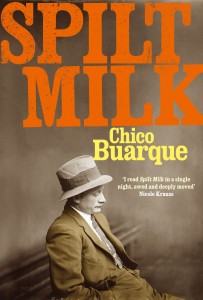

Published by Atlantic Books 1 October 2012

192pp, hardback, £12.99

Reviewed by Shirley Whiteside

One-hundred-year-old Eulalio Assumpção lies dying in a public hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Confused and lonely, he recounts the story of his life to his daughter, his great-great-grandson, passing nurses, even to the ceiling, desperate to pass on his experiences before he dies.

What immediately impresses is the strong, distinctive voice of Eulalio. He is a character who demands and sustains close attention as his memories range from his affluent childhood to the poverty of his extreme old age. A descendant of Portuguese invaders, Eulalio keeps referring back to his ancestors, one of whom was made a Baron, who anchor his recollections. He remembers holidays in Europe every summer with his womanizing father, the large house and farm out in Botafogo, and the chalet-style house on the beach front at Copacabana. This was long before the concrete and high rises of modern Rio swallowed up the individual homes and gardens along the beach.

Eulalio incurred his rather snobbish mother’s displeasure by falling in love and marrying the cinnamon-skinned Mathilde. His mother had wanted him to marry a pale-skinned girl from a good family. Eulalio’s happiness with Mathilde is short lived as she disappears from his life after giving birth to their daughter, Maria. Each time he tells the story of his marriage he gives a different reason for her departure and what became of her. These are amongst his most moving memories, his love for his wife and the pain of missing her all too apparent.

Eulalio’s daughter has a son, who has a son, who has a son, and he often can’t remember which is which. His great-great-grandson, a drug dealer, pays for his medical care as all Eulalio’s inherited money has been squandered by Maria and her con-men boyfriends. But with the youngest Eulalio in prison, Eulalio senior’s place in hospital is under threat.

What is most endearing about the old man is his lack of self pity. He tells the story of his descent into penury factually which only serves to make it more touching and authentic. He can be imperious and challenging, often reminding hospital workers of his distinguished lineage, but he never slides into self-indulgence. Overall, Eulalio emerges as a rather likeable and heroic family man.

This is a confident piece of work from Buarque who is a well-known singer, composer, dramatist, and poet as well as a novelist in his native Brazil. Eulalio’s voice remains consistent and through his rambling reminiscences Buarque conjures a dramatic picture of the old man’s life. Though some incidents are retold with different details, Buarque never loses control of his material and the fragments coalesce into compelling narrative. The translation by Alison Entrekin is smooth and polished – there are no jarring inconsistencies – and Eulalio’s often formal language suits a man born into a well-to-do family in the nineteenth century.

Buarque takes the reader through hundreds of years of Brazilian history, from the Portuguese invaders of the sixteenth century to the republic of the early twentieth century and dictatorships of the century’s middle years. However, outside of Portugal, the history of Brazil is not widely known in Europe. Some factual information about the period covered by Eulalio’s story would help put the events portrayed into context and make this fascinating novel even more enjoyable.