Published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux 7 May 2019

Published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux 7 May 2019

288pp, hardback, $26

Reviewed by Elsbeth Lindner

Death and suffering, poverty and guilt suffuse – to the point of drowning – this unhappy first novel. Every departure from the main narrative thread – whether it’s the Challenger disaster or the Exxon Valdez oil spill – adds another overwhelming layer of mortality and horror to the story. But one crowning loss binds the tale, the death of a child and the suffocating layers of blame and responsibility that lay waste to the surviving family members.

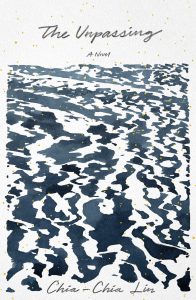

Narrated from the perspective of boy child Gavin, the novel traces the experiences of a family of Taiwanese immigrants living – if it can be called that – a life of borderline destitution in Alaska. The father was an engineer but now scrapes an income working on occasional building projects, the failure of one of which will tip the family even further into penury. The mother, who still reaches back to life in Taiwan, her family there and a rural idyll of coastal life, is bitter and at times demented. The four children divide into two boys – Gavin and his younger brother Natty – and two girls, eldest Pei-Pei and much younger Ruby.

Early on, Gavin returns from school with a fever and falls unconscious. When he awakes, many days later, Ruby is dead. And gone. All traces of her have been removed, except – it emerges later – for the urn containing her ashes, hidden on a high shelf in a wardrobe. Gavin had imported meningitis from school, but survived it himself. However the entire episode remains a family taboo, leaving all the members isolated in their own grief, most of all Gavin who blames himself for Ruby’s loss.

Atmospheric is scarcely an adequate term to describe the intensity of Lin’s evocation of the fabric of this family’s life. Clothing, terrible food, the flimsy home, its accumulated junk, the detritus in the attic – all of it is conveyed in near-palpable detail, piling on the bleakness of the novel’s mood. Even when rare good moments occur, like an evening spent in the home of a generous neighbor, Gavin is incapable of experiencing enjoyment. Instead, death lurks at every corner – in the attic where animal bones are found, in the forest where trees nearly fall on people, on the beach where a stranded whale almost succumbs.

Lin is undoubtedly a talented writer whose invocation of this group – their individual psychologies and combined tragedy – is achieved with numbing impact. Yet the book is impossibly burdened by its surfeit of bleakness and fixed tone. Fingers crossed that her second will offer more in the way of light and shade.