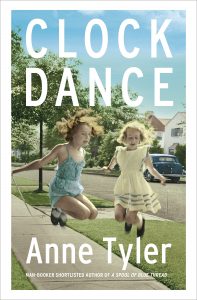

Published by Chatto & Windus/ Knopf US

Published by Chatto & Windus/ Knopf US

304pp, hbk, £18.99/$26.95

Reviewed by Alison Burns

The story of Willa Drake begins in 1967, on an ordinary suburban day in Lark City, Pennsylvania, when she is eleven years old. That evening, her mother disappears and, next day, Willa is left in charge of her kid sister, Elaine, while their father goes to work. Mrs Drake comes back quite soon, but the after-effects of this event will last a lifetime, engendering in Willa an expectation that it is the men in her life who will prove the more reliable.

Ten years on, Willa accepts a marriage proposal, interrupting her promising college studies to move to San Diego with her boyfriend, Derek. Twenty years on, now mother of two sons, she is abruptly widowed by a road accident.

What follows is the history of Willa’s bid for a quiet life that is also a caring one. In some ways, it is a tale of arrested development: in childhood, she had ‘felt like a watchful, wary adult housed in a little girl’s body’; ‘nowadays, paradoxically, it often seemed to her that from behind her adult face a child about eleven years old was still gazing out at the world.’ Her mother had always behaved wilfully, then sought forgiveness with disarming songs and smiles. Her husband had turned out to be rigid and unimaginative, quite unlike Willa’s kindly father. By the time she acquires a second husband, Peter, her optimism has quite gone: ‘Marriage was often a matter of dexterity, in Willa’s experience.’

So, when a call comes for her to rescue the nine-year-old daughter of her son Sean’s hospitalized ex-girlfriend, Willa goes – even though this means flying from Arizona to Baltimore, and dragging her reluctant husband with her. This journey pitches her into a chaotic new slice of family life which gives her an outlet and takes her mind off her own.

This latest novel by the ever-popular Tyler goes down like a cool, refreshing drink, but not much more. An average American wife, weakened by early experience and then browbeaten by the men in her life, gets a late chance to do good and be kind and be thanked for it. It is a portrait of quiet stoicism, of weathering (like the saguaro cactuses of which she is so fond), with too many dull passages and not quite enough of interest in either the central or the surrounding characters to keep readers pinned to their chairs.