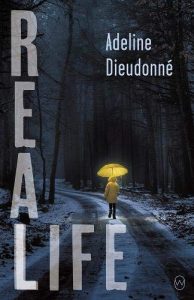

Published by World Editions 4 February 2020

266pp, paperback, £11.99

Reviewed by Alison Burns

Somewhat in the tradition of Emma Donoghue’s Room and Emily Ruskovitch’s Idaho, this dramatically horrific first novel addresses domestic abuse with a combination of cool-eyed, realistic frankness and quite remarkable imagery.

Adeline Dieudonneé’s unnamed young female narrator (whom I shall refer to as ‘N’) lives with her timid mother, her younger brother and their terrifying big-game-hunter father in a house where one room is ‘stuffed with carcasses’. Among these is a hyena so convincingly alive that she causes terror in anyone who looks into her eyes. ‘N’ can hear the hyena laughing.

‘N’ tells us in the opening pages that ‘when my mother got married, she wasn’t frightened yet.’ Not long afterwards comes the first of many staggering descriptions of domestic violence: ‘My mother always ended up on the floor, motionless. Like an empty pillowcase. After that, we knew we had a few weeks of calm ahead.’

When the father blows the head off the ice-cream man just as ‘N’ is stretching out her hand for her daily cone, ‘N’s life takes an even darker turn. Sam, at her side, is so traumatized by the incident that he is transformed into a robot, dead inside. When he turns eight, his father gives him a subscription to the shooting-range and he becomes violent himself, an animal-killer.

‘N’s reaction is to research the possibilities of time travel, so that she can go back in time, change the past, and thereby save everybody. As it happens, she is so precociously bright that a local science professor is persuaded to give her cut-price private lessons. All the knowledge in the world cannot alter the facts, and the novel ends as violently as it began.

‘N’s courage stays with the reader as she turns to face the second part of her life – ‘my real life’ – with a mixture of ‘stuff I had to forget’ and ‘stuff I had to hold on to’, including her brother’s smile.

In this fine translation, Dieudonné’s effortlessly readable novel packs a notable punch. The serious content is leavened by a fierce, glittering humour (Dieudonné also performs as a stand-up comedian). Published in France in late 2018, it has won many major prizes. One can see why.