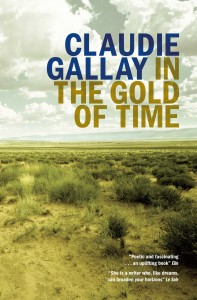

Translated by Alison Anderson

Published by MacLehose Press 10 January 2013

304 pp, paperback, £12.99

Reviewed by Catherine Jones

The relationship between a father of seven-year-old twins and Alice Berthier, an elderly woman who lives with her mute sister, Clemence, begins when he leaves a bag of strawberries behind after a chance meeting.

Staying for the summer at the family’s holiday home in Normandy, the nameless narrator becomes drawn into the world of Alice through her off-beat questions – ‘Wouldn’t you like to have an ocean named after you?’ – and gradual revelations of the past, sparked by a collection of sacred ceremonial masks once belonging to the Hopi, a tribe of Native Americans from Arizona, and said to contain their spirit.

In a breathless, telegraphic style – playing on the passing of time, and memories lost and regained – the narrative moves between the contemporary family’s summer by the sea near Dieppe and the story related by Alice, who visited Arizona as a child with her father, a photographer, who knew Andre Breton and other such notables of the age.

Alice starts to confer attention on her new companion, commenting on his appearance, sleeping habits, and marriage as he spends increasing amount of time with her, while his wife, Anna, becomes more distant.

‘Who is that woman you’re seeing?’ Anna asks. ‘I don’t want to know her name. Just what it is that she gives you that I don’t.’

A woman of silences and stubbornness, Alice – ‘Sometimes I kill them,’ she says of spiders, ‘but today I don’t feel like it. It’s because you’re here, it’s your presence’ – is tricky but the truth about the past, and her father’s interaction with the tribal Sun Chief, are gradually revealed.

The book flits along, with Alice revisiting beginnings in an attempt to fill the ‘the vastness of the unnameable’, while the narrator struggles to understand the gaps in his marriage.

Their relationship has the fitful closeness of burgeoning lovers – ‘I feel like killing you when you’re like this,’ she tells him – in an atmosphere laced with food and secrets and the power of speaking out.

Erratic and filmic, threaded with art and literature, the contemporary strand of this novel seems the most effective – the exchange of emotion and information between different generations, an elderly woman recalling her youth and a modern-day father learning how to live by returning to the past.