he used to be. Their lives and their relationship will need to be refashioned.

This is an unusual novel about the effects of the Great War on the humblest people and especially the women left behind after their menfolk are called up. Through Jeanne’s tender viewpoint we experience their daily struggle to survive. In shining, delicate prose Villeneuve deftly evokes the suspense of waiting and enduring, Jeanne’s concern for Léonie, the constant eking out of the essentials of existence. The contrast of the shabbiness of her life with the beauty of the flowers that well-heeled women will buy is stark, but despite the scars her tools inflict, the petals’ poisonous dust and the pittance she earns, Jeanne is proud of her skills and the glorious results transfigure her surroundings in a way that’s almost spiritual. Tender, too, is her relationship with her neighbours, elderly spinster Mother Birot and grieving seamstress Sidonie. They all depend heavily on one another’s support.

Toussaint, at his homecoming on that freezing October night, seems to Jeanne to be taller than before, but it’s the mask he wears that both appals and fascinates her. He will not remove it, but it’s easy for Jeanne to gauge that the lower part of his face has been horribly disfigured. He can no longer speak. She’s not completely unprepared; she knows that he’s spent many months in hospital after being wounded. His father visited the hospital, but Toussaint wrote ordering Jeanne not to come and apart from one curtailed attempt she respected his wishes.

After his return, life in the tenement continues as usual, but now there are three to feed and all is made so much harder by the presence of this silent, traumatized stranger. Léonie thinks she has two fathers: the smiling soldier in a photograph and now this damaged newcomer. Through flashbacks we learn the facts of Toussant’s injury from flying shrapnel and how a skilled surgeon reconstructed his face using tissue from elsewhere on his body. For details of this groundbreaking procedure the author used accounts by the noted wartime surgeon Dr Hippolyte Morestin.

After many operations Toussaint could endure intervention no longer and discharged himself. He finds civilian life bewildering. Passers-by openly stare at him and make tactless comments. Dismayed, his wife aches for him. ‘The war burrowed into him… He’s a huge void, and Jeanne doesn’t know whether it can possibly be filled.’ Only very gradually do the couple begin to find a way back to one another.

Winter Flowers is not only the powerfully dramatized story of a relationship, but a poignant meditation on grief. Even before the war death stalked the Parisian backstreets. The Caillets lost their elder daughter to consumption. Sidonie mourned two husbands and five sons. Now, with the fighting, everyone they meet knows about loss. Most shocking is the apparent indifference of the establishment to their suffering. The speech at a ceremony where Jeanne accompanies Sidonie to collect a certificate to mark the death of Sidonie’s remaining son for his country feels such a travesty so that ‘Jeanne’s eyes are full of tears and bulging with anger.’

In recent years there has been a flood of novels set in the trenches, but not so many that focus on the quiet sufferings of the families left behind. This one is particularly special.