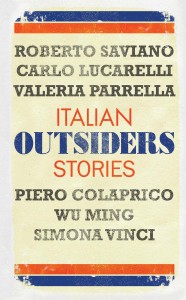

Outsiders

Translated by Ben Faccini

Published by Maclehose Press 28 February 2013

Roberto Saviano, Carlo Lucarelli, Valeria Parrella, Piero Colaprico, Wu Ming and Simona Vinci are six of Italy’s most innovative and successful contemporary writers. Saviano, for example, is the author of Gomorrah and Valeria Parrella won the Premio Campiello for best debut in 2004.

This new collection of stories highlights their work and is linked by common themes of belonging, dislocation and identity. Together they take the pulse of a country in turmoil.

Now sample writing from the Wu Ming Foundation – a collective of novelists and cultural activists whose slogan is “The Good Side of Italy” – for yourself.

*

London, 9 July, 1769

My Dear Friend,

It is with great Pleasure that I learn from your latest Letter that you are now enjoying full Health. I hope that this may continue, because even without immediately taking up again your long Journeyings, as of old, you may still be very useful to your Country and to Human Kind, if only you would sit down at your Desk to bring together the Knowledge you have acquired and publish the Observations you have made. It is true that many People hold Accounts of old Buildings and Monuments in high Esteem, but at the same Time there are a good Number who find the Kind of Information that you are now able to offer to be of great Interest. For example, I confess that if, during your Tour of Italy, you could find a Recipe for the making of Parmesan Cheese, it would be more pleasing to me than any Ancient Inscription.

Here in London recently, yet another Pamphlet has been published on the Degeneracy of the American Provinces. The Author repeats the habitual Fabrications about the Animal and Plant Life, but to these he adds a New Particular, maintaining that even the European Culinary Art imported into the Colonies is now become barely edible. I believe the Way of responding to this Provocation consists in reproducing in America the best of European Cooking Skills, introducing not only useful Plants and Animals but also the Traditional Knowledge required, which is not often found in Books, but in the Hands of Qualified Masters.

Further in this Matter, I pray you keep me informed of the Experiments of our Friend Dr Lynch, who as far as I know has not yet succeeded in curdling the Chinese Beans I sent him and producing the Tofu Cheese that I mentioned to you. And on the matter of Seeds, I would ask you to send me some Rare Examples, to the value of one Guinea, for which Mr Foxcroft will repay you on my Behalf: they are of particular Interest to a London Friend. If I may be of any Assistance to you from here, please do not hesitate to ask.

Your Affectionate Friend, Franklin

Reggio Emilia station. Location, the region of Reggio Emilia. Twenty minutes late on a forty-minute journey. I googled the map last night, the meeting’s on the outskirts, nevertheless I was counting getting there on foot, going across town to see if it really is Emilia’s most nondescript principal city.

In that moment, I have no doubts: the sky is a grubby ceiling that leaks water, it’s already nine and I’m forced to take a taxi.

‘Via Roosevelt, number 28,’ I tell the taxi driver as I sink back into the seat.

I take out my mobile to tell them I’ll only be a few minutes late, then realize I’ve no number to call, having forgotten to ask for it and, even if I did have it, I’d have forgotten to bring it. So I send Federica a text with kisses and a good morning, seeing as I left early, while she and Jacopo were still asleep.

It’s a Monday morning rush hour and raining. The traffic’s running slowly, the cars like cans of meat on a conveyor belt. I arrive at my destination in the same time that Google Maps said it would take to walk. Let’s say I did it so as not to get wet. A thirteen-euro luxury for which I would never be reimbursed.

The Professore’s given me the job, ‘the most able young researcher we have’, because an old friend of his is involved. Not enough of a friend to make him shift himself, though, it seems. As usual, he described the business to me in a hurried and absent-minded phone call. When I called him back later for more details, he told me that he knew little about it himself.

‘The consortium that protects Parmesan cheese needs a historian specialized in the American Revolution. It’s a legal matter.’

The head of the law firm handling the case is Ettore Melchiorri. He and the Professore are members of some Rotary Club or other. The appointment is for nine the next day in theconsortium’s central office.

‘I didn’t ask for the exact address, but it’s definitely in Parma. Someone like you who knows his way about the internet can find it in a couple of seconds.’

I did indeed carry out an online search and found that the consortium’s headquarters was in Reggio Emilia. And so here I find myself in a district that’s a mixture of small factories, shopping centres and blocks of flats. Telling one from another is a matter of reading the signs more than architecture.

I ring at number 28, go in and the girl at reception shakes my hand.

‘This way, Dottor Bonvicini, they’re waiting for you.’

She accompanies me, her heels sounding like rapid fire along the corridor’s gleaming tiles. The walls are hung with publicity posters and still lifes of cheese in pyramid formations.

The girl knocks at a door and politely introduces me. Inside, four men are sitting round a table drinking coffee. Dark or pinstriped suits, shirts white or blue. I thought I’d be the only one without a tie. But I only had one winter suit, tobacco brown, and that had been liberally sprayed with spumante afterthe last round of degree ceremonies. Strange to say, the more a Ph.D. degree loses its value, the more the relatives come armed with laurel wreaths and Asti Cinzano.

‘Please, take a seat, Dottor Bonvicini,’ says a youthful fifty something. He makes the introductions in so great a hurry I remember only that the guy on his right works like himself for the Consortium, while the two on the left – one about sixty, the other about my age – are Melchiorri, the head of the law firm, and his assistant.

‘Avvocato Melchiorri was just telling us that Professore Lolli speaks very highly of you, Dottor Bonvicini.’

I force a smile (what else are you supposed to do under these circumstances, say ‘thank you’?) and sit down with the day’s third cup of coffee. On a tray in the centre of the table are some inviting-looking chocolates, but when I bite into one I discover they are cubes of coated Parmesan (or perhaps I should say ‘in disguise’). It’s difficult to know if they’re a delicacy for connoisseurs or a cruel initiation rite. Everyone’s eyes are pinned on me. I take a deep breath and swallow, trying to forget the experience.

‘Well then, I suggest we make a start,’ the executive says, not wanting to waste any time. ‘You’re already wondering what this is about, aren’t you, Dottor Bonvicini? What has an American history scholar got to do with cheese?’

He continues to smile pleasantly. I nod back in silence. Indeed, Professore Lolli’s explanations have been far from clear.

I shoot a glance at Avvocato Melchiorri’s rather wizened features, but his gaze is still sharp. His young assistant sports an artificial suntan and a tie in a fat Windsor knot.

‘In the file we’ve prepared for you,’ ‘Mr Parmesan’ continues, ‘you’ll find documentation of a recent legal case in which historical archives have allowed us to make huge steps forward in protecting our product internationally.’

I realize only then that I have the classic rough-cloth shopping bag in front of me filled with tiny free gifts and publicity material. I untie a black binder stamped with the consortium’s logo and leaf through its wad of pages.

‘As you’ll be able to read, we’ve ordered Germany to stop the use of the designation “Parmesan” for marketing products that don’t have our certification. The Germans defended the use by saying that in their language the term’s considered generic, synonymous for any hard cheese. Avvocato Melchiorri consulted a philology expert to show that the general use of the term was very recent and had no historical foundation. Did you know that “Parmesan” even appears in Stevenson’s Treasure Island?’

He pauses indulgently until I gratify him with a shake of the head and then he continues.

‘One of the characters, Dr Livesey, keeps a piece in his snuffbox and since 1897 all German editions of the novel have called this little gem “Parmesan”. But for every one of those different editions, the expert pointed out German novels published in the same year where other hard cheeses for shaving or grating are mentioned and they never use that designation.’

He shows his yellow teeth again.

‘Would you ever have said that literature and history could be so important for the food industry?’

Perhaps he again expects me to shake my head. Instead, I reply: ‘Well, gastronomy is culture as well.’

He hides his amazement, before showing he’s happy with what I say.

‘Of course. And with these valid reasons, the firm of Melchiorri and partners won the case. The Germans cannot market their hard cheeses under the name of “Parmesan”.’

‘Mr Parmesan’ beams in the lawyers’ direction.

‘Please, avvocato, go ahead.’

Melchiorri exchanges a glance with his young assistant, who nods slightly and starts to hold forth. Odd this, I was ready to bet he’d never say a word.

‘Thanks. Unfortunately, the problem we have now doesn’t relate to Germany, but the United States. The legislation that governs European Union countries doesn’t apply in America. In the United States, there’s a variety of solid cheeses produced in Wisconsin or New York State that can be called “Parmesan”. However, now an American cheese manufacturer is claiming the right to use the Italian term Parmigiano Reggiano.’

He looks me in the eyes, as if to assure himself I’m paying attention and adopts a grave tone.

‘As you can imagine, the question is of the utmost importance. The fate of one of our most important national products is at stake.’

A newborn’s gurgle breaks out in the room. It’s my mobile. I retrieve it from the bottom of one of my pockets and frantically switch it off. I hear myself saying some stock phrase about how children will touch everything, when in fact it’s obvious that the ringtone in question came into being with adult assistance. In this case, seeing as my mother-in-law is barely able to send a text, there’s no doubt about the guilty party’s identity: Federica, mother of my little one, who keeps a very serious 1950s ringtone on her phone, but can’t resist the temptation of slipping our son’s gurgling into my own pockets.

‘They want to send me to New York,’ I moan two hours later on the telephone to Professore Lolli, my train having come to a halt among the piggeries between Rubiera and Modena.

He replies that this is excellent news, a professional opportunity, which is precisely why he suggested it to me.

‘So you knew?’

No, but he hoped they would, he says, because it would help someone like me, a nudge in the right direction, an incentive, something that would drag me out of the usual round of archives and libraries. How can you study the American Revolution and not want to go to America?

‘It’s not that, Professore. I’ve been to America. It’s . . . well,

you know, the baby and my partner . . .’