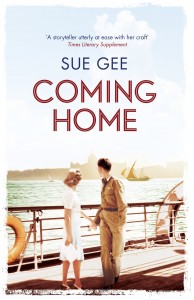

Published by Headline Review 1 August 2013

Published by Headline Review 1 August 2013

432 pages, hardback, £19.99

A new novel from Sue Gee is a cause for celebration. This cherishable writer, author of nine previous novels, one of which, The Mysteries of Glass, was long-listed for the Orange Prize, receives wide acclaim for the warmth and empathy of her fictions.

Her latest novel spans three decades of a British family’s life, through end of empire to the shifting sands of the 1960s. Now sample it for yourself.

*

Prelude

1947

She was writing her last letter home in the café of the Grand Hotel. Though an awning shaded the window from the morning sun, the room was splashed here and there with points of light: on the china, on the snowy tablecloths, and the waiters’ crisp starched shirts; against teak panelling blackened with years of cigarette and pipe smoke. And as people lit up now, in uniforms and mufti, tapping out a Player’s, tamping down a wad of tobacco, smoke drifted through the crowded room, to and fro between the little tables, over the tarnished gilt mirror on the wall, up through the slow-moving paddles of the ceiling fan. Darling Parent-Birds . . .

Through the glass-panelled door she could see all the comings and goings in the marble foyer, and hear, as it opened and closed, the shouts for a luggage wallah, for a taxi to the harbour, where troop ships were moving out of the dazzling Bombay waters, sounding the siren, taking home the last British officers of the Indian Army. In less than an hour, she’d be on one of them.

Darling Parent-Birds, We’ve got here! What a journey . . .

All the way down from Tulsipore, a place on the Nepal border as far from civilization as you could get.

When they’d first arrived last autumn, setting up house as newlyweds in the old wooden bungalow, Will drove her out to the jungle by moonlight, holding her hand as they walked along the paths. Enormous vines hung from the trees. She and Will made out the shapes of roosting birds, the dark silhouette of a sleeping monkey.

‘I saw a tiger drinking here once,’ he told her, as they came to the glinting bed of a stream. ‘Stayed up all night in a tree to wait for him. The most beautiful creature I’d ever seen.’ He drew her closer.

‘Until I met you, of course.’

‘You didn’t shoot him,’ she said, when they’d finished kissing.

‘Shoot him? Of course not.’

But he’d shot a panther once, he told her, as they walked back to the car. ‘That was different – he was taking the villagers’ goats, prowling around the compound at night. They asked me to get rid of him, and the headman took some jolly good photos afterwards, with my Brownie. I’ve got the head and skin in store: he’ll come back to England with us one day.’

When he went off to work, riding out to the sugar cane fields at daybreak, leaving her with cook, bearer and his old black Labrador, she lay in a green cane chair in the shade, slept inside in the afternoons, listening to the creak of the punkah, dreaming of his return. We’re so in love, she wrote in her diary. Can it really have happened to me? At last?

Each evening they had their drinks on the veranda, watching the sun go down behind the distant peaks of the Himalaya, the fall of night so swift, so sudden – and then those stars, a vast shower of silver in the inky sky. Will knew them all, had watched stars and birds and animals all his life. Their bearer brought out supper, stood waiting quietly. As soon as they’d finished, they went to bed – We just can’t keep our hands off one another! she told her diary. In a couple of months she was pregnant.

And then all this began, she wrote to her parents now, in her corner of the café. Ex-Indian Army officers were entitled to a free passage home, but wives must be paid for – and no woman more than four months pregnant was allowed on board. By the time we heard that, I was already three! So we had to get weaving – one of Will’s favourite expressions! – in order to buy my ticket.

It had taken a week of train journeys: to Cawnpore, then Delhi, then Bombay. In Cawnpore, headquarters of the Sutherland plantation, they said goodbye to everyone at the Club. One or two are staying on after Independence– they can’t imagine living in England now. But Will’s been here so long, he can’t wait to come home. And I can’t wait for you to meet him!

She broke off, looked out across the smoky room. Where was he?

‘You stay there, my darling,’ he’d said, when he’d tipped the luggage wallah. The room off the foyer was heaped with cases.

Their trunks were already on board in the hold – stuffed to the brim, and including the panther! Then he was off, striding away to the little white house on the pier again, where he’d been told at Army HQ in Delhi he should buy her ticket. But yesterday it was shut up tight – I only hope it’s open now, or we’re stranded!

A huge urn hissed on the counter.

‘More tea, memsahib?’ said the old waiter suddenly at her side.

Perhaps someone wanted her table, but she wasn’t going to move.

‘No, thank you.’ She still had only a phrase or two of Hindi.

Will had been fluent for years.

‘Tik hai?’ he called, every time he came home.

‘Tik hai.’ She held out her arms. ‘All’s well.’

The waiter moved to the next table, the door to the foyer swung open and shut, officers came and went. But still no Will. Of course, he was saving taxi money until they left together – one special last night in the Grand has almost broken the bank! – and it was quite a walk to the harbour. And she thought of her first sight of it, eighteen months ago, leaning out on the ship’s rail beneath the awning as they came steaming in: the bright cotton saris of the women selling chai and knick-knacks along the wall, the dusty palms swaying in the hot sea breeze.

You were so right to tell me to come here, she wrote to her parents, and as she turned the thin blue page of airmail paper, she saw herself, with the other RWVS girls, Judy and Ann and poor darling Rhoda, laughing all through the voyage: over their G & Ts, over the games of deck quoits, and flirtations with handsome young officers returning from leave – men looked so gorgeous in khaki! Out for an adventure at the end of the war, getting over her broken heart at last.

India! India had saved her.

It had saved Will, too, from a deadly London insurance office.

When his father died in ’34 – a heart attack at the Rectory breakfast table, what an awful thing – he’d left his mother and sister in Norfolk, upped sticks, and come out on his own adventure.

Wealthy Uncle Arthur had given him a chance.

‘And you know, I took to it at once,’ he’d said, telling her all about himself on their first date, as men did. They were having drinks in the Club in Delhi, she with her curls springing out from under her RWVS cap, he meltingly handsome in uniform.

‘I found the Europeans a dreadfully stuffy lot,’ he went on – oh, how he went on! – over his ice-cold beer. ‘But the young Hindi chaps – we got on like a house on fire.’

He’d picked up Hindustani in no time, and quickly been promoted, spending ten years with Sutherlands: riding out to district plantations, supervising the growers, buying their cane. ‘Must have ridden about ten thousand miles overall,’ he said, lighting his pipe.

‘Had a super horse.’ Then the war came, and he’d joined the Rajputana Rifles, one of the best regiments in the Indian Army.

‘One of the best in the world!’ He became a weapons trainer, rose to major, fought in North Africa, was wounded at Alamein, almost lost a leg . . .

‘Now what about you?’ he said at last, as men always did, though you could usually tell, as they leaned forward, and asked if you wanted another drink, that they weren’t all that interested in what you actually did.

Which was just as well, because one way and another she hadn’t done much with her life, so far. Before the war – well, lots of boyfriends, of course, and in between she’d tried all sorts of things: doctor’s receptionist, kennel maid, nursing home assistant . . . Then: then she’d thought she should do something serious, get a proper nursing training, and that had ended in— Oh, she couldn’t bear to think about that time.

As for the war – she’d done her bit, pushed a lot of planes about in the Ops Room with the WAAF, but frankly it was fun with the officers in the evenings, which was what the war had really been about. Until one of them broke her heart. ‘Well,’ she said, with a little laugh, perched on the edge of her chair. Waiters hurried to and fro between the potted palms, glasses chinked on brass trays, people up at the bar were roaring with laughter. The atmosphere in here was terrific, everyone letting go now the war was over at last.

‘Well?’ he asked, giving her what was suddenly the sweetest, truest smile, and suddenly she couldn’t look back at him, couldn’t give one of her flirtatious little looks, could only sit gazing at the bubbles of tonic, fizzing away in her glass.

Gosh, she’d been miles away.

I’d better finish, she scribbled. Will’s bound to be back in a minute! And she thought of them all in an English spring, Father at one end of the breakfast table, pushing his specs up his nose as

Mother, at the other end, listened to her news.

Soon the British flag will run down all over the country – Will says it’s bound to happen, and he thinks it’s right. I’m sure Father has been following it all in the paper.

Vivie would be making toast, and Hugo swinging his legs, stroking the cat beneath the table and longing to get back to his train set.

There’s just a little matter of a job, of course, but he’s so competent, he’s bound to find something.

‘All I want to do is look after you for the rest of my life,’ he’d said, as they kissed one another to death in the back of a Delhi taxi. ‘Marry me, marry me.’

Such an outdoor chap, of course – he’s talking about farming.

I do love farms! Anyway – I’ll post this on the way out, and I’ll see you soon!

And she signed it with all her love, as always, but not as Felicity, but with her new nickname. I know you find it hard to get used to, but once Will said, ‘Flo, Flo, I love you so,’ I’m afraid that that was it!

She licked the envelope. She wasn’t Felicity Davies any more, either. Mrs William Sutherland, she wrote on the back. And just The Grand Hotel, Bombay, because they didn’t have an address now.

She put down the letter, and looked across the room. In the huge gilt-framed mirror she saw herself amidst the hurrying waiters, amidst all the officers and wives: a woman in her thirties, newly married, expecting her first child. Happiness and pregnancy lit her up, she knew it, though she’d been told she was pretty all her life. ‘You’re very bad for a man, Junior,’ gorgeous wicked Guy had told her, trying to get her into bed, as they all did. Then he went back to his wife. She hadn’t even known he was married. But now – now all that was in the past, and she was a different person.

Was it true? She looked at herself through the drifts of smoke, and saw an officer at a nearby table look back at her, in the mirror.

She’d been so used to men’s glances: now she turned quickly away.

Had flirtatious, impetuous, scatter-brained, oh-so-emotional Felicity really gone for ever? Felicity Davies. Mrs William Sutherland. Flo. Could a new name make you a new person? There were so many things she wanted to leave behind.

No more weeping. No more feeling an utter fool. She was going to make something of herself at last.

And as she thought of the fun she’d had, writing her letters home, and of all her Indian diaries – notebook after notebook from the bazaars, packed away in her trunk – it came to her.

One day she would write about her time here, and how it had changed her life. She tucked the letter into her bag, and pushed back her chair. The baby kicked. And then the glass-panelled door swung open, and there was Will, striding in at last, making his way through the tables towards her.

‘My darling. Still no ticket wallah – I waited for ages. But we can get it on board, apparently, from the purser’s office. A chap’s just told me.’ He helped her to her feet. ‘So sorry I’ve made you wait all this time.’

‘Doesn’t matter,’ she said, and her heart went flippity-flop as he kissed her. ‘I’ve been writing away. And the baby’s just kicked again.’

And he said that was splendid, he was so glad, and then he paid the astonishing bill, and went to get their cases, pointing out to the luggage wallah the green leather one he’d given her as a wedding present, and his old brown army kitbag. Both were stencilled with their initials: he’d organized that, as he had everything else.

A born organizer! she’d written to Vivie, telling her all their wedding plans. Getting married in Delhi within three weeks of meeting – I can hardly believe it! And yes, I know it’s the right thing. Promise.

She followed him out across the cool marble floor. ‘On you go,’ he told her, as a boy in white jacket bid sahib and memsahib goodbye, and opened the great wooden door to the street. ‘That’s it.’ And she walked through, and he swung the bags after her, and out into the sun.