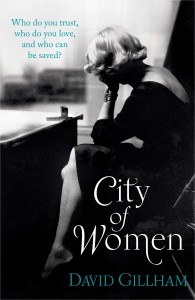

Published by Fig Tree 31 January 2013

Published by Fig Tree 31 January 2013

400pp, paperback, £12.99

Reviewed by Rachel Hore

Several key events of David Gillham’s debut take place in the suitable darkness of a cinema, for his tale of World War Two Berlin is as grim, monochrome and claustrophobic as any noir thriller, with a narrative that unfolds like a script in short, tautly written scenes. It’s 1943, and after a year’s respite, British bombers are once more hammering the city. Out in Russia, Hitler’s forces face shocking, unexpected defeat, yet the Nazis urge the German people to hold out longer, to make more sacrifices, promising the war will be won. Meanwhile the Gestapo sweeps through Berlin, rounding up Jews and their families and despatching them to the camps. With all able-bodied men taken up by the army, the German capital is left a city of women.

Sigrid Schroëder, in her late twenties, appears every inch a dutiful soldier’s wife, working as an office clerk, scraping together the rations and caring for her interfering mother-in-law. But underneath she feels trapped and unhappy, bitter at her childlessness and haunted by memories of a passionate affair with a married Jewish man named Egon who has since disappeared in the wartime chaos. It’s only when she’s drawn into the activities of another occupant of her apartment block that she begins to revive. Ericha Kohl, a 19-year-old mother’s help neglectful of her duties, is not all she seems either. Sigrid helps her escape the interest of a Gestapo agent one evening and soon finds herself complicit in an operation to hide Jews – in particular a woman and her two daughters she’s sure are her lover’s family. As the story unfolds and her involvement grows the odds stack higher that she and Ericha will be discovered.

There is little place given to outright heroism in this novel. Gillham’s interests lie in the moral shades of grey, which he explores so vigorously in the story that the explanatory Author’s Note at the end is redundant. Sigrid is an ordinary woman trying to survive and be happy, but is stirred to act by love, pity and a streak of human decency. Ericha is angrier, more rebellious in her resistance, but hard, less compassionate as a person. As a whole Gillham’s cast are a flavoursome but unprepossessing lot. Even some of those rescued show little gratitude. The neighbours are bad-tempered and selfish, some nurse appalling secrets, most are stretched to their utmost merely trying to exist.

It’s dangerous for Sigrid to trust anyone: she witnesses how merely offending a neighbour can lead to denouncement and arrest for unpatriotic behaviour. Yet the most unlikely people prove trustworthy. Some of these expect something in return for their aid – money or sex – but at least they help. Sometimes a character is made to bear too much freight, such as the Nazi officer’s pregnant wife who lives opposite. With her blonde plaits and her Heil Hitlers, she’s a textbook Aryan, but her secrets include Jewish ancestry, a lesbian half-sister, who briefly shelters Egon, and a destructive, alcoholic mother. Others of the cast use such violent or criminal methods to save lives that the moral compass’s needle swings wildly free.

City of Women paints a convincingly bleak picture of Berlin on its knees. Scene after scene burns into the reader’s memory – shards of bombed out buildings; vignettes, seen through bus windows, of victims beaten or bundled into trucks; desperate lovemaking in grimy hotel rooms; the desolate eyes of the people Ericha hides. I can already imagine the film.