Published by Thames and Hudson 1 September 2014

208pp, paperback, £16.95

Reviewed by Jessica Mann

On the day that Hitler’s army marched into Poland in 1939, 32- year-old Lee Miller was travelling round Europe with Roland Penrose. She had left America as a recalcitrant teenager, escaping to Paris where she lived with and learnt from the surrealist photographer Man Ray. Since then she had been a Vogue model, a professional photographer, and, for three years, the wife of a rich, posh Egyptian in Cairo. When Lee left him, in 1937, she went back to Paris where she met her life-time partner, the surrealist painter Roland Penrose.

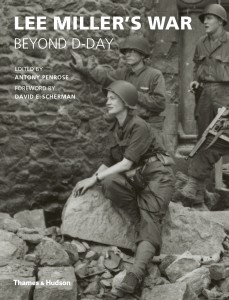

On the outbreak of war, Lee and Roland left Paris for Penrose’s home in London. Lee was an excellent journalist as well as a photographer. She no longer modeled for Vogue but the magazine published her articles and photos. She also made a photographic history of the Blitz and in 1944 managed to gain accreditation to the US forces as a war correspondent. ‘It is almost impossible today to conceive how difficult it was for a woman correspondent to get to the front,’ writes her colleague, David E. Scherman, in a long and interesting preface to this book. But through a series of lucky breaks Lee Miller did get to the front, and her first dispatch, from Normandy, described a field hospital for the wounded of Omaha Beach. More articles sent from France covered subjects as varied as the siege of St Malo and the novelist Colette.

As she travelled eastwards with American Army, Miller recorded the Alsace Campaign and – the subject for which her reporting is best remembered – her arrival at the concentration camp, Dachau, on the day after it had been liberated. Her photographs are mesmerizing and she describes her experiences in simple, unadorned and unaffected language which is a pleasure to read except when the horror of what she is describing wipes out any aesthetic satisfaction. There is no possible amusement in the description of Weimar’s citizens being forced to visit Buchenwald – within easy walking distance of the town – of which they all denied any knowledge. Her report from Dachau is pure horror. A few days later, Lee wrote a piece that began, ‘I was living in Hitler’s private apartment in Munich when his death was announced.’ Hitler’s apartment, and Eva Braun’s little house nearby, were unremarkable bourgeois homes, as described by Miller, with nothing to show they were owned by a monster. Berchtesgaden was more interesting in a macabre way, supplied with the best wines and champagnes of Europe, and with miles of huge grand rooms inside the mountain. Everybody hunted for souvenirs, and pocketed them. ‘Scattered over the breadth of the world, people are forever going to be shown a napkin ring or a pickle fork, supposedly used by Hitler,’ Lee wrote.

That scavenger hunt was Miller’s last fling from the front. Her war reports are signed off: ENDIT. TO MEMBERS OF STAFF OF VOGUE – HAPPY V.E.DAY!. She hardly ever spoke of the war again, her son writes, and tells us that she spent many of the post-war years in a misery of depression and alcohol abuse. As well as editing this volume, Antony Penrose has written his mother’s biography, and a book about his father Roland Penrose. It’s a spring that could run dry but it hasn’t yet; Lee Miller’s War is fascinating and informative, and also a very good read.