Published by Rippple Books 1 October 2013

Published by Rippple Books 1 October 2013

Rippple Books – yes, 3 p’s, standing for ‘producer to public publishing’ is a publisher of challenging English-language books based in Germany.

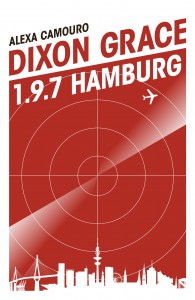

One of its first titles is a political thriller featuring Dixon Grace, an Australian of Indian descent living in Hamburg. She shares a flat with her boyfriend and teaches English to local workers. She’s beautiful, smart and stylish. And she’s a dangerous international spy – or is she?

An inspiring, audacious heroine; a wittier, edgier, female James Bond delivering supercool one-liners and sassy comebacks, Dixon skilfully dodges her way through the maze of international intelligence out to snare her.

Now sample this fast-paced international page-turner for yourself.

*

Landeskriminalamt,Hamburg

15 September, 2011, 8:16am

The room is rectangular. Not very big, but it feels big because there’s just one table and two chairs. Plastic chairs in black, a metal table with a vinyl covering that looks sticky, that’s stained with the rings of coffee cups and water glasses.

The usual standard stuff in a room that’s mostly off-limits. Nothing fancy or comfortable or aesthetically pleasing.

Function over form,’ she says softly, looking down at the floor and seeing small holes where a chair – a special chair – could be bolted down.

She’s sitting in one of the black plastic chairs, slouching really, arms folded, and wearing clothes thrown over her baggy sleeping underwear; her sleeping costume, as Astrid would call it.

They hadn’t allowed her to get dressed. No bra. No shoes. Not even a chance for a morning pee.

What a way to wake up, she thinks. But where was Ben? Why hadn’t he been there when they came, when they stormed in with helmets on and automatic weapons raised? Oh, but he’ll be pissed all right. They kicked the door down.

This makes her smile, then she shakes her head.

Come on, she tells herself. The room. Focus on the room. It’s about four metres by three by three. So, an area of twelve square, volume of thirty-six cubic. Like the business class section of a plane, roomy and high-ceilinged. No. The ceiling’s too high. Because all those plane designers are little people, building claustrophobic cabins with tight seats and limited leg room, big enough for them but no one else. Kids maybe.

She knows this. She toured the interiors department, had a class with six Hobbit-sized cabin designers. For the first lesson, they even sat in two lines of three, one behind the other, chairs close together and shoulders almost touching, like they were on a flight somewhere. She laughs a little.

Stop it, she says to herself. The room. Concentrate. That mirror on the wall. They’re watching.

She decides the room is more swimming pool than airplane interior. An upside-down pool, replete with greyish-blue walls and ametallic, chemical smell. Chlorine dried by the sun; the backyard pool of a foreclosed house left to rot in a Melbourne suburb. The result of a financial bubble bursting, some sub-division contracting company going bankrupt, the houses half-built, with all those young couples now riddled with debt and living with their parents again, or bunking in a caravan in front of a friend’s house. The Australian dream gone horribly wrong.

That’s better, she thinks. Run with that. Feel the sadness and loss. The anger. All those people drowning in an ocean of debt, the way I’m drowning in this upside-down pool. All those people who went after something and failed, or had it taken away from them, wrestled away at gun-point, woken at dawn by half a dozen guys in riot gear who shout ‘Keine Bewegung’ when you’re still asleep, then cuff you and haul you away. And you can’t shout or protest because your mouth is still furry with sleep and you’re somewhere between dreamland and reality and you’d been having the nicest dream of empty beaches and softly peeling waves and gulls squawking and you could almost taste the salt of the water on your tongue and that’s the place where you most want to be.

Not here. Not in this room. Not even in this country.

Having lost the focus, she rubs at her wrists, to try again. She wonders why they cuffed her, like she’s some criminal mastermind they chased halfway across Europe; some massive deployment that required the coordination of police forces from several countries. Car chases, jumping out of trains at high speed, false IDs, disguises, Swiss bank accounts, that sort of thing.

And she wonders why they said nothing, except ‘Keine Bewegung.’ Didn’t say what she’s done, just barged in and dragged her from the bed. Some slight act of mercy meant she had a millisecond to throw on pants and a shirt.

Then cuffed.

At least they didn’t use those plastic handcuffs, she thinks. The ones which cut off the circulation and leave red welts that take years to disappear, making people think you tried to commit suicide once.

So, that works in their favour. Old-fashioned, dangling, S&M cuffs. And they weren’t rough, either. Another plus. They were just … brisk. Yeah, that’s it. Brisk. In a hurry, as if someone was timing them. A training drill.

She shakes her head. ‘This must be some kind of mistake,’ she says to the mirror.

God, I look awful, she thinks, running her hands through her stilsleep-matted hair.

She hates the stringy feel of the blonde dye job. And it needs to be re-dyed.

She runs her hands through it again, nearly pulling the hair from its roots. What it needs, she thinks, is a double wash and a hundred brush strokes. Double wash and a hundred brush strokes. The way mum had done it. Brush out all the crap, brush the blonde away, get back to the roots. Such beautiful hair, until she cut it all off and left. She starts to cry. She focuses harder. The memories, the loss, all the things she missed out on, things she didn’t get.

Real tears come and she doesn’t wipe them away. They run down her cheeks and drip onto her shirt.

The door opens. She sits up straight and gathers herself.

‘Morgen.’

He’s a big man, and he seems to fill the room, breathing in deeply and sucking the air out of it. He’s a bit paunchy, heavy all over, but not fat. Solid. She wonders if he was an athlete when he was younger. He has that filled out look of a guy who played a lot of sport, then was happy to stop going to training, to let himself go. Now, he’s kilos in three figures. A muscular lump.

He’s dressed in new cheap clothes, the kind of stuff that hangs on massive racks at discount department stores. Stuff that’s sorted by colour and always on sale. Clothes made of plastic. On him, they don’t fit exactly right, and the colours don’t suit him, certainly not that yellow pullover. It makes her think someone else bought the clothes for him, or ordered them from an online catalogue. A wife dressing her husband the way she wants him to look.

He closes the door, then stands at the table, almost readying himself to sit down, like he doesn’t quite trust the structural integrity of that little plastic chair. He has a thin blue dossier in his right hand and some kind of book or magazine. He places both on the table. She sees it’s a book of logic problems, with a pen hooked into the cover. There’s a folded corner, half-way through, marking the page and puzzle he’s up to. Nearly every page has been dog-eared, making the top of the book fan open slightly.

The man sits down slowly. The chair slides on the floor a little, but holds.

‘Wie geht’s?’ he asks.

‘What am I doing here? What’s going on?’

‘Moment. Moment.’

He zips down the ill-fitting yellow pullover and plucks a pair of glasses from the pocket of his shirt. He has big hands, meaty and swollen, with a couple of the knuckles bulging; fingers once dislocated and not quite put back into place, maybe snapping them in himself and getting it wrong.

Heroin addict hands, she thinks. But he’s no addict.

She does not want to be touched by those hands.

He puts his glasses on, pushes the book of logic problems somewhat reluctantly aside and flips open the dossier. He smoothes his moustache with a massive index finger as he reads, or pretends to read. His moustache is perfectly trimmed to the corners of his mouth.

‘Australierin,’ he says.

‘Pardon?’

‘You are from Australia.’

‘Yes.’

He looks up, thick brown eyebrows almost knitted together. ‘Sie sprechen Deutsch, oder?’

‘What?’

‘Do you speak German?’

‘Sorry. No.’

‘Why not?’ he asks, checking the dossier again. A finger taps against the paper. ‘You are here since nearly two years.’

‘Well, excuse me,’ she says. ‘I never got the chance to start. And every time I tried, people spoke back to me in English.’

‘Yes. Blame us for that. It is the fault of us that you cannot speak our language.’

‘Uh-huh. You got that right.’

He grunts and goes back to the dossier. She sees his eyes move to the book of logic problems.

‘You do them in English?’

‘Hmm.’

‘That’s a good way to practice. For learning, I mean.’

‘I am willing to work at a new language,’ he says, without looking up.

‘Yeah, but English is the world’s most illogical language. There’s all these rules, then all these exceptions to the rules.’

‘I do not understand.’

‘I’m rambling. Sorry.’ She gestures at the book, happy to have something to talk about, a focus. ‘But those are tricky, because of the double negatives and the double meanings.’

He checks the dossier and looks up. ‘You are English teacher.’

‘And that’s also why I never learned German. I speak English all day.’

‘Is no excuse.’

‘I guess not. Have I been arrested by the language police?’

‘That is not funny.’ He spreads his arms in order to signify the room they’re in, and says, ‘All this, is no joke.’

‘I know.’

‘And, Miss Dixon, do you know why you are here?’

She laughs.

This makes him angry. ‘Why are you laughing?’

‘I’m sorry. It’s just so old fashioned, to call someone Miss with their first name. So Victorian, or deep south America a hundred years ago.’

‘I do not follow.’

‘Ah, I get it. You think Dixon’s my surname.’

‘That is how it is written here. Grace Dixon.’

‘It’s wrong,’ she says. ‘Why do you people always get my name wrong? It’s Dixon Grace.’

‘No. It is Grace Dixon. Because it is here in the file.’

She laughs incredulously. ‘Yeah. Sure. You’re freaking file is right and I’m wrong. I told the git in the foreign office several times that Grace is my surname and still he put it down like this. Same with my bank card, and my insurance card. Why would you all think you’d know my name better than me? Such arrogance.’

The man crosses his big forearms tightly, like an oversized kid in a huff. ‘This is not a good start.’

‘I guess I got hauled out of the wrong side of the bed this morning.’

‘Miss Grace.’

‘You can call me Dixon.’

‘I will not. Miss Grace, do you know why you are here?’

‘I asked you the same question,’ she says. ‘I don’t have a clue, logic or otherwise.’

‘This is very serious.’

‘I agree with you on that. It’s definitely a serious room, with some serious-looking bolt holes in the floor, and a serious mirror which some serious people are probably looking through.’ She waves at them. ‘And it’s definitely a serious matter when you arrest someone for no reason.’

‘We have a reason.’

‘What is it?’

‘A source.’

‘To hell with that,’ she says. ‘I don’t want to hear any of it. I want to contact my embassy. Now.’

‘We contacted them.’

‘That’s great, but I want to contact them. There is no reason for me to be here. I’ve led the life of a saint in Germany.’

‘Please. Calm down.’

‘I’m calm. I’m seeing nothing but yellow sun. Maybe on a different day with you, I’d be seeing red.’

He tugs self-consciously at the yellow pullover, zipping it up, then down, then rubbing his forehead and retreating to the dossier. He lets out a loud sigh.

‘My name is Kriminaloberkommissar Gerd Schultze. I work in LKA5.’

‘Ell car aah phoonph?’

‘Landeskriminalamt.’

‘Is that where I am?’

‘Yes,’ Schultze says. ‘Wirtschaftskriminalität.’

‘Love the compound nouns, but it’s all Greek to me.’

‘You should learn German then,’ he shouts. Then he controls himself, clearly aware there are people watching and judging. He even gives the mirror a brief, apologetic glance. ‘My department is responsible for economic crime.

‘Like insider trading, that sort of stuff?’

‘Sometimes, yes.’

She shrugs. ‘I don’t have any shares. And I paid all my taxes last year. This year too. Paying ahead like a good citizen. I have an accountant who organized that for me.’

‘Very smart. The tax system here is complex.’ Schultze checks the dossier again. ‘Especially when you are Selbstständig.’

‘Right, a freelancer. It was the only visa I could get. But in the end, I didn’t get it. They gave it to someone called Grace Dixon. Never met her. Maybe she’s the one you want.’

A smile stretches below Schultze’s moustache, a thin line of relative exasperation that breaks long parentheses at each corner of his mouth, bracketing the hair. ‘I read that Australians like to joke,’ he says, sounding very informed. ‘But this is serious. Can you be serious?’

‘Sure. Of course. I’ve got nothing but respect for the police. I’ve done nothing wrong and I’ve got no idea why I’m here.’ She speaks to the mirror. ‘Can we make this quick? I’ve got classes to teach.’

‘Ahem, the crime is Wirtschaftsdelikt,’ Schultze says formally. ‘Economic spying.’

‘Economic spying? Do you mean corporate espionage?’

Schultze snaps his fingers. ‘That is it. I made a direct translation.’

‘And you’re sure you’ve got the right person?’

‘Our source named you.’

Dixon crosses her arms and sits back. ‘Who was that exactly?’

‘I cannot say.’

‘Ben?’

Schultze looks at the dossier.

‘Because he wasn’t there when the cavalry arrived,’ Dixon says. ‘He must’ve left when I was asleep. Rather convenient, don’t you think?’

‘We need to stay on the topic. I will ask you some questions and you will answer them.’

‘I wouldn’t believe a word he says.’

‘Who?’

‘Ben. Benjamin Steckdorf. He called this in, didn’t he?’

‘No, he did not,’ Schultze says, and Dixon decides that he’s lying.

‘Now, my questions.’

‘Let’s go. Get it over with. Are you recording this?’

‘We are.’

‘Filming it too?’ She runs her hands through her hair and checks herself in the mirror. ‘I look terrible. That’s really brutal, you know, to pull someone out of bed before they’ve even had a shower and brushed their teeth. Do you treat your wife like this? Are you married, Gerd?’

‘Kriminaloberkommissar Schultze.’

She watches Schultze play with the wedding ring, pushing it up to his big knuckle and twirling it a few times.

‘You’ll never get that off,’ she says. ‘I hope you love your wife because that marriage is forever. Or you’ll have to chop your finger off. What did you do to your fingers anyway? They look wrecked.’

‘Handball,’ he says, looking at them. ‘But we must talk about you.’

‘That’s big here, isn’t it? I have some friends who play basketball and I went to watch a game. They always have to play on these rubber floors. They’re so dusty, the players slip all over the place and twist their ankles. It’s dangerous.’

‘They are handball courts, not basketball courts.’

‘That’s right. Because a real basketball court is made of wood.’

‘Look, we must focus on why you are here.’

She shifts in the chair. ‘I’m sorry, Gerd. I’m cranky when I get up too early. When I don’t get my morning shower and coffee. I’m a girl who likes routine.’

Schultze claps his hands together once. ‘Right. Miss Grace, what do you know about planes?’

‘Airplanes?’ she says, shrugging. ‘They fly, sometimes crash. They never have enough leg room, not even for little old me. And they’re an awful thing to sit in for the twenty-four hour trip toAustralia.’

‘You teach at the … uh … at the big plane company across theElbe.’

‘You mean Flussair?’

He grimaces, and nods once.

‘You can’t say the name?’

‘No.’

‘Hah.’ In a mock serious tone, ‘Yes, Mr Schultze. I teach at the big plane company on the other side of the river. Isn’t that well said? No one will ever know.’

‘When did you start there?’

‘Almost a year ago. My language school organizes classes there.” Sarcastically, ‘Can I say the name of the school?’

Schultze checks the dossier. ‘Multilinga.’

‘Why can we say that name and not Flussair?’

‘Because I say so.’

‘Hah. You don’t scare me,’ Dixon says roughly. She just keeps herself from jumping up and attacking Schultze. Not to hurt him, but to show him that she could take him down, easily.

‘I only want answers. And facts.’

Dixon nods slowly. ‘They know already, don’t they? And they want to keep their name out of the press, out of the police files. Keep everything nice and clean.’

‘I am right. You know a lot about this.’

‘And so I should. According to you, I’m a corporate spy.’

‘You admit it.’

More Aussie humour, I’m afraid. You’ve got the wrong Dixon Grace, or Grace Dixon, or whoever. The wrong girl.’

Schultze clasps his fingers together, seeming to restrain himself. Dixonwishes he would get up and try something. He looks like he wants to.

Come on, lard bucket, she thinks. Try me.

Schultze taps the table three times with that combined fist, which is the size of a small pumpkin.

‘Grace Treya Dixon’ he says, reading from the dossier. ‘Sorry. DixonTreya Grace. Born in Narooma, New South Wales. Female. Twenty-six years old.’

‘Wow. You must fly through those logic problems.’

The very faint sound of a woman laughing makesDixonlook at the mirror.

‘What kind of name is Treya?’

‘It’s my middle name. Would you like to call me Miss Treya?’

‘You are very rude,’ Schultze says. ‘This name, are you a native?’

‘A what?’

‘A native from Australia.’

‘Do you mean an Aborigine?’

‘Yes.’ Nodding with embarrassment and avoiding Dixon’s eyes, ‘Yes.’

‘I’m not. It’s Indian. Sanskrit, actually. It means walking in three paths.’

‘You are Indian,’ Schultze says, pouncing on the fact. He takes the pen from his logic problems book and makes a note in the file. The pen seems to get lost in his big hand.

‘My grandmother is, but I’m Australian. And that means I get to call my embassy to ask for support.’

‘Ah,’ a big index finger in the air, and a moustache smiling, ‘but you say you did nothing wrong.’

‘Which is precisely why I want to call my embassy, so I can get out of here and get on with my life.’

‘Please, calm yourself.’

She takes a deep breath. She knows she’s pushing it, knows she has to, up to a certain point. She also knows that she has rights.

‘You don’t seem to think this is a mistake,’ she says.

Schultze has something of a hopeless look on his face, like he’s powerless to the facts. ‘I only know what I know,’ he declares. ‘Now, you came to Germany in January last year. May I ask why?’

‘Obviously to steal secrets from plane company X.’ She sighs and lowers her voice. ‘I have a friend here. We met at school in Narooma. She was an exchange student.’

‘Astrid Thielen.’

‘How do you know that?’

‘It is in the file.’

‘So you got her name right.’

‘You registered at her apartment,’ Schultze says, also reading out the date and address.

‘Yeah, so I stayed with her for a bit, then I took a room in a shared flat in the Portuguese Quarter. It was really cramped. Bathroom was a closet. It was awful.’

‘And you moved in with Benjamin Steckdorf in January of this year.’

‘Why are you repeating this? ’Dixon asks. ‘You’re not exactly the world’s greatest interrogator.’

‘I wish to establish the facts.’

‘For a crime I have nothing to do with?’

The door opens and a woman enters.