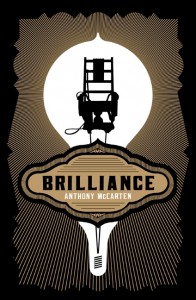

![mccarten102_v-gallery[7]](http://bookoxygen.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/mccarten102_v-gallery7.jpg) Published by Alma Books 12 April 2012

Published by Alma Books 12 April 2012

224 pp, hardback, £14.99

Reviewed by Elsbeth Lindner

Did inventor Thomas Edison and banker J.P. Morgan first meet in a bath in Saratoga Springs? Did Morgan possess, indeed cultivate ‘a postulated, bulbous magma of warty tissue with the texture of a cauliflower’ instead of a nose? Yes and yes if New Zealand novelist, playwright and film director Anthony McCarten’s affably ironic new novel is to be believed. His use of such eloquent details and imaginings add pleasing texture to the story – a parable on Wall Street’s tendency to co-opt and corrupt idealism – notably in the case of Edison, whose wives used Morse Code to counter his deafness; who existed on a mono-diet of milk; and who often appeared blind to the creative flair of others.

Given his experience of theatre, there’s also no surprise in McCarten’s inclination toward two-handed set-piece confrontations for the ongoing debate between his twin giants of history. Shuttling back and forth between the inventor’s cusp of creativity in 1878 and the wounded insularity of his octogenarian years in 1929, Edison is presented as Dr Faustus to ‘the world’s banker’ Morgan’s Mephistopheles who rescues him from debt, sets him up in business with the aim of bringing electricity first to Manhattan and then the whole USA, then deserts him for Westinghouse who has discovered cheaper manufacture of electric current.

While the central tussle of the book is Edison’s efforts to expand electric light into an affordable, widely available commodity, it’s his role in the development of the electric chair that carries the greater moral focus. The appalling development of this device, first tested on animals, including a wretched orangutan, and then used to execute a criminal, the murderer William Kemmler, is horrific for the scientist and the reader alike. It is this experience as much as any which destroys Edison’s last vestiges of optimism in his work and his sponsor. Efforts to be a businessman have drained the inventive brilliance from a person whose ambition was to do good and whose heroes were Michael Faraday, who turned down knighthoods, and Tom Paine.

Joining a growing group of fictional considerations of the role and effect of banking, Brilliance is short and simple in its didacticism, increasingly using Edison as a mouthpiece for the author’s insights, as in this comment made to an engineer during the gruesome electric chair experience: ‘I’ve got a new name for this chair: The Wall Street chair. This chair is meant for us, Harold, have no doubt, for you and for me – fool servants of a master whose only aim is to remove the last barriers holding greed at bay.’

In 1912, a year before his death, Morgan himself was cross-questioned during congressional hearings into the monopoly practices of various bankers and banks. By now he was reported to head an empire comprising 341 directorships controlling some $22 billion in resources and capitalization. The committee accused him of presiding over a banking system ‘that has seen this country exposed to two decades of brutal mergers and a carnival atmosphere on Wall Street which has triggered booms and busts in insane succession’ and pronounced him guilty of a kind of treason: Morgan and five other houses were found to be running the US economy for their own benefit, crushing anything that threatened their relentless growth.

Very evidently a case of plus ca change.

And as Morgan, a glass of Pommery in one hand, a redhead in the other, is glimpsed promising stupendous wealth – the Edison General Electric company, capitalized at a value of twelve million dollars – to the inventor, he simultaneously confirms to Edison money’s deathless grip on world-changing possibilities and the people who generate them: ‘You’re my best invention.’