Published by MacLeHose Press Quercus 2 August 2012

Published by MacLeHose Press Quercus 2 August 2012

224pp, hardback, £14.99

Reviewed by Catherine Jones

Nobody is happy. Nobody has a voice. Set in the grim landscape of Finland’s economic downturn, here’s a tirade against modern-day spin and where it’s got us – graduates in welfare queues, intimidating youths in city parks, and Salme Malmikunnas’s three adult children in various stages of quiet despair. (Her fourth child died young after cycling into a well.)

Elderly narrator Salme, who made a living from a traditional yarn and button business, mainly communicates with her children through epigrams on the back of postcards, and her husband doesn’t speak at all – a man with a temper but mute since an undisclosed family tragedy.

When an author in need of a story offers money to Salme, she starts talking and doesn’t stop. ‘The author’ wants to make fiction of her truth – for contradiction, as one character ponders, is ‘salt’ and ‘without contradiction, life has no flavours’ – and in any event, Salme needs the money for another undisclosed reason.

Meanwhile, the lives of her children – products of a society rife with transient ‘operations management’ jobs – are woven through her own observations on the bitter joys of motherhood, delivered with the terse emotion of a generation no longer daring to consider itself the backbone of the nation.

Salme is apparently unaware one of her children finds meals by loitering in the food halls of department stores to load up on freebie tidbits, another is on the verge of a breakdown (or self discovery), and a third takes to shoplifting a meat pie and a hoodie.

‘Do you like to resist change?’ her eldest, Helena, is asked in the office.

‘I like to resist stupidity,’ Helena replies, fed up to the gills with meetings, committees and ‘memoranda strategy working groups’.

A range of disenfranchized characters act as vehicles to take a pop at aspects of contemporary life – the man who started life as ‘a no-one, with nothing, from nowhere’ obsessing over his Audi, the public outpouring of grief in response to the death of Princess Diana, and the everyday worship of celebrity.

‘How could they say they loved people they didn’t know, who spoke, sang, danced, played sports and wrote well!’ asks Salme’s daughter, Maija, of her peers. ‘The people on television and in the magazines…they jumped, slimy, from magazine to magazine croaking the same thing, their eyes wet with their own excellence’.

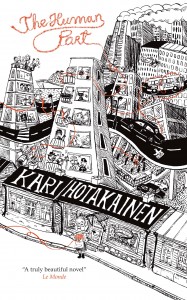

Might this novel be a cry for forgotten virtues – the likes of kindness, imagination and creativity – in a money-mad, status-obsessed world, all of it drawn together in something resembling the crazily-doodled metropolis on the book’s cover?

‘Take time for yourself,’ says a sign in the window of a chemist. The author appears to be offering a wry entreaty to find peace in the mayhem, and the wherewithal to know oneself – even if you have to find your way there in a car with Clint Eastwood’s voice on the G.P.S..