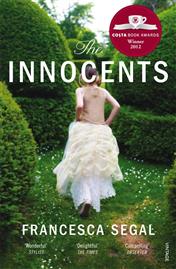

Winner of the Costa First Novel Award

Winner of the Costa First Novel Award

Published by Vintage paperbacks 10 January 2013

368pp, paperback, £7.99

Reviewed by Sara Maitland

This is an elegant little novel and a real delight to read. It is also surprisingly moving – surprising because in some ways it ticks too many boxes for the book club market and ought to feel contrived and formulaic. (Take a community about which there is some curiosity but not too much knowledge in the general novel-reading population – if it uses a few words of a foreign language, or a strong regional dialect, so much the better; centre on a single ‘point of view character’ (first or third person, but strongly voiced); feed in a great deal of social detail, especially about food and clothes; devise an ethical dilemma arising out of a conflict between the mores of the target community and those of the likely readers; create an unexpected plot crisis which forces the central character into decision; resolve the situation, one way or the other, leaving some regret about the consequent loss.)

The Innocents demonstrates all of the above elements. Adam, a clever young lawyer and a member of the North London Jewish community, has just become engaged to his childhood sweetheart, Rachel, to the delight of both their families. They have both entered freely into the relationship and look forward to the smooth, almost inevitable, continuance of their safe and pleasant lives. But the fact of being formally engaged, of having made his choice, unsettles Adam – he dreams of how it might be to be otherwise, to break away from this close and deeply supportive, even infantilizing, society – where he works for his future father-in-law and still knows most of the individuals he was in primary school with, while Rachel is perfectly, almost smugly, content with her destiny.

At this moment Rachel’s renegade cousin Ellie – glamorous, libertine and highly vulnerable – appears from New York, possibly seeking to be re-united with her roots; possibly seeking refuge from a scandalous relationship and its media worthy outcome. She and Adam are strongly drawn to each other, not only sexually (although that is a powerful element) but emotionally – both had lost a parent under tragic circumstances, both slightly resent their dependence on Rachel’s family.

Adam and Rachel do get married, but afterwards he still hankers after (or deeply loves, or somewhere in between) Ellie. Eventually he decides to leave Rachel and London. At this moment a double crisis asserts its control over the plot: his father-in-law’s firm has invested all its assets, including the pension fund, in a broker, also a member of the community, who goes bankrupt; all their lives are threatened.

Adam does not run off to Paris as planned, but stays to work on the attempts to salvage whatever is possible. At the same instant Ziva, Rachel and Ellie’s redoubtable grandmother, has a life-threatening heart attack. Then Adam, still planning to leave with Ellie, discovers that Rachel is pregnant. . . By this point it is hardly a ‘spoiler’ to relate that Ellie, who learns about the baby before Adam does, makes the decision for him by leaving; he is reunited with Rachel.

This fairly trite plot however is redeemed – partly by very lovely, sensitive and acute writing; partly by the truly intriguing and perceptive social detail; partly be the fact that Adam is a genuinely persuasive and likeable character; and partly by a discreet but clever irony: the novel is an updated version of the 1920 Pulitzer-prize-winning The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton – the parallels are close, but given how deeply anti-Semitic the New York social elite was in that period, transplanting the story to a Jewish community is not only clever, it also gives a wider, more general point of reference, in quite a subtle way.

Mainly the book works because the dilemma is a real one and has a far wider emotional reach than simply a bit of fictionalized anthropology. Adam’s choice is not really the traditional fictional one between marriage and passion; between two women – wife and mistress. It is genuinely a choice between community values and self-fulfilment. Both are fairly presented as desirable and good, and it is clear that Adam is free to choose which happiness he desires most, and why. Anyone who lives, or who grew-up, in any close-knit, deeply settled community knows that to stay within the boundaries (wider than one might imagine from outside as the novel makes clear) does genuinely offer a richness of life – it is not conventional cowardice that keeps people ‘at home’ in these worlds.

This really is a novel that addresses, with subtlety, two lovely ways of being and accepts that no one can have both. By the end the readers are fully aware that for Adam the outcome is neither a victory nor a tragedy, it is a choice.

The Innocents is not a demanding or a challenging read, but it is a deeply pleasing one.