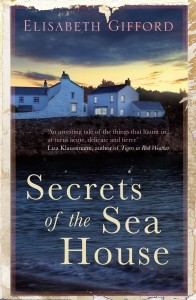

Published by Corvus, August 2013

Published by Corvus, August 2013

320pp, Trade Paperback, £12.99

Mass Market Paperback available January 2014 £7.99

Based on an actual nineteenth-century letter to The Times in which a Scottish clergyman claimed to have seen a mermaid, Secrets of the Sea House is an epic tale of loss and love. bookoxygen has ten copies of this arresting debut to give away to the first readers to contact us.

And now read on for a taster of Elizabeth Gifford’s compelling storytelling:

*

Prologue

My grandmother’s grandmother was a seal woman. She cast off her seal skin, fell in love with a fisherman, had his child, and then she left them. Sooner or later, seal people always go back to the sea.

At least, that’s the story that Mum used to tell me.

‘But is it true?’ I wanted to know.

‘It’s as true as you and me, Ruthie,’ she said. ‘There’re plenty of people up in the islands that come from the seal people.’

And later I used to think, of course, that’s what must have happened. That’s why she left me. She couldn’t resist going back to the water, because she was a Selkie.

For a long time, I liked to think that. Because it meant she might come back one day, and then I could go home.

Part One

Chapter 1

Ruth, 1992

I don’t think I had ever felt so piled with gifts as I did that first night we slept in the Sea House, or so excited. I was ready to get up and carry on with the painting there and then. It was completely dark, no slur of city light. I pressed the little light on the alarm. Two a.m.

I curled up closer to Michael’s long back. He was so solid in the darkness; his presence filled the room like a comfort. When I first met Michael, I thought he was too tall and elongated, a species I didn’t recognise. Then I realised that he was just how he should be, a sapling in a wood, his pale brown hair the colour of winter leaves. And right now, he was exhausted, completely dead to the world.

It had taken months of back-breaking and filthy work to get the old place scraped down to a blank canvas, and then we’d had to start the long haul of repairs ready for us to move in. The truth was that our bedroom and the half-finished kitchen were still the only inhabitable bits, but you could see from the proportions of the Georgian rooms with their elegant windows and carved fireplaces that one day the house was going to be beautiful.

I turned over again, far too awake for two in the morning, and also incredibly thirsty, probably because of the dubious cava from the Tarbert Co-op. I didn’t want to get a drink from the bedroom sink: we’d just cleared a dead bird from the tank feeding the upstairs taps.

It was icy when I slid outside the bedcovers. The fire in the bedroom grate had gone out. I went down the stairs as quietly as I could, feeling with my hands along the cold plaster where it was too dark to see.

Down in the kitchen, I filled a mug from the tap, and drank the water as I stared out at the dark shapes of the hills. A glassy moon, clear in the black sky. The room was flooded with monochrome shadows, but then the kitchen looked at its best in the dark. You could almost imagine that the humped shape in the corner was a new Aga rather than a builder’s old trestle covered with a cloth, a tiny Belling hot- plate and washing- up bowl on top.

Next to the window, the moonlight showed the pale squares of my noticeboard with its To Do lists for every room; snippets of cloth and paint cards; pictures of ideal rooms torn from magazines; a collage of how the Sea House was going to be – one day. I loved sitting at the rickety kitchen table updating the lists, adding and crossing off, enjoying the delicious feeling of our forever home finally rising up from the rather disgusting ruin we’d bought in the dead of winter.

I’d first seen the house by torchlight, running the pale light over the boarded-up windows, the walls cracked and streaked with green damp. We had to force the back door to get in. The air was thick with vegetal rot. Piles of filthy fleeces stacked up in the wreck of a kitchen. Crumbling dirt and debris everywhere. The air had felt so cold it sucked the heat from my face and hands.

I was ready to turn round and go back to London.

‘But don’t look at the mess,’ Michael said. ‘Think of it freshly painted, curtains at the kitchen windows, a nice big pine table here.’

Now, with the outside more or less weatherproofed, the rats evicted and the holes in the roof remedied, the debris swept away, and after hours and hours of plastering and painting, we were finally in – and it was possible to imagine that one day, instead of a chilly building site, the Sea House would feel like a real home.

And always the next thought, the one that seemed impossible. When the house was completely ready, we’d come in through the front door, and I’d be holding a small, warm weight, a little sleeping face in a nest of soft shawls. Our child.

I avoided glancing down to the bottom of the noticeboard and the scruffy wad of bills still to be paid. Felt the niggle of worry stir in my stomach.

I tipped the mug up and put it on the draining board – carefully, as the sink was a bit loose from the wall, propped up with some wood off cuts. The flagstones were freezing and starting to make my feet hurt. My shoulders felt pinched by the cold.

There was hardly any moonlight as I crossed the hall to go back upstairs. The new floorboards felt unpleasantly gritty under my bare feet and a freezing draught was coming up from the missing skirting board, bringing with it a clayey odour. I shivered and made for a pool of moonlight on the lower banisters. I put my hand out to take the newel post and felt the cold of the gloss paint under my palm.

That’s when I saw it: a quick blur of movement like a tiny wing caught from the corner of my eye. I saw a hand descending on the newel post just after mine.

I froze. A sudden, painful pricking of blood in my feet, the smell of clay sharp in my nostrils, every instinct primed to get out of there. She was so close, so palpably present, I thought she would appear in front of me. I couldn’t breathe. My heart was gabbling so hard I thought it was going to give out.

And then she was gone. The air relaxed.

I ran up those stairs, the door to our room half ajar just as I had left it. I got back into bed with a thump and lay close to Michael. He murmured but didn’t wake.

I stared into the dark. What on earth had just happened? Some delay in the messages from my eye to my brain. Some silly trick of the mind half roused from sleep had sent me into a stupid panic. Eventually my heart slowed to normal and I’d almost talked myself down, was almost drifting off when I woke up once more, very alert. I opened my eyes onto the darkness. Then why had it felt so intensely real, as if someone else was there in the hallway, standing beside me so closely that for a moment I wasn’t sure who I was?

The fear was beginning to seep back in. I felt sick from fatigue, but there was nothing I could do; I stayed alert and awake, listening out to the minute sounds of a silent house, all my senses still primed.

I could hear the waves breaking along the shore like soft breaths. I got up and wrapped a blanket from the chair round my shoulders, went to the window and lifted the wax blind. The moon was completely round in the blackness. There were bright lines of its phosphorescence along the waves, continuously moving through the darkness and then disappearing.

I watched them for a while. After that I felt calmer. Eventually, I got some sleep.

When Michael came in with two mugs of coffee next morning, the sun was already strong through the blinds.

‘The wood’s being delivered this morning,’ he said, picking out a T-shirt and giving it a sniff. He worked his arms into it. ‘We might have a floor in the sea room today.’

He sat on the bed, making the mattress bounce, and pulled on his grubby jeans from the day before. I had to cradle my coffee so that it didn’t spill on the new duvet. It had an oily bitter smell. I wondered if the jar of Nescafé had gone stale. I put the coffee to one side on the orange box that was covered in a new tea towel for elegance.

‘Donny’s coming to help pull up the rest of the old boards. Although we’re going to dig a channel in the earth underneath to lay a cable first.’

‘I’ll come down and help,’ I said.

‘I thought you were going to finish your drawings.’

He leaned over and bashed my chin with a quick kiss. His long, slim arms looked different, the muscles and veins more prominent. He’d worked so hard to get us out of the caravan. He’d hated the little bed that didn’t let him stretch out, but I’d got to quite like living in the shelter of the dunes, right next to the deserted beaches and the wide Atlantic rollers that towered up like molten glass in the blue winter air. I was glad that the Sea House was almost as close to the water, just the other side of the dunes, where the green machair broke into sandy waves of undulating silver marram grass. And then the beginning of the wide, flat beaches.

Michael stood up, stretched his long torso and combed his hands through his curly hair. I think the thing that made me fall in love with Michael was the way he stooped to listen to me because he was so tall, as if he really wanted to hear what I was saying; and he was so kind and willowy, his mop of wiry, fair hair like a medieval angel in a picture. He pulled on a jumper, then his grimy overalls. He smiled, slapped his legs, ready to get started.

‘So, Donny’ll be here in half an hour.’

‘I’m getting up. It’s just, I didn’t sleep well.’

‘Yeah, I know. I’m constantly thinking about the next thing to

do, seeing us open, the first guests rolling up. And I still can’t believe we live in this house, in this fantastic place.’

I could hear him whistling as he went downstairs.

I got the fire going again in the grate and had a horrible cold wash in the sink in the corner of the bedroom. I pulled on my jeans and a flannel shirt, feeling guilty that it was Michael who was doing all the back-breaking work, while I got to sit in the only good room and draw lizards. The book was on reptile neurology and I’d just started the last chapter: ‘The Brain and Nervous System of Podarcis erhardii, commonly known as Erhard’s Wall Lizard’. Michael had got used to sleeping in a room with the dry aquarium and its lizard family, and the faint acrid smell of waxy chrysalises that collected at the bottom of the tank.

I lifted the insulation wadding and looked through the side of the lizard tank to see how they were getting on; immediately, a flick of a tail and a scuttle; the two lizards flashed into a different position and then froze. The thing about lizards is you can never tame them. They have a very small, very ancient brain that operates on one principle: survival. They spend their whole lives on high alert, listening out for danger, scanning their surroundings with their lizard eyes, their toe pads picking up every vibration in the earth, ready to send back one message to the brain cortex: flee, flee now. They don’t consider, or think; they simply reach a certain overload in feedback criteria and then run. They are sleek little bundles of vigilant self-preservation with an evolutionary strategy so effective, you can find a lizard brain tucked inside every developed species.

I pushed back the sleeve of my jumper and carefully lowered my hand into the glass tank. There was a flicker and they both scuttled to the other end in a flurry of sand and tiny sideways straggle legs. But there was nowhere else for them to go. I slowly moved my hand towards the corner; another quick scuffle, and my hand closed round one of them. I could feel the little whip of muscle working inside my palm and the scratching of its back legs.

I held the chloroform bottle against my chest with the top of my arm and unscrewed the top. Then I covered the opening with a wad of cotton wool and tipped it over with my free hand. I held the damp cotton over the struggling lizard. Waited till it stopped. I put the lid back on the bottle, and sat down at the desk. The lizard was lying across the piece of card, its arms and legs something between a minute plucked chicken and a cartoon frog in its anthropomorphic arms-up pose. I picked up the scalpel and started to slit along the belly skin, ready to map out the nerves.

I realized that the banging and splintering from downstairs had stopped. I have an amazing ability to sit through noise and not notice it once I begin to work, but the sudden silence was unsettling. Not even the sound of digging. Something’s come up, I thought, and went downstairs with my arms folded. I only hoped it wasn’t more problems. Michael’s father had lent us enough to get the manse ready to take our first bed and breakfasters, but we needed to be open as soon as possible if we were to keep up the payments.

I made my way down through the hallway, crossing my arms across my chest against the chill. Down in the sea room, every one of the square sash windows was filled with views of the Atlantic so that the place always felt more sea than room. Michael and Donny were standing thigh deep among the floor joists, looking at something. When Michael saw me coming in he didn’t look pleased.

‘What is it?’ I asked. ‘Just tell me the worst. Is it dry rot?’

Donny looked upset and serious. Michael was white under his summer tan and the grime from ripping up the old wood. It was freezing in there. There was a fusty smell of rot and damp.

‘I don’t want you to look,’ he said. ‘You won’t like it.’

‘What is it? Oh God, not another rat.’ I walked round the edge of the walls where there were still some floorboards down and then lowered myself into the floor space between the joists. The floor was damp and sandy and littered with dirt and debris. Michael and Donny were standing one each side of a small dark-brown box, or rather a little metal trunk that was rusted away in places. It had evidently just been dug up from the sandy soil.

The lid was open.

I squeezed next to Michael so that he had to hold on to the joist behind him.

‘Don’t,’ he said.

I squatted down and looked inside. The earth smelled very sour and close there. I could see a jumble of tiny bones mixed in with a nest of disintegrating woollen material. There was some kind of symmetry to them; a tiny round skull, like a rabbit or a cat. The bones had a yellowish tinge, scoured clean by beetles and other organisms that had got into the trunk as it rusted, probably over many years. I wondered why someone had buried a cat under the house. Then I tipped my head sideways, frowned.

This was no family pet or small animal. No, this was the skull of a human baby, but everything so tiny that it must have been born either very underweight, or premature. My eyes traced along the arm bone and then down the bones of one of the legs.

Something was wrong. Where was the other leg? I shuffled closer, and noted the strange thickness of the single leg bone, the long central indentation along its length, and then I realized that it wasn’t so much that any of the bones were missing but that both legs had been fused into one solid mass, the feet barely there and oddly splayed out like tiny appendages.

My heart missed a beat. I couldn’t believe what I was looking at.

This sounds like an amazing read would love a copy 🙂

Applying for free copy of this book

ooh this is intriguing-would love to read it if I’m lucky..