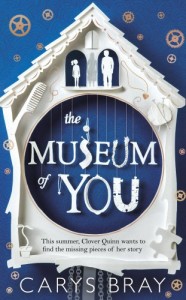

Published by Hutchinson 16 June 2016

Published by Hutchinson 16 June 2016

360pp, hardback, £12.99

Reviewed by Shirley Whiteside

Clover Quinn is twelve years old, and this is the first summer that her dad, Darren, has trusted her to stay at home alone during the school holidays. He is busy driving a bus from Southport to Liverpool and back, twice a day, worrying about his daughter, re-examining her every action, and wondering whether she is happy. Becky, Clover’s mother, died when her daughter was just weeks old so it has always been just the two of them, muddling along in the shadow of Becky. Darren never talks about his wife and his daughter isn’t sure how to ask about her.

Clover has been enjoying visits to various museums with the school and decides to curate her own exhibition, made up from Becky’s things which are still stored in the spare room. It is her way of getting to know her mother and a surprise for her father. Bray intersperses the narrative with Clover’s lists and plans for her exhibition which are delightfully detailed and charmingly naive. As Clover gathers specific items, she learns things about her mother that her father has kept secret and is torn between loyalty to him and wanting to know about Becky. Bray subtly shows how Clover is missing a vital piece of her life without being mawkish or overly sentimental.

Clover is an endearing character, sometimes wise beyond her years, sometimes just a little girl who wants a mum. She is bright and resourceful, full of ideas and questions about the world. She is a plucky girl and it is easy to both empathize with her loss and admire her determination to do something about it. There is a simplicity to her thinking that is in keeping with her tender years, the kind of childish logic that sadly doesn’t survive the teenage years.

At times, Darren seems less capable than his daughter, and if there is one criticism about the novel it is that Darren’s voice is not different enough from Clover’s. Darren has sacrificed his own dreams to care for his daughter, the child he and Becky didn’t even know was on the way. His world has become very limited, built around Clover and her happiness, and his deep-seated loneliness is gently inferred.

Bray’s supporting characters add colour and interest to the story, particularly the Quinn’s neighbour, Mrs Mackerel. She has a habit of speaking loudly and precisely when making a point, which Bray shows by capitalizing parts of her speech. She provides the light relief in the story, an interfering woman whose heart is in the right place. She often looks after Clover, a sort of substitute aunt or grandmother, and anchors the Quinns in their neighbourhood.

Bray has written a compassionate story about fathers and daughters, painting an affectionate picture of a girl approaching puberty who misses the mother she never knew. It is a charming read with surprising emotional depths.