In an exciting departure from the norm, bookoxygen is spending the coming week showcasing writing from a new independent publisher, Dean Street Press. This digital publisher ‘devoted to producing, uncovering, and revitalizing good books’ is building a list that includes literary, crime and cult fiction as well as non-fiction on subjects including music, entertainment, history, biography, memoir, art and sport.

In an exciting departure from the norm, bookoxygen is spending the coming week showcasing writing from a new independent publisher, Dean Street Press. This digital publisher ‘devoted to producing, uncovering, and revitalizing good books’ is building a list that includes literary, crime and cult fiction as well as non-fiction on subjects including music, entertainment, history, biography, memoir, art and sport.

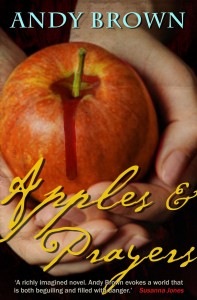

Over the coming days we will be offering extracts from three Dean Street novels, starting with the debut novel from established poet Andy Brown, Director of Creative Writing at the University of Exeter.

To buy Apples and Prayers, click on the following links: Kindle Kobo Nook iPad Googleplay

*

Apples and Prayers by Andy Brown

I

My name is Morgan Sweet.

Sweet was the name the village gave my father. Richard Sweet of Buckland. He lived a year or so longer than my mother – may God’s Love enfold her, His Light shine upon her – although in the short time he alone cared for me, I came to know him little.

They say his fields produced the most abundant, sweet hay in our parish, year on year without fail and so they named him after the produce of his land. Those fields of my childhood were golden and florid, like the Land of Cockaigne, where a child could disappear and while away her hours in reverie.

My mother took her name from her own mother and she from her mother before her: Gillian, or Gilli for short. She was the prettiest flower that ever grew round here. That’s at least as I remember her, for all the little time we had together on this earth. She was born in the quiet settlement of Buckland, where I myself was born and where I’ve lived this whole, fleeting life.

I was born some twenty-something years ago, when King Henry was still young, commanding his throne with fairness and wisdom. I hardly remember my early years, save for the presence of three brothers and two sisters, all of whom preceded me and looked after me, youngest as I was in our country home.

My infancy and childhood flown by, our family number gradually became fewer. Both my sisters died untimely deaths, God protect their immortal souls. First went Caroline – so proud and haughty, we used to mock and call her ‘Queen’, carried off by the plague these many years past. Hers was a dreadful death and it tore our hearts to see it. The boils and eruptions turned her flesh from soft and girlish blushes to the puckered skin like that around a rotten fruit. Then there was Victoria, who turned crimson with the fever and terrified us all exceedingly, she looked so fearful in her quaking agues. Victoria too is gone.

My brothers left the village shortly after my sisters died and left me here alone with our father, to keep the hearth and save the family name. My older brothers, Wat and Ellis, had taken off to new estates, wandering to Whimple and Payhembury, beyond Exeter. There they laboured until they could afford a tenancy of their own. They also took wives for themselves. Wat’s woman was an Endsleigh, whose family was famed in the wool trade. Ellis’s wife was a Moore, whose father was scribe to the Justice. I seldom saw them after they were married.

My third brother, Pip, jumped upon a wool cart heading north and rode away to a new life aboard the trading ships. No doubt he made something of himself, one of those sailors who brings back the spices with which I baked my Lady’s sweets and ginger breads, though once he went off on the wool cart that was the last I ever saw of him. With no Pip left to hold our family together, I was left alone in Buckland.

My father was a villein of moderate means, tenanted here to farmland on Lord Ponsford’s estate. We were never the poorest of families – my father earned a good, steady income from the arable he farmed – but neither were we wealthy. Sometimes he could be a kind man, letting me play on the church green, or in his hayfields with the other children from the neighbours’ homes when, in truth, we should have been helping to bring in the animals, or harvest the season’s crops. But then again he could often be stern, with the quickest of tempers and would frequently swill down more than his fill of ale or cider.

When he was in his cups, he used to fight with my mother. Then he treated her roughly, in wicked, hurtful ways; she who always worked attentively to keep her children clothed and safe and fed. If it hadn’t been for her, each and every one of us would have quit this world much sooner, uncared for and neglected, like famished stock in a run-down barn. The name my father went by was Sweet, but in truth he was a bittersweet man and everybody knew it, even he.

My father had survived the smallpox in his youth and his face remained pitted and red until the day he passed on. So profuse were the marks on his face, that the young ones of the village used to taunt him in childish ways and called him Spotted Dick, a name he bore well, most of the time.

But it was for bearing of another kind that he was famed round here. Once, he rescued a pair of stranded heifers from the burst banks of the river, the cows in dismal jeopardy of drowning. He put his life at risk to carry them back across the torrent to safer pastures on his own. So, when he wasn’t Spotted Dick, the children whispered Stockbearer, although they used these names with caution and only when he might be out of hearing. They knew full well that he could, if he wished, crack the skull of anyone offending him, he was that broad and full of muscle. But he wasn’t only thick in the bones, he was thick skinned too and, mostly, bore whatever jeering came his way.

My mother had an altogether different nature and was thin-skinned as a berry, a constitution my father often abused. When she first married him she was, by all accounts, meek in her ways, but soon learned to bear the brunt of her husband’s eruptions. She was a Bowden before she married and that family still holds sway round here for their stubborn ways and resolution. I know little more of her past than that.

Having borne him six children, our mother drowned in the river one day in winter. She must have slipped down a treacherous bank that the herdsmen’s sheep had muddied. She banged her head on one of the broad flat stones the village women use for beating clothes on washday.

She went underneath the waters in a swirling pool.

Death bides his time and, of a sudden, claims us. Most never know when.

My father wasn’t there to do any rescuing that morning. Cattle he could rescue. Women he could not.

Later that afternoon, when she failed to return home, a search was organized to scour the fields for mother. The whole village came out to look for her, turning over every stone and sifting the bushes by torchlight, well into the night. Their efforts turned up nothing.

The next day the miller, Billy White, found her body washed up on his water wheel along the leat by the outskirts of the village.

In life, my mother was a tall, fair woman, with a thin face that carried the attractive red blush of a pippin. In death she was bloated, her cheeks all washed out, so we hardly recognized her as they pulled her into the village on the bier.

Coppin, the carpenter, fashioned her a coffin out of floorboards, a box my father paid for with a sack of grain and fist of coins. It was a wretched, though maybe merciful end to an arduous union, a marriage she had borne without complaint, God rest her soul.

When my father himself died, not so many months after his wife’s body was pulled from the waters and turned to the earth, I came to the service of my Lord and Lady Ponsford at Buckland Barton. Perhaps my Lord and Lady took me in because of some sense of responsibility, some recompense that my mother’s body was caught beneath the water wheel of my Lord’s miller, although he could hardly have been blamed for her misfortune.

However it was that my contract at the Barton came about, it’s been as stable a home as any I could wish for. I’ve happily worked my way through the ranks of service for the past twenty years. Everything I’ve learned has come through them and I’ve tried, myself, to pass that learning on to Alford, my help and serving girl. I can bear few grudges or grumbles; this life has, by the Virgin’s grace, been mostly free from conflict and misfortune.

It really all began in June, quite fresh still in my memory, although the sad events had been building all year, like layers of stone in an old barn wall. Come June the meadow grasses were growing up good and strong through that stonework themselves: sweet vernal, fox-tail, brome and rye, wild oat, cocksfoot, timothy. Their tall heads swayed through summer days in the undulant breezes that combed the fields and meadows, waiting for their later reaping in the month’s haymaking. To the back of the Barton, roses climbed the house’s wall in lush display, while others stood singly with perfumed pride in the parterre beds of my Lad.y’s garden. The beginnings of fat berries were forming on the fruit bushes already. Peas and beans were plenty for our pot. At the edge of the spinney we gathered in summer mushrooms for stewing – morels, chicken of the woods, summer truffles – copious and earthy, firmly-fleshed. In my Lord’s woodlands, the leaves on the oaks were opening, signaling the sovereign rule of summer. In their branches, the fledgling birds had flown their nests. Above in the clear blue air, swifts danced their madrigals. At twilight moths flew in the oak woods, chased by hungry bats, eager for their meal of evening bugs. On a still night you could hear the faint trace of their voices as they hunted on agile wings between the trees, their clicks and chirrups like the whirr of the ratchet turning on my spinning wheel. By sunset, the yard was filled with froglets moving from puddle to garden pond. I went to my truck each night in two minds: delighting in the growth and glut of summer, yet troubled by what might come with this green explosion.

The trouble was accountable enough.

Within days of the calendar turning, some news was brought to my Lord at the Barton – a gentleman of substantial means appeared with his servant at the manor. It wasn’t often that my Lord was given to receiving men of such high standing as this, although he and my Lady entertained knights and other squires from time to time within their home.

The visitor that day was a well-set man with sturdy hands to grip his mount’s reigns and legs like trunks, which bulged in his garters as he dismounted from his mare, one of the expensive and well-known greys from Bickington stables. She had a broad brow and muzzle and wore a long bit between her teeth to give him firm control. I took her reigns and tethered her to the post above the water trough. Her neck and withers were white with heated sweat. He must have pushed her hard along the lanes.

When she was drinking healthily from the butt, the gentleman brushed past me into the house and I took a moment to admire his plush attire: a velvet doublet with star-shaped slashings, after the European fashion; a jornet round his shoulders and a peaked cap, like one of those exotic pineapples traded from the spice merchants’ ships. Perhaps my brother Pip’s. He was the most magnificent bird in the roost and his serving man was equally attired in the finest livery. He gave me the look as they entered the hall and I turned to dodge his gaze and loosen the tackle on their animals. Something worth of note was now afoot.

My Lord met in private with the gentleman and his equerry, in the curtained chamber set off from the Barton’s great hall. They stayed there in discussion all afternoon until Alford and I were bound to serve them supper in the evening. Then they descended the stone stairs from the garret and arranged themselves around the long elm table. I couldn’t help but overhear their discourse. It seemed to me my Lord’s face was truly grave.

‘…which confirms that war is on the point of breaking out with France,’ the gentleman was saying, gulping down a mouthful of wine and wiping at his whiskers with a napkin. It seemed to be going down agreeably enough with him, although the news they were discussing wasn’t so well received by my Lord.

‘And with Scotland also?’ he replied.

‘Indeed,’ the guest said. ‘And all of this with Cornwall on the march into Devon.’

‘The Cornish have been restless the whole year, ’ my Lord said.

‘Word comes they’re near upon Crediton,’ said the visitor, ‘and some armed detail broken off to Plymouth. Even now they’re at Plymouth Cross.’

He appeared well-informed about rumblings among the common people and uprisings around the country and I wondered if he was captain of some band of radicals. There was, we knew, unrest from east to west.

‘Further abroad,’ he went on, ‘disturbances in the home counties. Spreading through Oxfordshire. Somerset. Wiltshire. Over towards Wellington. The whole, determined country!’

‘And there,’ my Lord paused, ‘we have the proof of this new tax on sheep and the increase in prices on cloth.’

The visitor held his gaze and the two men nodded in agreement. His serving man gave me another sidelong glance that lingered too long, a look I shrugged off as I cleared their dishes. I leaned across the equerry, who had to slide along the bench to give me room, pouring wine to satisfy the thirst of my Lord and his visitor. The equerry I gave none.

‘It doesn’t go down well with the commons…’ the visitor said.

‘It doesn’t go down well with me, Sir!’ said my Lord.

Now, my Lord was a law-abiding nobleman and loyal to the King, it needs no saying. But this talk of risings in the Cornish lands far west of here, their following march into Devon and my Lord’s annoyance at the taxes and the rising price of cloth, all this made me think he might, just might, desire to befriend the rebels’ cause.

Trouble had walked through our door.

My own man, John Toucher, was right; it would serve our county poorly if such tithes and taxes mounted any further. No wonder then that restlessness had stirred our people’s hearts.

June is the season of feasts and carnivals and, with little labour underway in the fields, we celebrated our Saints’ days. We reveled. The harvest comes later and with it the busiest time of the year – the corn sheaves will be gathered in and stored in the threshing barn over the winter. But with the harvest some time ahead, all things need to be ready and in their proper place. June is the month to make such preparations and the men of our village were filling their time with these tasks. Johnny Voun, the cooper and wheelwright, repaired the wheels on the wagons and handcarts, mending their struts and iron rims, while Dufflin and Coleman fashioned tools and fittings in their busy forge. The carpenters were also well employed. Coppin and Woodbine mended boards for the floors of the carts, so none of the harvest would spill to the ground, while the humble task of greasing pins and axles was given to the simple Sidney Strake, who managed this chore throughout the day, at ease, without becoming bothersome and getting in the way of working men.

Around the fields, other small jobs could be attended to at this time, like pruning back unruly shrubs and bushes. The sun and the drought finishes them off, driving back unwanted scrub. Children were also clearing briars and bracken and scooping ditches to drain the waterlogged corners of fields, spreading the mud from the trenches for next year’s richer pasture. Such tasks are vital and filled our days of waiting when the crops were ripening.

It was while all these tasks were ongoing, that incidents and accidents gathered up our community.

Across the lanes and meadows in the parish of Sampford Courtenay, where sometimes we went to hear the Sunday Mass, Whit Sunday was observed by bubbling crowds beneath the tower of St. Andrew’s.

There the village priest, father Harper, dutifully said the new English service of the Mass, as priests across the country were commanded by King’s Council. The reverend father stood there in his new, plain robes; such dullness that held nothing of the customary colours, all bleached and white as the hairs on the old man’s head. He also gave his reading from the Book; this new tome of Prayers that Royal instruction had decreed. And, as he was bidden by these new laws, he also spoke the service in the vulgar tongue, in place of the sacred Latin that we’ve always venerated.

Other than these perversions to our faith and the mutterings and protests that came with them, the gossip was that everything went by that certain day without event, ignominy, or strife.

The following day being Whit Monday, a troupe of us from Buckland set out early on ponies and carts to go to the Sampford fair. It was, again, a Holy Day and set to begin with Mass in Church, before the village fair upon the green.

The congregation was larger even than the day before. The crowd stretched back, out of the village and into the country lanes. There they stood beneath the protection of the boundary’s granite crosses, set in place to ward away the Devil, where weary rovers stopped to say their prayers.

By mid-morning we were ready to make our way into the church, following the lead of father Harper along the path to life eternal. Harper was an old, distinguished priest, nearing four-score years in age, long in the beard and wrinkled greatly across his brow, like the shell of a seasoned nut. And yet, although now old, he still seemed every bit as robust as when he’d been half his age.

We followed on his heels along the path to church, the way a flock is led to lusher fields by the shepherd.

It was then he was stopped in his tracks. Two eager kinsmen.

The first of them spoke and set an awkward question. ‘Will you speak the Mass today, father, as we’ve always had it, or are we going to get that English stuff you gave us yesterday?’

It was surely the thought on everyone’s minds, though none so far had dared to voice it. From my place in the ranks, I heard father Harper’s reply.

‘In obedience to the law,’ he said regretfully, ‘in English, sons.’

The two men – Underhill the tailor and the yeoman Segar – looked to each other and nodded. The first who’d spoken, Segar, then continued.

‘King Edward’s been enthroned for three years now,’ he said. ‘Just three. And already in that time, against the wishes of his dying father, he’s made these changes before he’s come of age. What does a boy know of our ancient customs?’

His voice and his concerns commanded our attention from the first.

‘What is this ‘Book of Common Prayer’, anyway?’ he asked us, turning from the priest to face his audience. The way he said its name made it seem nothing more than a collection of nursery rhymes, nothing like our blessed breviaries, missals, psalters.

‘We’ll stand by our religion, as appointed by King Henry,’ said Underhill, joining him. ‘Speak the Mass in Latin, today and hereafter, with all the ceremonial as normal.’

We waited nervously upon the priest’s reply. When it came it was carefully measured.

‘Your words are steered by passion, sons and, were I yet a freer man, I’d warm to their commitment. But I am poor already and, if I don’t present English prayers today then, no doubt, I’ll find myself fined my yield and poorer for it tomorrow.’

The priest then bade them move aside, with unrushed gestures.

Underhill, however, wasn’t to be moved and stepped across the priest’s path.

The old man looked him down, but the dissenter continued. ‘Isn’t your faith worth more than your wage, father Harper?’

‘It may well be, master Underhill,’ he said. ‘But it isn’t worth imprisonment for life. Nor loss of all I own. You also might take heed of the Law, my fellows. Those found persuading priests to break the Law will also lose possessions, or be jailed.’

Segar and Underhill looked at each other, an eyebrow raised in hesitation here, a hairline scratched in perplexity there.

But the assembled were now behind the two men’s boldness and, perhaps sensing a greater discord in the air, the priest resigned himself to meet their will, despite his better private judgment.

He retired for some moments to his vestry, to dress himself in his usual Catholic cope. We stood and talked together about occurrences. He soon reappeared, greeted with cheers and hollers of relief.

Things were once again as they should be.

We followed him into the church, where we heard our Latin prayers and Mass, In nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti, Gloria Patri, et Filio, et Spiritui Sancto… divine, delightful words we valued highly.

Afterwards we poured back out, exultant and excited onto the green. When the few stray sheep had been cleared, who’d wandered here through some tenant’s broken fences, there followed much by way of entertainment, games and amusements, with Church Ale ladled out by wardens at the Church House and, with it all, a share of spirited debate on matters of faith and Holy rites.

‘That other Mass would have us believe the Sacrament’s no different from any other flaming common bread,’ said Segar.

‘And why should our children be only baptized Sundays? What’s wrong with their birth day as usual?’

The people were stirred into shouting out their grievances at random: Our Holy shrines and rood screens ruined… images of Christ and Mary turned to flames like heretics themselves… I’ll still use my beads, despite whatever ban… I’ll still recite the Rosary for succour… and as the mood intensified, Underhill pulled himself up onto a platform of boards on the back of a cart and commanded the crowd from this makeshift dais.

‘Listen to me,’ he urged us. ‘We’re all, without exception are we not, good Catholics in this shire?’

We cheered and gave him our assent.

‘So what in Hell’s this English Book foisted here upon us? Isn’t Our Lord any longer present in the eucharist? Isn’t the body and blood of Christ present truly in the bread and wine?’

We quieted at his thoughts and, in that hush, the speaker rallied.

‘The sacrament’s a sacrifice to God, of Jesus Christ, who’s present in that bread, that wine. This book would have us believe these changes of bread to flesh, of wine to blood, don’t ever take place! They’ll not even let us take wafers, but rather say you’ll receive everyday bread!’

Another cheer rose. Now that he said it like that, these changes were a sham of our convictions.

‘This English Mass is an insult to our faith. Our prayers before communion, our matins and our evensong, these things are nothing when spoken in English. Yes, we love our country’s tongue, but sacraments were made to hear in Latin and in Latin we will hear them!’

‘Oh, right, Mister Underhill,’ a voice called from the back. ‘And what do they mean, exactly, these Latin words, pray tell me if you wouldn’t mind? I’ve never understood them myself…’

The laughter moved among us like a wind through stooks of corn. Moments later we settled.

‘In truth I don’t know the meaning of all the words,’ Underhill replied, ‘but I do know they’re the language of the soul divine and, being so, I couldn’t hope to grasp their every meaning.’

His answer was considered. We applauded.

‘I also know these Holy words are safeguards of our faith,’ said Segar. ‘Take them away and you take away the very grounds on which our lives are built!’ With this, he too clambered up onto the pedestal and joined his partner there above our heads.

‘They don’t even say that marriage is sacred,’ he said.

Beside me stood our village newly-weds, sweet Alford from my Master’s house and Dufflin the blacksmith’s boy. They held each other’s fingers loosely amongst the close-packed crowd.

‘Such ceremonies see us through from crib to coffin,’ he continued. ‘They mark the passing of our lives and give us our Holy Days. Days like today. Days when we can take a hard-earned rest…’

With sentiments like these, they couldn’t fail to win their fellows’ trust. Yet the rest of their speech came at us like a torrent. I wasn’t sure if we were hearing the balanced flow of reasoned thought, or the sound and passion of some waterfall come crashing down around us, meaninglessly on the rocks. There was so much noise by now that all I heard was fragments bashing round like boulders clacking in a torrid stream… no candles at Candlemas,… no ashes on Wednesday… no palms on Sunday… rob you of your hallowed rights as soon as rob your land… the whole thing made me feel unwell and giddy. For steadiness, I filled my mind with thoughts of our Holy Mother and of my own mother.

It was Segar who then rounded his attack on the King’s Law. ‘I tell you now, we will have all such laws as made by the late King and none other. Not til that boy King comes of age!’

The crowd then burst forward and carted their spokesmen around the green, high on their shoulders. Afterwards, the talk burned on and smouldered like the very oil of baptism itself, which these apparent laws would see abolished.