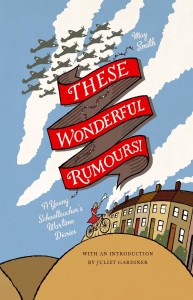

Published by Virago 1 November 2012

Published by Virago 1 November 2012

416pp, hardback, 14.99

Reviewed by Jessica Mann

This book is a diary kept during the Second World War by a middle-class woman in her twenties. It opens in 1938 and continues until January 1946 when the writer’s first baby has just been born. The final entry ends with the words, ‘Baby as good as gold.’ Now that baby has edited and published his mother’s diaries and they are introduced in an informative foreword by the historian Juliet Gardiner who explains that the great appeal of May Smith’s diary is that it enables us to understand the mundaneness as well as the drama of life in the 1940s. The life described here is certainly mundane. Dramatic events occur all around – evacuees arrive, bombs explode, aeroplanes fall out of the sky – but excitement is blunted by the writer’s matter-of-factness. Nothing evokes as much emotion as a disastrous perm or the purchase of a new coat.

At Christmas 1938, when the diary begins, May Smith is 25. She lives in Swadlincote, Derbyshire, with her mother and father. Her grandparents and an aunt live along the road. May is a primary school teacher, with a class of forty or more children. One can’t help sympathizing with her regular moans at the beginning of a new term: ‘School – oh, awful! Plod grimly through the day.’ The job is almost an interruption to her real life in which she is an enthusiastic tennis player, something of a flirt and an assiduous reader, moving from a new instalment of E.M.Delafield’s Diary of a Provincial Lady in the magazine Time and Tide to Simenon, Dickens, P.G.Wodehouse and Charles Morgan (the only one whose work May expects to survive.)

May has two principal interests. Boys are the first. Several are courting her, in particular the trusty Doug, who sends the family invaluable food parcels containing eggs or vegetables or even a cockerel, and the less reliable Freddie, who is more elusive, ringing up to invite May to the flicks or for a game of tennis, but is in the habit of turning up at the last minute, or – worse – cancelling appointments.

May’s other preoccupation is her appearance. Her frequently permed hair is always too frizzy or too straight; her salary won’t run to new underwear so she sews her own bra. Every winter she wants a new coat, every summer a new frock . Sometimes they are made for her by a local dressmaker, and turn out disappointing, sometimes she takes a bus into Derby or Burton and chooses something ready-made in a department store. All these activities carry on for the six years of the war. So do descriptions of meat and two veg meals of a kind that many people claim were non-existent under rationing.

War diaries are read for descriptions of warlike experiences, and May Smith had plenty of them, spending many a night in the basement listening to bombs explode, distributing child evacuees or queueing for whatever commodity the shop had suddenly come by. But the historical value of this book is in its demonstration that life on the home front was not necessarily as different, deprived or as dangerous as one usually supposes. May demonstrates that the English really did as they were exhorted, ‘carry on’. The trouble is that however authentic this account of ordinary life may be, it is inevitably very repetitive, so like all published diaries this one would be better read intermittently. Reviewers have to take one gulp, and I found it rather a stodgy one.