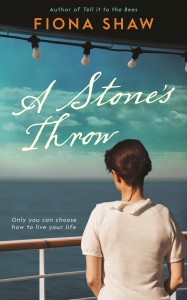

Published by Serpent’s Tail 5 April 2012

240pp, trade paperback, £11.99

Reviewed by Elsbeth Lindner

Divided into five elemental sections, Shaw’s fourth novel opens with ‘Ice’, seven pages so economically charged with emotional and visual clarity that the reader is instantly pitched into its glimmering world.

It’s a near impossible act to follow and indeed as the story settles into ‘Water’, then ‘Earth’ and the rest of the sequence, it inescapably falls into a less haunting, more recognizable rhythm. ‘Ice’s’ dark fairytale of a terse father and trusting, then truant son trudging through snowy countryside is replaced with a woman’s story more than a decade later, as Meg Bryan embarks on a sea voyage from England to Africa during World War II, to join the fiancé only recently met and accepted, not for love but to escape a mother’s neediness.

Now the book joins forces with two currently vogueish content streams: the floating collection of survivor-in-a-lifeboat tales such as Charlotte Rogan’s The Lifeboat which are clustering to commemorate April’s centenary of the Titanic sinking; and another group, led by Sadie Jones, which uses twentieth-century, often post World War II or colonial periods to explore family alienation, parental attachment and class from a female perspective.

Moving between Kenya and the UK in the 1940s and ’50s, Shaw’s heroine is a figure of post-war constraint, bound by her era, her switch of class and her contained grief for a missing brother and an absent father. But Meg’s modernity and inner landscape, redolent of a wisdom beyond her years and experience, can also defy plausibility.

Disaster descends – or threatens to – repeatedly in A Stone’s Throw, shedding a dense contrasting shadow against the novel’s devoted romanticism. Meg’s love for that missing brother and for the soldier she meets briefly on board ship; and her son Will’s passion for a school friend are the book’s real engines, expressed in Shaw’s discerning, shapely prose.

Like Jones’s The Outcast or Rachel Heath’s The Finest Type of English Womanhood, this is a novel pitched at that reading-group-driven appetite for intelligent heartbreak in a shifting social milieu. Shaw’s particular strength is in her quiet yet intense power of evocation which gives the book’s opening its impact and lights up a handful of other key locations: an African garden; an English beach.

Tasteful and well crafted, this is a story of sensitive souls and well modulated pain. Elemental, however, it is not.