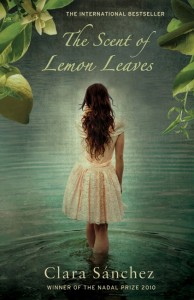

Published in paperback by Alma Books March 2013

Reviewed by Elizabeth Hilliard Selka

This slow-burning, award-winning thriller is ostensibly about Nazi-hunting on Spain’s southern coast, but in fact it concerns so much more. Solitude, friendship, loyalty, evil and goodness, courage and tenacity, motherhood, old age, the certainty of death… its themes lift it from being ‘merely’ a good read to a richly rewarding experience. And it’s warmly humourous too. It’s worth paying special attention in the first twenty pages because these are packed with important detail, you will realize later on; and for the same reason – that only later does it occur to you that such-and-such a detail that you glossed over the first time was significant after all – this novel rewards immediate re-reading. When you’ve finished, simply turn it over and start again.

Julián and Sandra are unlikely detectives. He’s an octegenarian Argentinian with a heart condition and troublesome contact lenses. She’s a thirtyish drifter casually made pregnant by an older colleague at a job she hated, now staying on the coast in her sister’s holiday cottage to give herself a break and try to get her life into focus. He has been drawn to the same spot by a letter from Salva, a friend he hasn’t seen for umpteen years. Julián and Salva were Spanish republicans sent in 1940 to Mauthausen concentration camp where they helped each other survive. After the war, Julián married Raquel, another inmate, and moved to South America. Salva embarked on a lifetime’s work hunting Nazis through the Memory and Action Centre. Julián arrives to find that Salva has died, but decides to stay anyway since he’s come all this way, and pursue the Norwegian couple a photograph of whom Salva had sent him. It happens that these elderly people have just befriended Sandra at the beach and invited her into their home. Thus the scene is set for a tale of conspiracy and adventure with deadly undertones, and that even before Sandra and Julián meet, which happens some fifty pages into the story.

Sánchez knows how to keep up the tension. She takes her time dropping new elements into the mix, small facts which Julián or Sandra discover in the course of their adventure which alter the complexion of the investigation and contribute to the bigger picture. This is drama by stealth, reeling you in as surely and subtly as the two friends are irrevocably drawn to secrets. Sánchez’s storytelling is masterly and she deserves to be better known in the English-speaking world. In this psychological thriller we can’t be sure who will survive or how. Julián himself does not believe that his actions will result in the Nazis whom he tracks down, however well-known they are for however terrible crimes, being brought to justice in the conventional sense of court trials and prison. So what form will justice take? The tone of this novel, and the physical weakness of all the main protagonists, suggest it will not be some sort of shoot-out or blood-bath. And indeed, much more subtle and poetic forms of retribution and resolution await all the characters.

This novel proves that it is possible for a story about some of mankind’s most notorious monsters to bring smiles to the face of the reader, though there is sadness too, as well as moments of horror. Sandra and Julián are much cleverer and more enterprising than they think themselves at the beginning of the story; by the end they are also much wiser.

There are still a few glitches in the translation. In a downpour Sandra takes shelter in a garden ‘pergola’, which since this is a roofless construction of pillars and beams designed to support climbing plants, would hardly keep her dry. The phrase ‘better said’ recurs – whereas in English this should be simply ‘rather’ (and indeed editors have made this correction intermittently). Elsewhere Sandra refers to a ‘blooper’ which is pure American but spellings such as ‘colour’ and the use of ‘chemist’ rather than ‘pharmacy’ demonstrate this is intended to be British English. Sandra’s social background seems confused by her use of ‘serviette’ in one place but ‘loo’ in another, though later she refers to ‘toilets’ so perhaps that settles it. But the most annoying detail is repeated use of ‘motorbike’ when Sandra specifies that what she rides is a Vespino, a 50cc bike with pedals, in other words a moped. None of these solecisms is perhaps important in itself; cumulatively they grate somewhat, but not on reflection enough to spoil the terrific read that is The Scent of Lemon Leaves.