A Conversation with Karen Jay Fowler

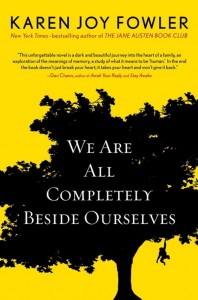

Barbara Kingsolver, reviewing Karen Jay Fowler’s latest work of fiction, We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, in the New York Times, described it as ‘a novel so readably juicy and surreptitiously smart, it deserves all the attention it can get.’ Now the book is getting heaps of additional attention as a result of being shortlisted for the 2014 Man Booker Prize.

Barbara Kingsolver, reviewing Karen Jay Fowler’s latest work of fiction, We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, in the New York Times, described it as ‘a novel so readably juicy and surreptitiously smart, it deserves all the attention it can get.’ Now the book is getting heaps of additional attention as a result of being shortlisted for the 2014 Man Booker Prize.

Elsbeth Lindner interviewed Karen Jay Fowler in New York in 2005, during the author’s publicity tour for The Jane Austen Book Club. That conversation touched on many topics relevant to the writer’s background and motivations, and offered a tantalizing glimpse of work to come. Here it is.

*

For a person who, in the course of our conversation, told me repeatedly how lazy she is, Karen Joy Fowler is not exactly sitting back and watching the daisies grow. I caught her between trips to New York, New Orleans, Santa Barbara and Florida, all within the space of a single week. The Jane Austen Book Club has been precisely the kind of breakthrough book that writers fantasize about, and Karen Joy Fowler has not responded lazily to the changes it has brought about. When the novel became an international bestseller last year and the invitations and opportunities began flooding across her desk, ‘I realized this might never happen again, so I said yes to all of them,’ she confessed, with a laugh.

There speaks the disarming voice of a writer still a little stunned at the turn in her fortunes. Fowler’s voice is indeed a remarkably frank one, soft and occasionally weary – which is hardly surprising – as well as ironic and at times halting, for example when discussing moments of significance.

One of these came at the age of 13 or so, in the early 1960s, when the civil rights movement was in full swing. The young Karen found herself very caught up in the horror of the images seen nightly on television – ‘guns, dogs, hoses being turned on peaceful demonstrators’. Not only did the violence awaken her political consciousness, but it also marked her ‘as a narrative’. Although the urge to write had been with her at a much earlier age, it had disappeared in her teens. Now, suddenly and violently, a painful story of ‘good people and bad people’ had been clearly delineated and she would not forget it.

Later, at college, another wave of politics struck her – feminism. She began to notice and read more women writers, such as Doris Lessing. ‘I read The Golden Notebook and wondered: “Why do the women in this book make sense to me ?” They were feeling and thinking things I thought and felt.’ Female protagonists became important to her, and would do so again, once she became a writer.

That career was set in motion during a crisis that developed around Fowler’s thirtieth birthday. Having studied political science, focusing especially on Asia, then spending some years raising her two children, Fowler felt the time had come to do some stock-taking. ‘I saw a lifetime in which I’d flitted from thing to thing and therefore was competent at absolutely nothing.’ She was also growing more conscious of slowing down physically at her evening ballet class, where groups of sixteen-year-olds were passing through and she was standing still.

By chance, the Davis Arts Center in California was offering a creative writing class as an alternative to the ballet session, at exactly the same time. Fowler was able to swap without needing to renegotiate her free time with her husband. And this is where the famed laziness made one of its appearances. Fowler believes that up to this point her fear of failure had inhibited her from working hard or seriously committing to any one thing. So the writing course became ‘the most serious commitment of my life. This was what I would give my heart to, succeed or fail.’

Where, I wondered, had that fear of failure come from, if she had enjoyed, as I had read, ‘a distressingly ordinary life’? In fact, her carefree childhood in Bloomington, Indiana had been disrupted in 1961 when the family moved to Palo Alto, California. ‘I had been a very popular, easily successful, outgoing child and Bloomington was a very small pond. At eleven in Indiana, I was a tomboy, a young girl. But to be eleven in Palo Alto was to be a young lady.’ Suddenly, Fowler was no longer playing jacks and climbing trees. Instead, she was expected to ‘put my hair up and have a crush on somebody.’ It was a difficult transition and one that marked her. In choosing to tackle creative writing, ‘the first thing I did was contemplate future failure. It liberated me to the extent that I put in enormous effort for the first time.’ She paused. ‘It didn’t make the inevitable failures any easier.’ Another easy laugh.

Until full-blown success arrived last year, Karen Joy Fowler certainly weathered her share of literary failure, but also built a solid reputation for herself as an unusual, thoughtful and inventive writer. It took her two and a half years of constant rejection to sell her first novel, Sarah Canary, published in 1991. This was an experience she found both bewildering and instructional. Some twenty-five rejection letters and at least one change of agent left her wondering what to make of the book’s excellent reviews, prize nominations and citation as one of the New York Times’s notable books of the year. ‘If the book was so good, why had no one bought it ? And if it was not so good, why say it was ?’

Readers familiar with Fowler’s writing will hear something characteristic in that question. For Fowler is a writer interested in the contrariness and contradictions of the world, in the juxtaposition of differing points of view, and the ironies ensuing. Her academic studies were devoted to the meetings of cultures, and attempts to talk across political divides. Sarah Canary, about a Chinese railroad worker in late-nineteenth-century Washington State, was a book she hoped would bridge the gap between mainstream and science fiction. Her next novel, The Sweetheart Season, published in 1996, she regards as ‘a romantic comedy with historical and fantastical elements’. And her third novel, Sister Noon, published in 2001, explores a mysterious historical figure, Mary Ellen Pleasant, a black woman who for a time passed for white.

Fowler has described herself as much more attracted to writing historical fiction than contemporary: ‘When I think about contemporary settings I feel my energy flag.’ Where, then, does The Jane Austen Book Club fit into the arc of her writing ? The idea came to her while she was mooching in a bookshop, waiting for a friend’s reading to begin. She saw a sign for ‘The Jane Austen Book Club’ and thought it was a novel, one she would – as a life-long Austen fan – love to read. When she discovered it was an advertisement for a book group she was disappointed, but also simultaneously struck by the thought that here was a book she was born to write.

Its simple structure – six novels, six characters, six chapters – fell easily into place. Best of all, Fowler knew Austen’s novels inside out. She had read them at different times of her life – at thirteen, as a student, as a mother with young children. ‘They were a touchstone for me. The books became a kind of conversation both with the writer and with who you were when you read them.’ In a way, the women in her fictional Jane Austen Book Club are all versions of Fowler herself, although they have different histories to hers.

That the book broke her mould – no research, no historical setting – also seemed fortuitous. The fact was that sales of her work had been dropping, novel by novel. Fowler knew her idea was a commercial one, because of Austen’s popularity, but it did not occur to her that the book group connection would give it such a massive boost. She feared that writing about a figure as popular as Austen would leave her exposed. ‘I love Austen and I get snippy when people start mucking about with her.’ She told herself she was not writing a sequel, but a novel about people reading Austen. This, she admits, is not a distinction everyone has been happy to make.

Clearly, accusations in the British press that she wrote the book to cash in on the phenomenon of reading groups are untrue but also not wholly unexpected. When she was writing less commercial books, Fowler points out, no one accused her of being commercial-minded, nor would they while she remained unsuccessful. With success comes that snippiness, at least in the UK. In America, the response from reviewers has been rather more enthusiastic, with the New York Times raving: ‘This exquisite novel is bigger and more ambitious than it appears. It’s that rare book that reminds us what reading is all about.’ And the writer Thomas Disch has declared it a ‘metafiction’, ‘an intricate postmodern cotillon’. Fowler is more than happy to agree with that comment.

Meanwhile, fulfilling all the obligations of sudden stardom has left her little time for writing, although she was happy to touch on not only the next book she wants to write, but the one after that as well. First comes ‘a kind of murder mystery, contemporary, set in Santa Cruz, which is a wonderful setting in California, with a university and redwood forests and oceans and beaches and left-wing politics and drugs and sexual variety and a hippie ethos.’ After that she will turn to the novel she has already started, concerning the 1950’s movement devoted to raising chimpanzees in home environments in order to explore the extent of their language skills. I wondered why, if she had started it, this novel would be coming second. Fowler answered that she cared too much about it to make it the next book; she wanted to take her time.

Perhaps this was a glimpse of the writer who insists she is lazy, who doesn’t spend all her free hours at her computer, but likes to take walks and do crossword puzzles. Yet I found it hard to detect a work-shy writer in Fowler’s passion for research and restless intellectual curiosity. If this is indolence, it has its productive dimension, which is just the kind of contradictory conjunction that Karen Joy Fowler enjoys.

We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves is published by Serpent’s Tail in the UK and Putnam in the US.