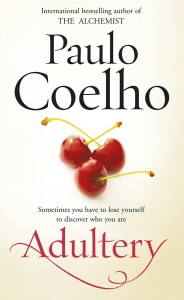

Published by Hutchinson UK, Knopf US

Published by Hutchinson UK, Knopf US

304pp/272pp

Reviewed by Alison Coles

Paulo Coelho’s huge fan base, earned from The Alchemist (which alone has sold 65 million copies) and his fourteen other titles which together have sold some 150 million copies worldwide, will no doubt be happily anticipating the publication of his new novel Adultery. And the good news for them is that, as with The Alchemist, the book is a simple and soulful parable. At a time when so many things appear complicated and insoluble, part of Coelho’s appeal must lie in the simplicity of his message. Adultery tells a story which demonstrates Coelho’s take on a metaphysical ‘truth’: in order to return to your present place, psychologically stronger and in a better soul state, you have to embark on a journey with no guarantees of a good outcome.

Coelho has certainly battled his way to bestsellerdom. Born in Brazil in 1947, he always wanted to be a writer. His parents, however, thought he was anti-social and psychotic and had him put into a mental asylum three times. On his release, he became a hippie and then a best-selling lyricist but the Brazilian military regime, which found his lyrics subversive, imprisoned and tortured him. The turning point in his life came when he later embarked on the five-hundred-mile pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. ‘At the end, I thought I would either forget my dream or write a book.’ That first book was the The Pilgrimage, a word-of-mouth success.

Coelho believes that the kind of dissatisfaction that can lead to adultery is a soul sickness. His protagonist, Linda, is a married woman whose restlessness finds its natural resting place in adultery. Linda lives and works in Geneva as a journalist, using the cover of her work to re-engage with the politician Jacob Konig, whom she kissed as a teenager. Although having the ‘perfect life’, Linda feels dissatisfied and suffers from an all-consuming angst that she cannot justify even to herself. She is compulsively drawn to see her wish to take a lover through to its possibly destructive end, engineering the adulterous moments, enjoying the thrill they give her. Eventually, repenting of this, she spends a weekend away, hang-gliding, with her husband and it is this existential experience that allows her to transcend her dilemmas. So, asks Coelho, why does Linda act as she does? And of course the answer – as any reader of his books knows – lies not directly within the apparent question, but in a ‘soul’ answer.

Linda is an unconvincing character who does not suffer any negative consequences from having committed adultery. There is a feeling that Coelho’s storyline is merely a backdrop for him to punctuate with his beliefs and the conclusions that he has reached about the meaning of life. Presumably his loyal readership will accept this narrative in order to connect with these beliefs, but for others, reading Adultery can be quite jarring.

An example of this comes when the author interrupts Linda’s first person narration, which drives the story, to speak in his authorial voice: ‘After three years of marriage, the person already knows what the other wants and thinks… Sex goes from being a passion to a duty… Women hang out and brag of their husbands’ insatiable fire, which is nothing but an outright lie. Everyone knows this but no one wants to be left behind.’ And later, towards the conclusion of the book, Coelho appears again, to say: ‘Those who know how to love Truth, rejoice with the truth, and do not fear it, because sooner or later it redeems everything. They seek the Truth with a clear, humble mind lacking prejudice or intolerance – and are ultimately satisfied with what they find.’

Reading Adultery reminded me of walking through a cold sea and occasionally finding warm patches. It is a moral tale but without the depth of a tale convinced about its own morality.