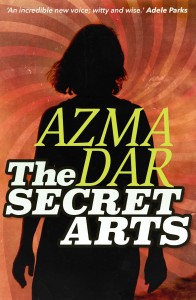

This, our third Dean Street Press extract, features an accomplished and blackly comedic debut novel set in Pakistan. Azma Dar captures the exuberance and dark side of a small community whose traditions are under attack from the forces of greed, jealousy and thwarted revenge.

This, our third Dean Street Press extract, features an accomplished and blackly comedic debut novel set in Pakistan. Azma Dar captures the exuberance and dark side of a small community whose traditions are under attack from the forces of greed, jealousy and thwarted revenge.

To buy The Secret Arts, click on these links: Kindle Kobo Nook iPad Googleplay

*

The Secret Arts by Azma Dar

Chapter One

Colonel Anwar Ahmed Ali sat in the garden, eating French toast and tomato omelette. He pushed the eggs to one side and pulled his dressing gown tighter around him as a chill breeze swept over the lush Murree hills. He wouldn’t have any appetite until after tomorrow. He lifted his tea – for all his military training and precise table manners, at home he drank his tea in a bowl, much to the amusement of his friends. He wiped his grey moustache gently with a napkin and called his housekeeper, a tiny old woman with thick crusty surma in her eyes, and richly dyed black hair.

‘You haven’t touched it, Saabji,’ she said, putting the things into a tray.

‘I can’t, Gago.’

‘Really, Saabji, you must. How otherwise will you ride the white horse?’

‘Don’t be silly, Gago. There will be no horse, no band baaja or other nonsense. I’m not going to make a fool of myself. I know what they are saying in town – I can’t imagine what the poor girl has to listen to.’

Gago looked inside the teapot and poured some into an empty glass for herself. She sat down on the grass.

‘It’s wet,’ said Anwar.

‘My dress is thick, and so is my skin,’ said Gago. ‘Don’t worry about the girl – I mean the future Memsahib. She’s very happy. Looking forward to becoming queen of this palace.’ She gestured hugely with her arms at the mansion behind her, one of the grander residences in the small Pakistani town. Trails of bright pink bougainvillea tumbled over the austere building like the strands of an unwanted wig. Originally a brighter yellow, the walls of the haveli had faded to a chalky vanilla, and the roof was tiled in pale blue. There were colonnades of stone arches on both the first and second floors, creating a verandah on the lower one, and a series of balconies on the upper. To the left of the house was a wide circular tower. Unlike the rest of the building it had a flat roof. The huge column of stone was broken by only two windows, until right at the top, where eight of them went all the way round it, three of them opening up onto another small balcony.

‘Take the egg, too, Gago,’ said Anwar, offering her the plate.

‘No, no, sir, poor stomachs cannot digest wealthy foods,’ she said. Although after forty years in his service she was accustomed to his kindness, she never relaxed totally before him or took what she perceived as liberties. Drinking ordinary tea was one thing, but consuming even the leftovers of the master’s specially cooked meal right in front of him was bordering on insolence. It would be eaten, later, but out of sight, in the kitchen.

‘May God reward you, Saabji, and give you the child you have been yearning for.’

Anwar winced. After it had happened, the thought of remarrying had filled him with horror. It had taken years for the memory of those torturous weeks and the screaming, dreadful final moments to ease their crushing grip on his mind. He wasn’t sure what he was hoping for, perhaps just anything better than that last disaster, and he prayed that his insistence on selecting his own bride this time would go some way in helping prevent such a calamity. Even now, he was happy alone, and personally didn’t care if his name died out with him, but there was his mother, over seventy and counting breaths, yet still croaking orders he couldn’t refuse from her room upstairs.

‘Higher, higher!’ yelled Gago later, to the man attempting to adorn the outside of the mansion with an endless string of fairy lights. ‘The house must be crowned with glory on this joyous day. Come on, only eight hours to go.’

‘Why are you bothering with all this?’ asked Anwar, wandering out into the garden. ‘I’ve told you a thousand times I don’t want a fuss.’

‘Madam’s orders. The town must know the family is celebrating. Do they flash? I told you I want a disco effect.’ Gago waved a fist at the lights man.

Anwar, unable to bear the vision of entering his solemn new union before a backdrop of pulsating neon, disappeared inside the house, only to emerge seconds later from his bedroom window, brandishing a shimmering sherwani jacket.

‘What the hell is this?’

‘Golden suit, saab,’ said Gago, without removing her eyes from the coil of paper bunting she was busy trying to loop over a rose bush.

‘I refuse absolutely to wear this. I’m wearing the black suit I have – English style, and that’s it. Understood?’

‘Saabji, you’ll break Madam’s heart,’ said Gago. She shook the ladder. ‘Eh you, tell saab he should appear in full majesty.’

The lighting expert, who was on his way down, clutched at a step as she wobbled him.

‘She’s right,’ he said. ‘You’ll look like royalty.’ Gago winked at him. ‘And I’ll be up in a minute to apply the Mr Grecian,’ she said.

‘What?’ Anwar was puzzled.

‘You can’t go to your wedding without dyeing your hair.’

Anwar could only splutter.

‘Get ready with a towel on your shoulders,’ instructed Gago. ‘We don’t have to do the moustache, just the head. Grey black combination, like the Indian film stars.’

The Colonel retreated into the room, slamming the window shut.

From her bed by the window, Begum Shezadi heard this exchange between her son and the maid, and cackled quietly, rubbing her gnarled, jewel-encrusted hands together. The tower room was ideally positioned for listening in on conversations taking place in the garden, an activity the Begum enjoyed for recreation and sometimes necessity. It was for these spying facilities that she refused to leave the tower and move to another, more accessible part of the house.

The room was painted in shiny cream gloss and the doors and shutters were made of intricately carved panels of sheesham wood. A gallery of photographs and paintings hung on the wall to the left of the bed, while the wall opposite was covered in mirrors with an array of frames – hammered silver, etched copper, mango wood sculpted into swirls and flowers, mosaics made of jewel like tiles in emerald and scarlet.

Beside the bed were a folded wheelchair, and a marble-topped table, upon which stood a white plastic box containing the Begum’s medicines and insulin injections, a jug of water, and a radio cassette player, currently tuned into BBC World Service.

It was the room that the Begum herself had come to as a young bride, more than half a century ago, a place that had seen the bloom of life and love, but also the rot of death and blackness of hatred. Anwar’s great grandmother had died in this very bed, diseased by the plague, and it was said that one of his ancestors, driven crazy with greed, had murdered his brother here. The Begum believed in ghosts, and sometimes she thought she could hear these bleak spirits murmuring, moaning, laughing and cursing. She occasionally she wished that one of them would appear and enter her own body, arouse it out of its useless state, make it do extraordinary things, evil if necessary, but at least vital and alive. But she knew such things didn’t happen by will alone. There were ways, specific, sacred, studied.

The Begum wouldn’t insist on the gold outfit or the hair dye. It had taken her twenty years to convince him again, and now she had only hours left. She knew just how much Anwar would take. Even a nudge too far could prove fatal at this point because, after an age of despair, it was happening at last.

Saika had always planned on getting married in white instead of the traditional red favoured by brides in India and Pakistan, but when the time came, the lehnga she fell in love with was the colour of the ripest tomatoes. As her cousin and the woman from Murree’s one beauty parlour arranged her hair in a snaky sculpture of spirals and embedded it with rosebuds, Saika looked in the mirror and thought the dress made her look somehow overcooked. Well, she was overcooked, overdone, aged, mouldy, or whatever it was a girl became once she passed the upper marriage age-limit of twenty-seven. At an almost antiquated thirty-one, she had been saved from the grave of spinsterhood by the Colonel’s spectacular eleventh hour proposal.

It was her uncle Munir’s wife Rabia, also a second cousin of the Begum, who’d acted as the go-between and brought the message. The Colonel wanted the honour of making her, Saika, daughter of Ibrahim and Zubeida, his wife. There was no need for the fifty year old ‘boy’ to come along and be questioned about his education, work prospects, lineage, bad habits and general intentions towards her. All this was well known –although a little reclusive, the Colonel had a reputation for being honest and generous, and was respected and admired by many. Saika’s parents were speechless for at least ten minutes. When he finally recovered, after drinking four glasses of water and three spoons of Gaviscon, Saika’s father said to his sister in law, ‘Please repeat, Rabia, and this time speak clearly. I don’t think I understood you properly.’

‘You heard, Ibrahim. Colonel saab will marry Saika,’ said Rabia with an air of exaggerated casualness, popping a pistachio from its shell, throwing it up in the air and catching it with her mouth. ‘The Begum wants a wedding directly, without the hassle of a long engagement. Which day shall I tell them?’

‘How can such a match be made between those aristocrats and us commoners?’ asked Ibrahim. ‘And our girl – well she isn’t the freshest little flower is she?’

‘If you must know the decision was Colonel saab’s own,’ Rabia said.

‘He’s seen her photo?’

‘Well yes, and he’s seen her around town, gallivanting about as this generation does.’

‘Now, Rabia, my girls are never ones for gallivanting unnecessarily, and as far as that goes, you yourself…’

‘Alright, don’t start. The point is that Colonel saab wanted, for some reason, an old girl, and as we know, Saika is one of the oldest around. It seems that her unreasonable obsession with education has paid off.’

When Saika had announced her intention to finish a degree, Rabia had voiced the fiercest opposition in the family. For Ibrahim, who disliked Rabia and loved his daughter, this had been the only encouragement he’d needed to side with Saika.

‘So, tell me,’ said Rabia, removing a plastic straw from a glass bottle of Sprite and dropping it on the floor, so she could drink without obstruction. She turned to Saika’s younger sister, who was buzzing about in excitement. ‘Eh, Nadia, make some tea. When do you want to set the wedding date?’

‘It’s an unbelievably generous offer, but Zubeida and I need to discuss it with Saika first,’ said Ibrahim, surprising even himself. He already knew he would do everything in his power to make Zubeida and Saika see the benefits of accepting, but he would never grovel at Rabia’s feet.

Rabia crashed the Sprite bottle on the table.

‘Are you crazy? Who in their right mind needs to discuss something like this? That’s why she’s still not married – you and that half-wit wife of yours let her get her own way in everything. Who wants an educated old hag?’

‘You mind your tongue, missus – and why she’s not married I’ll tell you! You’re the hag around here, putting black curses on her chances, drying up her good luck!’

‘You dare to say that!’ Rabia grabbed Ibrahim’s wrists and began waving them up and down in fury. Fearful that she would flatten him within seconds, Saika and Zubeida pulled her off and sat her down.

‘Where’s that tea?’ panted Rabia, wiping her face with her dupatta.

‘Nadia, hurry up!’ Saika called to her sister, before speaking to her aunt. ‘You can tell them to come in the second week of next month. They can decide the date themselves.’ After years of rebuffing the dozens of nice young men her parents had paraded before her with the vague reason of them being ‘not right’, her marriage had been decided in a few minutes. Saika had never even bought a handbag without visiting the shop three times and pondering over the various aspects of the purchase for weeks but she had accepted a husband on impulse. She still wasn’t quite sure why she had done it. She’d seen the Colonel a handful of times at social occasions, and although she had never spoken to him, she’d noticed they had both suppressed a smile during an account of a burglary by a mutual relative, which the rest of the audience was finding harrowing. That was all. The rest of her life had been determined by her instincts and a silent and secretly-shared joke.

The cars beeped in unison as they climbed the final steep corner of the road that led up to the house. The marriage had taken place in an orange, purple and green tent pitched in the street outside Saika’s house, its entrance distinguished by a pair of moveable palm trees, and a wooden signboard stencilled with the words ‘MOST WELL COME TO HAPPY MARAGE’. The Imam had performed the nikaah, wandering in and out of the house to ask permission and obtain signatures from the bride and groom separately. Anwar had been in the tent, seated on a red and green wooden throne on a raised platform, his audience of guests in rows on metal chairs, men at the front, women at the back, while Saika had stayed indoors, in the living room with a few selected ladies. Having received positive responses from both parties, the Imam had recited surahs, read a sermon on the obligations of the married couple, extended his congratulations to the families, and sat back to enjoy a plateful of the dried dates, almonds and crystalised sugar that were being distributed to celebrate the happy occasion.

Now a convoy of cars – mostly Datsuns with a couple of white Suzuki vans and the wedding carriage, a black Jeep, all decorated with strips of coloured crepe paper and balloons and packed to at least double their usual capacity – was returning home with the bride.

Alone in the tower, the Begum sat up in bed and smacked the netted window with her walking stick to open it. Gago had gone with them, after much insistence that she would rather stay and serve her mistress than attend an event as trivial as a wedding. Her mistress, however, had ordered it, and it was unspoken between them no one could report back to her about the proceedings with the accuracy and perception that Gago could. She knew that Gago had secretly wallowed in the preparations for the wedding, taking days to select the garlands, donning the gold jewellery so they could see what it looked like ‘on’, smelling roses to shower on the bride like an experienced perfumier, even though she claimed to have lost her sense of smell during an attack of small pox twenty-five years ago. It amused the Begum that she was, for once, allowing Gago to indulge in her passions by attending the grand finale of her labours. The other two servants, Nathoo and his wife Sharmilee, were downstairs in case of emergency.

The Begum craned forward and squinted down at the road, but could see nothing through the darkness brushed thickly with white, nothing of the newness that was stealing up towards her. But she could feel it in the flutter that beat in the pit of her stomach, in the quickening of her own breath when she considered what her son’s marriage would bring. She twisted the stick and hooked it around the shutter, pulling it to. That was the only drawback of being in her little eyrie that overlooked the world: she could keep her eye on everything, but it was bloody cold. The Begum pulled the other shutter but the stick prevented it from closing completely, so she was forced to lean forward and shut it with her hand. Then she lay back and waited for the fools to arrive.

‘Would you like a cup of tea?’ Anwar asked his bride. Saika was sitting in the middle of the bed, her dress spread out around her in a perfect sanguine circle, crawling with flowers and paisley leaves.

‘No thank you,’ she said. ‘But if you’d like some…’

‘I don’t think I should,’ said the Colonel. ‘Won’t be able to sleep – not that I’ll get much sleep tonight anyway. Oh! I didn’t mean… here, how about a plum?’

As she declined the unappealing-looking fruit, bruised and leaking blackish juice, Saika wondered if these offers of sustenance concealed a more sinister meaning. Her fidgety new husband hardly looked like a master of innuendo, but perhaps he’d been advised to lead up to the expected big event of the night with some subtle hints. The proffering of the plum had required him to sit on a chair between the bed and a table holding a fruit bowl, where he still sat now, eating and gazing unhappily at the ceiling. Would a banana be offered next, she thought, that poor subject of the crudest of jibes, accompanied by an attempted casual slide from the chair on to the bed?

‘I’m sorry we haven’t really met before. I would have liked to…’

‘Then why didn’t you?’

‘I… er…,’ he mumbled something incoherently, though Saika thought she caught the word ‘busy’.

‘What would you have said?’ Saika shifted on the bed. She could no longer kneel in the picturesque bridal pose and moved into a rather less dainty cross-legged position.

‘Sorry. I’ve got pins and needles.’ She realised she was talking too much. Her married cousins had advised her to lie down quietly and go along with whatever he suggested. If she wanted to add an extra special touch, she could also pretend she was having fun.

‘No, no, that’s my fault. I’m so sorry. Would you like a cushion?’ He sprang up from the chair and began padding the area around her with pillows, then stopped and put them back. ‘That was silly, trying to prop you up there. Why don’t you take the dress off and then you can rest properly?’ His mouth clammed up immediately and his face flushed a curious burgundy colour. ‘I didn’t mean… I’ll go out if you want,’ he said, sitting down again. He covered his face with his hands.

‘Look, what I want to say is, I know that you’re an educated girl…you don’t really know me,’ he said, after a moment. ‘If you want to wait a few more days, take your time, it’s fine. I mean, I’ll just get changed and go to sleep… in the bathroom. Get changed, that is.’

She let him sit in the misery of his discomfort for a few moments before speaking.

‘I’m not really that modern, you know,’ she said. ‘But at the risk of sounding it, we both know what’s expected so you might as well come here.’

Come here? That was supposed to be his line! When, of course, he chose to deliver it at what he thought was a well judged and appropriate moment, and with a no longer controllable passion. He had never expected her to say it, and in such a teacherish tone. That was her profession, he knew, but he hadn’t thought he would be treated like a schoolboy, especially not in the bedroom. Or maybe… he stopped these unfounded imaginings to look at her, and saw the devil in her eyes and a hand stifling a smile.

Anwar remembered the first and only time it had been demanded of him to become so instantly intimate with a complete stranger. Then there had been poetry, painstakingly practised, and, instead of champagne to share, glasses of buttery green and mauve pistachio slivers swimming in warm sweet milk (decorated with a strand of obligatory green tinsel). But this time, a fear of foolishness had forbidden the spouting of romantic verses, and Gago had been warned in advance that the bride disliked milk. Instead she had filled the mini fridge with bottles of Polly, Coke, and Bubble Up, and left a plate of heat-inducing dates on the table for Anwar, with the intention that their consumption would fire him into action.

As Saika slipped the dupatta off her head, the shadows drew away from her face and he saw she was prettier than he’d imagined. Her tikka, dangling from a tiny pearled string hooked into her hair, had become tangled. He leaned forward to help, his fingers tugging gently, releasing a floral fragrance that he recognised as Rose Herbal Essence Shampoo. Gago, having seen the advert on satellite TV, had bought him a bottle a year ago hoping it would have the same ecstatic effect on him as it did on the actress, and inspire in him a sudden desire to be married. It had a very womanly scent – he’d given it back to Gago.

As the gold tikka fell into his hand, he was again reminded of that clumsy, pleasant night all those years ago. Her white face and eyes the colour of that green northern lake, his chivalrous removal of all the various jewels on her body (an idea stolen, admittedly, from his favourite Indian film). It had made her giggle. Whenever he remembered, whether it was that early passion or the later treachery, it was always the wildness of her laughter that came back to him.

The machine beeped as the Begum dropped a globule of her blood on to it, and seconds later flashed a large black 5. Good. She could eat her breakfast with sugar to spare. Porridge with a bit of honey and toast with strawberry jelly. She yearned for a bowl of Coco Pops, but they were out of the question – sugary chocolate and rice, a lethal combination. She limited herself to one helping a month and special occasions. There were four boxes in her trunk, imported at her request from various foreign relatives. They would even wrap them up, idiotically asking her to guess what could be inside, even though she’d asked for them herself, and as though she was deaf as well as diabetic, and couldn’t hear the rattle of the puffy particles.

Gago brought in the breakfast.

‘Number okay this morning?’ she said, with an unusually joyous smile.

‘Yes it’s fine.’

‘Hot cup of tea for morning blues.’

‘Just shut up and get on with it,’ said the Begum. ‘How does my son look?’

‘Teasing, teasing! I haven’t been in yet. But Saabji is downstairs, waiting for her to come down before eating.’

‘He would. Too polite.’ The Begum took a large bite of the jammy toast. She refused to read anything else into the sentiment.

Saika gazed out of the window and around at the walls of the house, still covered in fairy lights, the criss-crossing wires much more visible in the daylight, a net entrapping the building rather than a glitzy decorative feature. To the right she could see the morose-looking tower jutting out at the corner. It was where she would be meeting her new mother in law shortly. Last night Gago had informed them that the Begum was tired and they would be given an audience in the morning. Anwar had insisted on seeing her, but the Begum, in turn, desired that he devoted this first night to his new wife.

So, it was done – the ordeal of awkwardness and embarassment was over. They’d spent a night of politeness and measured abandon. It could only get easier.

Saika wanted to know more about him – her husband, she should think of him as now. The term seemed to her bizarre. There had been no more than five weeks for her to get used to it. Last month she was contentedly trying to teach resistant schoolchildren how to spell and paint in an impoverished village school, and now here she was, a minor celebrity.

She put on her earrings, scratching at her itchy earlobes.

‘Ready?’ Anwar was at the door, dressed in a khaki coloured shalwar kameez. He was fair for a Pakistani, but his hair was too long. She would ask him to have it cut. She looked at him in the mirror, and began to see how familiarity could breed a sense of beauty.

The Begum was dreaming. She was twenty-three – no, twenty-one, why not? She was wearing a long gharara, pale blue with silver sequins, red poppies in her two long plaits – not a hairstyle that she particularly liked, and why was she wearing colours that didn’t match? She was on a swing, and a man, standing behind her, was pushing her higher and higher, his hands firm on her hips, strong arms ready to catch her in the unlikely event that she fell. She considered letting go, just for the sensation of being cradled by those muscular biceps, but it was outweighed by the painful possibility of accidently missing and landing elsewhere. But who was he? If she turned her face she could get a partial glimpse of him. In that flicker he looked like the ex-President, Musharraf. Smart though the General was, especially in uniform, she hoped it wasn’t him. He was in the wrong era, anyway. In the dream, her mysterious playmate could be anyone. She could have taken her pick in those days. Now of course, the choice would be more limited, but who knew…? She bit her lip. It was best not to get too excited.

‘Bhoot bangla, you are thinking, no?’ said Gago, scurrying along the dark corridor that loomed long before them, carrying an oil lantern. There were fours doors on each side, seven of them shut, closing around them like a tunnel.

‘But don’t worry, it’s not haunted. I can vouch for that. I sometimes come and sleep up here, if I’m bored. Never saw anything unusual – no witches, killer children’s dollies, men with electrical tools or burnt faces and long nails.’

Saika looked at Anwar, who shrugged, and said, ‘They watch films on YouTube.’

‘Once I heard scratching, but it turned out to be a bat,’ said Gago. ‘You notice no bijli wiring in this bit of the building. Of course Madam’s room is fully fitted.’

‘No one uses this part of the house – we’ve never had it modernized,’ said Anwar. ‘I’ve told Amma to move to the main house but she likes it up there. You know how old people are with their whims.’

‘It seems a shame,’ said Saika. ‘It’s a lovely building.’

‘When there are lots of children to fill it there will be no excuse to keep it closed,’ said Gago, beginning the ascent up the spiral staircase. ‘We had lots of plans for it last time. Saabji and his lady were going to redecorate everything. In fact, Memsahib spent that tragic morning looking at flocked wallpaper and Chinese rugs.’

‘Alright, Gago, she’s not interested in old history,’ said Anwar testily. ‘Once you’ve settled in, you can do what you like with the place.’

Saika was moved by the words, offered so naturally. Last night he’d given her a set of twelve gold bangles, intricately patterned and inlaid with stones. They were pretty, very tasteful. He said they were chosen for him by one of his female cousins. They didn’t trust him in the ladies’ department. But since then, his quiet, unobtrusive attentions to her, and now this, the assumption, without any hesitation, that everything was immediately hers, a shared life, warmed her heart more.

For now, she answered with a smile, because Gago was there, and she had no breath to say much more.

The Begum appeared to be sleeping to Vivaldi. As they entered, she opened her eyes, and turned off the CD with a remote control.

‘Salaam Ami,’ said the Colonel. He gestured Saika towards the bed. Although she’d heard much about the Begum, Saika had never seen her in person. It was believed she had not left her room for the last five years. Now she thought the Begum had one of those faces where the skull beneath was almost perceptible, taut flesh threatening to melt away to reveal only bone. She had high cheekbones, the skin stretched over them tightly, slight hollows beneath the eyes. She must have beautiful once, and even now would have looked graceful had it not been for the inky blackness of her hair. Its incongruity with her pinched mouth and baggy neck, the places where her age was most apparent, gave her an almost comical look, although as Saika took in the heat of her eyes, she realised only a fool would dare to make this woman the butt of a joke.

Unsure whether to kiss the old lady or simply lean forward and have her head patted, Saika hovered somewhere in between, half bent over awkwardly. The Begum touched her on the head and told her to sit.

‘So. You are comfortable here? Everything to your liking?’ asked the Begum.

‘Thank you, it’s all very nice,’ said Saika.

‘Well that’s good. I trust Gago prepared everything for you as I instructed her to.’

‘Of course, Raani Sahiba. Everything first class for the honeymooners,’ said Gago, who was sitting on the floor in the corner with her eyes shut.

‘There’s no need to call me that in front of Saajida. She is one of us now. No need for formality.’

Gago opened her eyes.

‘Shall I tell her or will you?’ she said, looking at Saika.

‘Her name is Saika, Ami,’ said Anwar.

‘Yes of course. Gago, get me some water.’

‘I can get it,’ said Saika, rising and thankful for something to do.

‘Sit,’ said the Begum, her voice quiet but its tone not needing volume for effect.

Gago was already getting the water out of the fridge.

‘You are not here to do the servants’ work. It gives them ideas.’

‘I think Saika was just trying to help,’ said Anwar. ‘She’s used to doing things for herself.’

‘Well, she’ll have to forget what she’s used to.’ Gago passed her the water, and she drank half of it before handing it back. ‘Put milk in it. A good remedy for heartburn,’ she told Saika. ‘That’s a pleasant colour you’re wearing.’

‘My aunt’s choice.’

‘A little bright for your earthy complexion though. Now, about the house. Obviously you’re in charge. I, useless thing that I am, can’t do much, as you can see. I won’t interfere with your methods as long as there’s not a decline in our high standards.’

‘I’ll do my best to not give you any reason for complaint,’ said Saika.

‘We have a routine about the place, breakfast before nine. Lunch at midday. I don’t expect any changes there. You can select menus daily with the cook. There’s no need for you to worry about any of the housekeeping – Gago has been managing everything quite well. When we see she’s no longer fit we’ll think of an alternative.’

Gago, who had gone back into her corner and was again sitting with her eyes shut, said, ‘Gago is full of beans yet, madam. And certainly not diabetic.’

‘Shut up. One day you’ll go too far,’ said the Begum. She looked at Saika. ‘Before you leave, I just want to impress upon you the importance of being… productive.’

Saika thought about nodding meekly but couldn’t help herself.

‘Oh yes,’ she said. ‘The views are stunning. It’s an artist’s paradise.’

The Begum frowned, but then considered, and smiled.

‘They told me you were a smart girl,’ she said. ‘You’re cheeky too, eh?’

‘What are you getting worried about?’ the Begum asked Anwar, who was looking a little nervous. ‘It’s just mother and daughter having a giggle.’ She lifted her stick and pointed it towards the window. Seeing that she intended to open it, Anwar went forward to help, but she held him off with the cane and pushed it open herself.

‘Painting pretty pictures wasn’t the sort of production I had in mind,’ she said. ‘But you’re right. The views are stunning. They almost make me wish I was young again.’