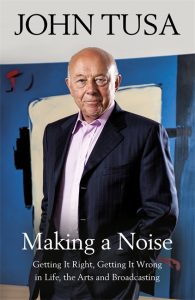

Getting it Right, Getting It Wrong in Life, Arts and Broadcasting

Getting it Right, Getting It Wrong in Life, Arts and Broadcasting

Published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson 22 February 2018

Reviewed by Jessica Mann

400pp, hardback, £25.00

In the final decades of the last century, the BBC World Service and the British Council, organizations designed to advertise British culture and values to the rest of the world, were both led by immigrants, men who were British by naturalization. ‘It’s because we know how lucky we are,’ John Tusa once told me. He, aged four, and his family (parents, older brother, younger sister) had arrived in England five weeks before the outbreak of World War II. Unlike the German Jews who came as dispossessed refugees, the Czeckoslovakian Tusas had a job and a home waiting for them. John’s father was to be Managing Director of the British branch of The Bata Shoe Company, so they moved into the newly built company town in Essex. John was transformed into an Englishman by going away to prep school aged six, and then on to public school, from which he won a scholarship to Trinity College Cambridge. ‘We acted, we studied, we partied, we flirted – those were the ingredients of our Cambridge lives in the late 1950s.’ He left with a first class degree, a wife (the historian Ann Tusa) and a BBC General Traineeship.

Tusa spent thirty-two years with the BBC. They were followed by a miserable few months as head of a Cambridge college, of which he gives an amusing but sad account, and a dozen years transforming the rather dismal Barbican into a busy, popular arts centre. In his seventies he became chairman of governors of London’s University of the Arts, and Chairman of the Clore Leadership programme. He has served on numerous other boards and committees, has continued to broadcast on radio and TV, and remains superhumanly energetic. In one typical year, 2012, the Tusas went to thirty-four exhibitions, thirty-eight concerts, seven theatres, twenty-seven parties and sixteen events or lectures. They gave thirty-eight dinner parties and went to thirty-nine, and made fifteen trips overseas. It is a remarkable story of commitment, enthusiasm and stamina.

Impressive though his later career has been, the most interesting part of Tusa’s story is the one hundred and fifty pages (the first sixty of them without mention of one single female) about his years on the staff of the BBC.

General Trainees acquired experience of everything to do with broadcasting, on both sides of the microphone and camera, and in radio and television. Tusa rose through the hidebound hierarchy to take charge of the BBC World Service. In this job, as in all those that followed, he was a reformer, uncompromising about the standards he rightly expected, and often at odds with his notional superiors. He is trenchantly critical of the changes made in the BBC under John Birt (Director General) and Marmaduke Hussey (Chairman of Governors,) particularly of the introduction of authoritarian management to an organization whose values were liberal, humanist and pluralist.

This is a fascinating memoir by a man with many happy memories and few regrets. One of them is that ‘I never thanked my parents for bringing us out of Czechoslovakia and into a land of wondrous opportunities where foreigners could flourish.’