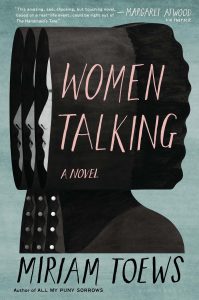

Published by Faber UK/ Bloomsbury US 2 April 2019

Published by Faber UK/ Bloomsbury US 2 April 2019

240 pp, hardback, $24

Reviewed by Elsbeth Lindner

The acknowledgements to award-winning novelist Toews’ latest, short work of fiction include the following statement: ‘I wish to acknowledge the girls and women in patriarchal, authoritarian (Mennonite and non-Mennonite) communities across the globe. Love and solidarity.’

Read her book – with its deft, brief title that can be read as disparagement or description – and you will swiftly understand why. The novel springs out of real events which took place between 2005 and 2009 in a remote Mennonite colony in Bolivia, where hundreds of girls and women would wake up drowsy, bleeding and in pain each morning. They were called devils by their (male) elders, blamed, accused. But later, the truth emerged, that men from their communities had been drugging and attacking them at night. Eight men were convicted in a Bolivian court in 2011 and given long prison sentences. But in 2013, similar assaults and abuses were still taking place in the colony.

On this ghastly foundation, Toews builds a tale which takes the form of a debate among a group of women, in a colony named Molotschna, about how they should respond to their rapes. The minutes of their conversation are recorded by a man – August, a teacher and the son of disgraced members of the colony, blameless in the attacks – whom they have invited to take notes. The women themselves cannot read or write, have never been anywhere, know nothing about the world, maps, art, the sea, technology. They are treated – they agree – as animals by the men who even at a young age command their existences. Their sons, once over the age of fifteen, have dominion over them.

Not all the women join the debate. Some accept the strict patriarchal conditions of their lives. But eight women, of varying ages and temperaments, are no longer able to tolerate the facts or implications of what has happened to them. Foremost is Ona, unmarried, but now pregnant after her own rape, who displays both sharp intelligence and warmth. August, a man whose history is far from domineering – his parents were cast out of the colony; he has been imprisoned; he harbors suicidal thoughts – is in love with her.

The women’s analysis of what has happened to them, their treatment, their own futures and their children’s, and above all how to absorb these events into their own sense of faith, fills most of the book’s pages, and might seem at times dry. But its territory is so horrific, so stark, so outrageous and contemporary that it magnetizes the reader. Toew’s sensitivity, lucidity, lyricism and wit ensure it.

August scribbles fast to keep up with their discussion, their efforts to decide – collectively – whether to stay or leave. Time is short, the men are away in town, raising money to bail out their brethren accused of the crimes. The tale becomes almost thriller-esque as the clock ticks down on the women’s freedom to meet, talk and act.

Compassion and comprehension crowd together as August stands in the hayloft, absorbing what he has witnessed and the feelings that remain. He also shares a late item which lays open the deep, pervasive nature of hypocrisy within the supposedly devout community. This last section of the novel, poetic and brave, leaves the reader quietly stunned.

Synthesizing complex and ancient arguments which also have bang-up-to-the-minute relevance, the book offers a crisp, immersive vision of oppression and survival. Read it as a manifesto for clear female thinking. And for a moving, positive view of the way forward.