Published by Penguin August 6 2020

Published by Penguin August 6 2020

160pp, paperback, £11.63

Reviewed by Zoë Fairbairns

‘If a man have a house, he establish his right to live,’ thinks Galloway, aka Gallows, a young Trinidadian man who rents a bedsit in a down-at-heel London suburb where house prices start at around £20,000. (It’s the 1950s.) Gallows’ main financial asset is a five-pound note which he seems to have mislaid.

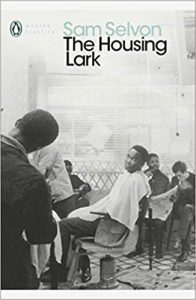

In The Housing Lark by the late Sam Selvon (first published in 1965, and now reissued as a Penguin Classic), Gallows joins forces with others similarly-placed, and they start saving up. Well, some of them do. They hand over the money to Battersby, a Barbadian who keeps the cash under his mattress. Well, some of it.

The triumphs and disappointments faced by these ‘boys’ (which is how the Trinidadian author/narrator refers to them, and how they often refer to each other) will be familiar to readers of Selvon’s other tragic-comic fictions about the lives of Windrush-generation West Indian immigrants to Britain, such as The Lonely Londoners (1956) and Ways of Sunlight (1957). Also familiar is Selvon’s vivid, evocative use of creolized English, which appears not only in spoken dialogue but also in the narrative – ‘he ain’t have no work and he living catch-as-catch-can’ – and in the narrator’s philosophical asides to his readers: ‘is so things happen in life.’

Here is the uneasy, exciting urban landscape – threatening yet beautiful – of the capital city of what these newcomers have been taught to think of as the Mother Country. Summers in London’s parks are flower-decked and glorious and full of temptations. Winters are bitter – ‘the basement door can’t open because snow pile up against it, or it fogging so much that he can’t see to walk up the steps.’

There’s ambivalence in the characters’ relationships with sometimes-hostile, sometimes-helpful ‘Englishers’ , and with each other. They give and receive solidarity and support, sometimes even taking the rap for each other’s crimes; they share food and give advice, but they don’t always remember to pay back loans. Suffering racism, they also dish it out, against people from the wrong part of the world, the wrong West Indian island.

Their longing for sex and romantic love is undermined by the savagery of their gender politics: the men stalk unknown women in the street for the pleasure of admiring the shapes of their bottoms, and conversational terms for a woman include ‘thing’, ‘craft’ ‘piece of skin’, and ‘stroke’. A man called Fitz recounts how he successfully discouraged ‘a thing from Croydon’ from putting pressure on him to marry her by giving her ‘ONE clout behind she head.’ Fitz, whose view is that ‘All woman want is blows to keep them quiet’, is later spotted married, raising a family, and sharing housework with a West Indian woman called Teena.

Teena is sceptical about the boys’ housing lark. ‘You know the distresses we have to go through, you know the arse black people see to get a roof over their heads in this country, and yet, the way you all behave is as if you haven’t a worry in the world… Just full your belly with rum and food… walk about, catch women, stand up by the market place talking a set of shit day in and day out. That is what you come to Brit’n to do? Fellars like you muddy the waters for West Indians who trying to live decent in the country.’

Some get the message and conduct serious discussions with estate agents about deposits and freeholds; others prefer to go an excursion to Hampton Court to pick up tips on how to live as a king in a palace with six wives.

A Jamaican musician called Harry Banjo, who reckons he is ‘the greatest calypsonian in town’, wins support for that view when an agent turns up to offer him a recording contract. Together with his sex-worker partner Jean, Harry looks as if he might afford a house. For everyone else the struggle continues long after this exuberant but dispiriting book concludes.

*

A later and more upbeat tale of property ownership within the Caribbean community in London can be found in Selvon’s Moses Ascending (1975), also available as a Penguin Classic.