Published by Linen Press 28 October 2013

Published by Linen Press 28 October 2013

256pp, paperback, £9.99

Reviewed by Alison Coles

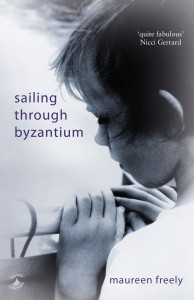

The cover of Sailing Through Byzantium is exquisite, an evocative black and white photo image of a young girl, her thumb bandaged, lost in her own thoughts and clutching the rail of the ship. It reminded me of the cover of the late Lorna Sage’s Bad Blood, sharing the same quality of vulnerability of the young child, but where Sage’s book was a memoir, Sailing Through Byzantium is a novel, albeit with something of the rhythm of a memoir. It is told from the point of view of a bewildered nine-year-old, Mimi, who, while living inIstanbul with her family, is told a Byzantine web of sometimes well meaning lies by adults and is on a mission to figure out the truth of life at all costs. The family forms part of the colourful, polyglot community in Istanbul and the book is set during the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962. With their very existence under daily threat, the family see Russian tankers pass through the Bosphorus from their apartment window.

This bohemian group plans a grand gesture of defiance in the face of nuclear war – they will still be singing at the end of the world. And so it is that they plan a party at one minute past President Kennedy’s midnight deadline to President Khrushchev. With Mimi hiding under the grand piano, Grace , her mother, sings at the end of the world party, her haunting blues voice rendering Stormy Weather unforgettable to all who hear her.

Grace is a little remote from Mimi, and prefers beauty and fantasy in the face of awkward facts. She survived her hard childhood in 1930s Brooklyn partly by dint of her passion for opera and the blues, and wove fantasies she came to believe herself, particularly the warning that it was still a man’s world and if she wanted to spread her wings and fly, then never trust a man’s words, only his actions. ‘Make sure you are on the ship with him.’ This was the story the grown-up Grace passed on to Mimi, filling her mind with excitement and the beauty of faraway strange places to which she eventually took her.

It was for her mother that Mimi tried to make sense of it all, listening to Radio Moscow, spying on the sailors on the Felix Dzerzhinsky on their trip to Egypt, writing in invisible ink, sketching all she saw. But there was always a painful gap between what she yearned for and what she received.

When Mimi returns 50 years later she is still trying to make sense of what she lived through as a child, still trying to connect with her mother’s grace and beauty which are as elusive as ever. She asks herself, ‘I wonder what thread in me was severed that night? Why I left this great room so determined never to return?’ Mimi tells us too that she misses, ‘Believing in metaphors that always seemed to have an exact meaning. Most of all, I miss believing in my mother’s stories.’

Freely tellingly dedicates the book, ‘To my mother: keeper of the mysteries’.

Sailing Through Byzantium is Freely’s seventh novel and her third set in Istanbul, the city where she grew up. It is a hugely poetic book, heavy with metaphor, the women’s names redolent of meaning – Sibel, Grace, Hope – and it felt right and agreeable to have the omission of Mimi’s siblings’ voices, details of some biographical information which would have otherwise weighed heavily on the perfect rhythm of the novel.

The wide cast of characters themselves though were uneven in their power of conviction. Most were colourful and self-absorbed in their own dramas. Mimi herself I was drawn to, a compellingly attractive character whose own belief in herself never wavered. But Grace seems more fey more than mysterious, so absent from herself, and from her daughter. And as it was her young intention to see the world, an intention she made manifest, she did not then seem to be fully in the centre of her own experience. The emotional disconnect with her atheist nuclear physicist father is convincing with her reference throughout to ‘my father’ without giving him his name.

What Freely does succinctly and memorably, though, is conjure up the picture of Turkey in the 1960s – how odd, how romantic and how mysterious it must have seemed to a young child from distant America. And what a gift to the reader.